Abstract

Dietary intake of long-chain n-3 PUFA is now widely advised for public health and in medical practice. However, PUFA are highly prone to oxidation, producing potentially deleterious 4-hydroxy-2-alkenals. Even so, the impact of consuming oxidized n-3 PUFA on metabolic oxidative stress and inflammation is poorly described. We therefore studied such effects and hypothesized the involvement of the intestinal absorption of 4-hydroxy-2-hexenal (4-HHE), an oxidized n-3 PUFA end-product. In vivo, four groups of mice were fed for 8 weeks high-fat diets containing moderately oxidized or unoxidized n-3 PUFA. Other mice were orally administered 4-HHE and euthanized postprandially versus baseline mice. In vitro, human intestinal Caco-2/TC7 cells were incubated with 4-hydroxy-2-alkenals. Oxidized diets increased 4-HHE plasma levels in mice (up to 5-fold, P < 0.01) compared with unoxidized diets. Oxidized diets enhanced plasma inflammatory markers and activation of nuclear factor kappaB (NF-κB) in the small intestine along with decreasing Paneth cell number (up to −19% in the duodenum). Both in vivo and in vitro, intestinal absorption of 4-HHE was associated with formation of 4-HHE-protein adducts and increased expression of glutathione peroxidase 2 (GPx2) and glucose-regulated protein 78 (GRP78). Consumption of oxidized n-3 PUFA results in 4-HHE accumulation in blood after its intestinal absorption and triggers oxidative stress and inflammation in the upper intestine.

Keywords: nutrition, polyunsaturated fatty acids, lipid peroxidation, 4-hydroxy-2-alkenals, intestine

Chronic inflammation and oxidative stress are now recognized as major factors involved in the pathogenesis of several current diseases, such as overweight, obesity, and cardiovascular diseases (1–3). Elevated levels of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines, such as interleukins (IL) and monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1), are hallmarks of the metabolic syndrome (1, 2). Several studies demonstrate the nutritional benefits of consuming long-chain (LC) n-3 PUFA from fish, in particular, docosahexaenoic acid (DHA, 22:6 n-3) and eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA, 20:5 n-3) to protect against several pathologies (4–7). Therefore, nutritional recommendations in Western societies have been established for n-3 PUFA intake of 500 mg/day of EPA and DHA to achieve nutrient adequacy, lower n-6/n-3 ratio and reduce incidence of chronic diseases, particularly cardiovascular diseases (8).

However, current studies reveal that the n-3 PUFA may not be devoid of risk. Possible harmful effects of high levels of n-3 PUFA on retinal membrane degeneration have been described by Tanito et al. (9). Dietary LC n-3 PUFA are highly vulnerable to oxidation, which is one of the major problems in food chemistry and may decrease their nutritional value. Indeed, peroxidation causes loss of nutritional quality and further leads to the generation of genotoxic and cytotoxic compounds, such as the 4-hydroxy-2-alkenals (10, 11). 4-Hydroxy-2-hexenal (4-HHE) and 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal (4-HNE) are major end-products derived from n-3 and n-6 PUFA peroxidation, respectively. In addition to being markers of lipid peroxidation in vivo, 4-HNE and 4-HHE induce noxious effects on biological systems. These lipid aldehydes are prone to react with thiol and amine moieties and produce Schiff base and/or Michael adducts with biomolecules, such as proteins, DNA, and phospholipids (12, 13). Numerous studies reported the genotoxicity and cytotoxicity of these 4-hydroxy-2-alkenals on tissues and cells in pathophysiological contexts (14–16), but nothing is known to date about the possible contribution of 4-hydroxy-2-alkenals present in food products, their fate after ingestion, and their metabolic effects.

In this context, the intestinal tract represents the first barrier of detoxification and defense against oxidative stress. Thus, intestinal cells can be exposed to oxidized PUFA or to lipid peroxidation end-products. However, evidence is lacking to support unfavorable health effects of dietary oxidized n-3 PUFA and to demonstrate their possible role in the generation of oxidative stress and inflammation. Furthermore, limited data are available to support the hidden assumption of intestinal absorption of dietary lipid oxidation by-products.

Therefore, we hypothesized that long-term intake of limited amounts of oxidized n-3 PUFA in high-fat (HF) diets could exert harmful health effects due to the absorption of their end-products such as 4-HHE by the small intestine, the end-products having been formed during the processing, storage, and/or final handling of foods or after their ingestion. The aim of the present study was thus to investigate i) the effects of oxidized n-3 PUFA diets compared with unoxidized diets on oxidative stress and inflammation in mice and ii) the possible implication of the intestinal absorption of some PUFA oxidation end-products, namely, 4-hydroxy-2-alkenals, through their effects on intestinal stress and inflammation in vivo and in vitro. Because several types of LC n-3 PUFA sources are present in human food, we tested lipid mixtures containing EPA and DHA carried by either triacylglycerols (TG) or phospholipids (PL). Moreover, we analyzed different segments of the absorptive intestinal epithelium, especially the duodenum before interactions with bile salts occur, the jejunum that represents the major site of lipid absorption, as well as the ileum to test whether some effects remain in this more distal segment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

4-HHE, 4-HNE, and trideuterated compounds were synthesized according to Soulère et al. (17). Omegavie® Tuna oil 25 DHA-flavorless as a source of triacylglycerol rich in long-chain n-3 fatty acids (TG-DHA, 26% of DHA), lecithin rich in DHA (PL-DHA, 41% of DHA), and kiwi seed oil were provided by Polaris (Pleuven, France). Lard was supplied by Celys (Rezé, France), sunflower oil was from Lesieur® (Asnières-sur-Seine, France), and oleic sunflower oil from Olvéa (Marseille, France). Vegetable lecithin rich in linoleic acid 18:2 n-6 (PL-LA) was from Lipoid (Frigenstrasse, Germany).

Preparation of unoxidized and oxidized lipid blends and mice diets

Four lipid blends were prepared at the labscale to obtain similar fatty acid composition and quantities in the four diets and similar amounts of phospholipids and triacylglyerols. In these blends, DHA was supplied either in the form of triacylglycerols (TG diet) or phospholipids (PL diet); i.e., the name chosen for the diets reflects the type of molecules that carry long-chain n-3 PUFA in the diet. The oxidized lipid blends (TG-ox and PL-ox, respectively) were prepared as follows. Primary lipid mixtures for PL and TG groups were prepared with a small proportion of lard to maintain oxidability of PUFA. These preliminary oil mixtures were dispersed in aqueous phase (mineral water; Evian) to prepare 30% w/w oil-in-water emulsions. The emulsions were then kept at 50°C in the dark with continuous shaking until the oxidation level was considered sufficient according to our previous experiments (estimated α-tocopherol contents of the blends decreased by 50%). Oxidized emulsions were then lyophilized, and the resulting oxidized lipid mixtures completed with the necessary quantity of lard to reach the required final composition of lipid blends. The composition of the four diets is reported in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Composition of diets containing long-chain n-3 PUFA either esterified in phospholipids (PL diet) or in triacylglycerols (TG diet) and their oxidized counterparts (PL-ox, TG-ox)

| High-fat containing n-3 PUFA as | PL | PL-ox | TG | TG-ox |

| Ingredient (g/100g) | ||||

| Lipid mixture, among which are | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 |

| Lard | 18.10 | 18.10 | 18.06 | 18.06 |

| Sunflower oil | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.2 | 0.2 |

| Oleic sunflower | 0.4 | 0.4 | — | — |

| Kiwi seed oil | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.02 | 0.02 |

| Tuna oil (DHA located in TG) | — | — | 0.9 | 0.9 |

| Phospholipids, among which are | ||||

| PL-DHA (DHA located in PL) | 0.8 | 0.8 | — | — |

| Lecithin PL-LA | — | — | 0.8 | 0.8 |

| Corn starch | 39 | 39 | 39 | 39 |

| Sucrose | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| Pure cellulose | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| Vitamin mixture | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| Mineral mixture | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Tocopherolsa | 0.099 | 0.099 | 0.092 | 0.084 |

| Energy content (kJ/g) | 18.14 | 18.14 | 18.14 | 18.14 |

| Energy % | ||||

| Lipids | 41.5 | 41.5 | 41.5 | 41.5 |

| Protein | 15.7 | 15.7 | 15.7 | 15.7 |

| Carbohydrates | 34.1 | 34.1 | 34.1 | 34.1 |

Considering the difference observed in tocopherols in lipid mixtures, which can affect their metabolic impact (46), care was taken to supplement lipid mixtures with α-tocopherol during formulation to achieve iso-tocopherol diets.

Animals and diets

Male C57BL/6 mice (8 wk, 20g) were from Janvier SA (Le Genest Saint-Isle, France) and were housed in a temperature-controlled room (22°C) with a 12 h light/12 h dark cycles. After 2 weeks of chow diet, mice were randomly divided into four groups of 12 mice and fed one of the 4 high-fat diets containing n-3 PUFAs: unoxidized groups: PL, TG; oxidized groups: PL-ox, TG-ox. Animal experiments were performed under the authorization n°69-266-0501 (Direction Départementale des Services Vétérinaires du Rhône). All experiments were carried out according to the guidelines laid down by the French Ministry of Agriculture (n° 87-848) and the E.U. Council Directive for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of November 24th, 1986 (86/609/EEC), in conformity with the Public Health Service (PHS) Policy on Humane Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. COS holds a special license (n° 69266257) to experiment on living vertebrates issued by the French Ministry of Agriculture and Veterinary Service Department. Body weight was measured twice weekly and food intake was measured weekly. After 8 weeks, mice were euthanized by intraperitoneal (IP) injection of sodium pentobarbital (60 mg/kg). Plasma, liver, white adipose tissue (epididymal, retroperitoneal, subcutaneous) and small intestine mucosa were collected.

Caco-2/TC7 cell culture and treatment

Caco-2/TC7 cells, which are the widely used in vitro model of human origin to test intestinal absorption of lipids, were provided by Monique Rousset (Centre de Recherche des Cordeliers, Paris, France) and used between passages 35 and 45. Cells were seeded in 75 cm2 flasks (Falcon; Becton Dickinson) until 80–90% confluence. They were grown in complete DMEM (Gibco) supplemented with 20% heat-inactivated FBS (Gibco), 1% nonessential amino acids (Gibco), and 1% antibiotics (penicillin/streptomycin; Gibco) and then maintained under a 10% CO2 atmosphere at 37°C. For experiments, cells were seeded at a density of 25 × 104 cells per filter on microporous (0.4 μm pore size) polyester filters (Transwell; Corning, USA) and grown to confluence in complete medium, which was routinely reached 7 days after seeding. The cells were used 21 days after seeding. Monolayers were incubated with 4-HHE or 4-HNE in the apical compartment (1–100 µM brought in DMSO at 0.5% in the final medium), and the basolateral compartment received serum-free DMEM. After incubation, basolateral media and cells were collected.

Animal treatment with 4-HHE

After an overnight fast, three groups of four male C57/BL6 mice (8 weeks old, 22 g) were given a single application of 4-HHE diluted in water via 0.5% DMSO by oral gavage at a dosage of 10 mg/kg body weight and then were euthanized 1, 2, and 4 h after gavage. A fourth group of mice was euthanized immediately after gavage for the baseline control. For euthanizing, mice were anesthetized by IP injection of pentobarbital (35 mg/kg), and blood was collected by cardiac puncture with heparinized syringes. Plasma and small intestine mucosa (duodenum and jejunum) were collected.

4-Hydroxy-2-alkenals: derivatization, analysis, and quantification

4-hydroxy-2-alkenals were derivatized from 400 µl of basolateral media of Caco-2/TC7 or from 300 µl of plasma, under argon, and in lipid blends as described previously (18). Deuterated 4-HNE and 4-HHE (20 ng), used as internal standards, were added to the samples. Briefly, they were treated with O-2,3,4,5,6-pentafluorobenzyl hydroxylamine hydrochloride. After acidification with H2SO4, pentafluorobenzyloxime derivatives were extracted with methanol and hexane. The hydroxyl group was then converted into trimethylsilylether after an overnight treatment with N,O-bis(trimethylsilyl)trifluoroacetamide at room temperature. The pentafluorobenzyloxime trimethylsilylether derivatives of 4-HHE (O-PFB-TMS-4-HHE) and 4-HNE (O-PFB-TMS-4-HNE) were then analyzed by GC-MS using negative ion chemical ionization (NICI) mode on a Hewlett-Packard quadripole mass spectrometer interfaced (18) with a Hewlett-Packard gas chromatograph (Les Ullis, France).

IL-6 and MCP-1 measurements

IL-6 and MCP-1 (Clinisciences, Nanterre, France) were assayed by ELISA kit according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Plasma triacylglycerols and NEFA measurements

Plasma triacyglycerols (TAG) were measured with the triglyceride PAP kit (BioMérieux, Marcy l'Etoile, France) as previously described (19). Plasma TAG concentration was calculated by subtracting the free glycerol in plasma measured with the glycerol UV-method (R-Biopharm/Boehringer, Mannheim, Germany). Plasma NEFA was measured using NEFA-C kit (Wako Chemicals, Neuss, Germany) (19).

Fatty acid analysis

Total lipids were extracted from 35 µl of plasma as described previously (19). The organic phase was evaporated under N2, and total fatty acids were transesterified using boron trifluoride in methanol (BF3/methanol) (19). The FA methyl esters were then analyzed by GC using a DELSI instrument model DI 200 equipped with a fused silica capillary SP-2380 column (60 m × 0.22 mm). Heptadecanoic acid (C17:0; Sigma, France) was used as an internal standard.

Quantification of free malondialdehyde and hydroperoxides in oil mixtures

Thiobarbituric acid-malondialdehyde (MDA) adducts were separated using a method adapted from different authors (20, 21) by HPLC and measured by fluorimetry using an external calibration curve (excitation 535 nm, emission 555 nm). Hydroperoxides were quantified in lipid blends according to a method adapted from Nourooz-Zahed et al. (22).

Quantitative PCR analysis

Total RNA was extracted from Caco-2/TC7, duodenum, jejunum, and ileum of mice using the NucleoSpin® RNA/Protein kit (Macherey Nagel, Duren, Germany). cDNAs were synthesized from 1 µg of total RNA in the presence of 100 units of Superscript II (Invitrogen) with a mixture of random hexamers and oligo (dt) primers (Promega, Charbonnières, France). The amount of target mRNAs was measured by RT, followed by real-time PCR, using a Rotor-Gene Q (Qiagen, France). Primer sequence and RT-quantitative PCR conditions are available upon request (cyrille.debard@univ-lyon1.fr). Hypoxanthine guanine phosphoribosyl transferase (HPRT) mRNA level and TATA-box binding protein (TBP) mRNA were used to normalize data of duodenum, jejunum, ileum, and Caco-2/TC7 cells, respectively.

Western blot analysis

Total proteins from Caco-2/TC7 and jejunum of mice were extracted with the NucleoSpin® RNA/Protein kit (Macherey Nagel). A total of 40 μg of protein from each sample were subjected to 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred to a polyvinylidine fluoride (PVDF) membrane. Membranes were blocked with kit reagent and incubated overnight with antibodies according to the manufacturer's recommendations. Antibodies against total NF-κB P65 and phospho-NF-κB P65 (Ser 529) were obtained from Signalways Antibody (Clinisciences, France); phospho-IκBα (phosphoS32+S36) was from Abcam (Cambridge, UK); and β-actine was from Sigma, France. After incubation with secondary antibody, blots were developed with a commercial kit (WesternBreeze Chemiluminescent, Invitrogen, France). Quantification was performed by densitometry analysis of specific bands on immunoblots with Quantity One software (Bio-Rad, Marne-la-Coquette, France).

Immunohistochemistry

Duodenal tissues were removed, fixed in 90% ethanol for 24 h at −20°C, and processed into paraffin. Serial paraffin sections (4 µm) were rehydrated, and endogenous peroxidase activity was quenched with 20 min incubation in 5% H2O2/PBS. After incubation in 2.5% normal horse blocking serum (Impress, Vector), sections were incubated for 60 min at room temperature with anti-lysozyme (1/100; Zymed Laboratories) antibody diluted in blocking solution. The immune reactions were then detected by incubation with a ready-to-use peroxidase-labeled secondary reagent, ImmPRESS (MP-7401 for rabbit antibodies; Abcys, Paris, France) (30 min, room temperature). Control experiments were performed simultaneously omitting the primary antibody or incubating with preimmune rabbit serum. The sections were then counterstained and mounted.

Quantitative analysis for Paneth cells

The Paneth cell lineage was analyzed by assessing the percentage of crypt cross-sections with Paneth cells (per 80 crypts). For this purpose, four to six sections were analyzed per mouse. A crypt was considered when it was cut along or nearly along the length of the crypt lumen (at least two thirds of the length of the crypt). All slides were analyzed by a single investigator who was blinded to the treatment groups.

Protein carbonyl content

Protein carbonyl content was determined with an Oxyblot Oxidized Protein Detection Kit from Chemicon (Hampshire, UK). The carbonyl groups in the protein chains were derivatized into dinitro-phenyl-hydrazone by reaction with dinitro-phenyl-hydrazine (DNPH) according to the manufacturer's instructions. After the derivatization of the protein sample (20 µg), one-dimensional electrophoresis was carried out on a 10% SDS-PAGE gel, and proteins were transferred to PVDF membranes. After incubation with anti-DNP antibody, the blot was developed with a chemiluminescence detection system. The intensity of each line was measured and normalized by mean control levels.

Dot blot analysis

Fifty milligrams of total proteins from Caco-2/TC7 cells or from duodenum and jejunum of mice were spotted onto nitrocellulose membrane. Blocked membrane was incubated overnight with anti-HNE-adducts (Calbiochem 393207, San Diego, CA, USA) or anti-HHE-adducts (CosmoBio N213730-EX, Tokyo, Japan) antibodies. Blots were developed with a commercial kit (WesternBreeze Chemiluminescent, Invitrogen, France). The quantification was performed by densitometric analysis of specific spots on immunoblots using Quantity One software.

Statistical analysis

All data are presented as means ± SEM and were analyzed using Statview 5.0 software (Abacus Concept, Berkeley, CA). One-way ANOVA followed by Fisher PLSD was used for i) the dietary study to compare PL, PL-ox, TG, and TG-ox groups, ii) the gavage study to compare plasma alkenal concentrations as a function of time, and iii) the Caco-2 cell studies to compare treatment effects. Two-way ANOVA followed by Fisher PLSD was used to compare oxidized versus unoxidized groups globally in the dietary study (mice of oxidized groups versus mice of unoxidized groups). Differences were considered significant at the P < 0.05 level.

RESULTS

Diet compositions and biometric data

Table 2 shows that we succeeded in producing lipid mixtures containing different amounts of oxidation products, especially 4-HHE, which was significantly higher in oxidized versus unoxidized lipid blends. MDA and hydroperoxides in oxidized oils were in a range considered as acceptable for human consumption. Noticeably, oxidation did not impact the fatty acid profile (Table 2); n-3 PUFA content and n-6/n-3 ratio were consistent with dietary recommendations. Mice in oxidized and unoxidized groups did not differ in final body weight gain, liver weight, white adipose tissue, plasma TAG, or plasma NEFA (Table 3).

TABLE 2.

Fatty acid composition and oxidation markers in the lipid blends

| PL | PL-ox | TG | TG-ox | |

| FA (mg/g lipid) | ||||

| SFA | 319 ± 12 | 319 ± 9 | 293 ± 19 | 319 ± 23 |

| MUFA | 410 ± 13 | 413 ± 7 | 375 ± 17 | 372 ± 23 |

| n-6 PUFA | 105 ± 3 | 106 ± 1 | 104 ± 11 | 112 ± 11 |

| n-3 PUFA, among which are | 18.1 ± 0.4a | 17.9 ± 0.1a | 22.2 ± 2.8b | 23.4 ± 2.7b |

| 18:3 n-3 | 10.6 ± 0.3 | 10.7 ± 0.1 | 9.4 ± 0.9 | 10.0 ± 1.3 |

| 20:5 n-3 | 0.9 ± 0.3a | 1.1 ± 0.0a | 2.2 ± 0.3b | 2.4 ± 0.2b |

| 22:6 n-3 | 4.3 ± 0.0a | 3.9 ± 0.0a | 8.8 ± 1.9b | 8.8 ± 0.9b |

| Total PUFA | 123 ± 4 | 124 ± 1 | 126 ± 10 | 136 ± 13 |

| n-6/n-3 ratio | 7.7 ± 0.5b | 7.4 ± 0.1b | 5.4 ± 0.2a | 5.5 ± 0.1a |

| Total FA | 849 ± 129 | 853 ± 16 | 790 ± 18 | 820 ± 48 |

| Lipid peroxidation markers (nmol/g of lipid blend) | ||||

| 4-HHE (oxidation of n-3) | 0.5 ± 0.1a | 1.2 ± 0.2b | 1.9 ± 0.1c | 8.5 ± 0.5d |

| 4-HNE (oxidation of n-6) | 0.2 ± 0.1a | 0.5 ± 0.1a | 1.7 ± 0.2b | 4.4 ± 0.5c |

| MDA | 25 ± 2.5a | 40.0 ± 4.0a | 5.9 ± 1.2b | 35 ± 14a |

| Hydroperoxides (µmol eq. H2O2/g lipid) | 1.6 ± 0.9a | 1.3 ± 0.1a | 3.7 ± 0.1b | 5.8 ± 0.1c |

Means in a row superscripted by different letters are significantly different (P < 0.05). Data are means ± SEM for n = 3. FA, fatty acid; MDA, malondialdehyde; MUFA, monounsaturated fatty acid; SFA, saturated fatty acid.

TABLE 3.

Morphologic parameters, food intake, and plasma lipid concentrations of mice fed oxidized (PL-ox, TG-ox) or unoxidized (PL, TG) n-3 diets

| Mice Groups According to Dietary Lipids | ||||

| Morphologic Parameters | PL | PL-ox | TG | TG-ox |

| Biometric data | ||||

| Initial body weight (g) | 23.9 ± 0.3 | 24.0 ± 0.3 | 24.5 ± 0.3 | 24.1 ± 0.3 |

| Body weight gain (g) | 3.1 ± 0.1 | 4.3 ± 0.5 | 3.7 ± 0.3 | 3.0 ± 0.5 |

| Energy intake (kJ/mouse/d) | 60.2 ± 1.3 | 62.7 ± 0.3 | 59.8 ± 1.3 | 68.1 ± 1.3 a |

| Liver weight (g) | 1.21 ± 0.04 | 1.24 ± 0.06 | 1.27 ± 0.04 | 1.28 ± 0.05 |

| WAT weight (g) | 0.72 ± 0.05 | 0.95 ± 0.10 | 0.93 ± 0.11 | 0.73 ± 0.05 |

| Plasma lipids | ||||

| Triglycerides (mM) | 0.64 ± 0.04 | 0.64 ± 0.10 | 0.57 ± 0.04 | 0.58 ± 0.04 |

| NEFA (mM) | 0.27 ± 0.01 | 0.32 ± 0.02 | 0.37 ± 0.02 | 0.28 ± 0.01 |

Data are means ± SEM for n = 7–9 per group. WAT, white adipose tissue.

P < 0.05, ANOVA followed by Fisher test for TG-ox versus TG.

Aldehyde stress and inflammatory markers in plasma of mice fed oxidized n-3 diets

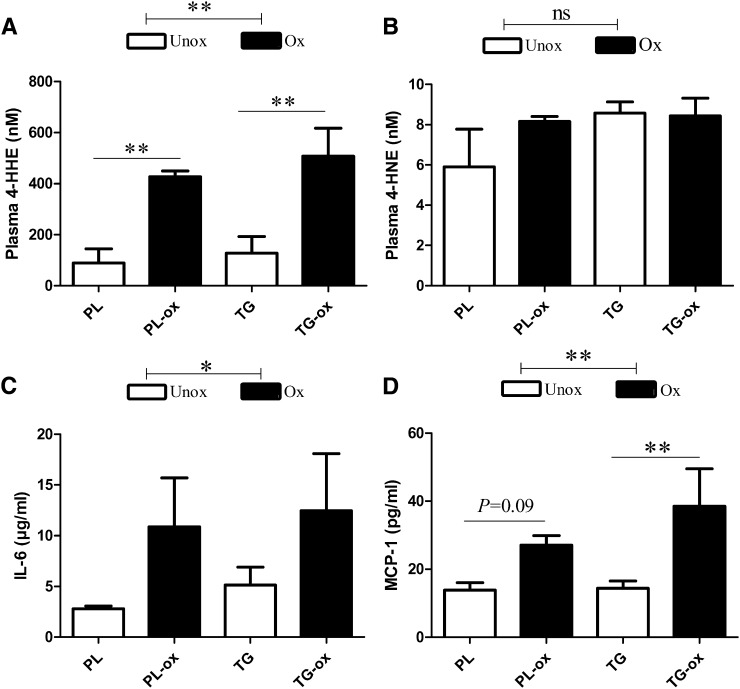

Because consuming oxidized n-3 diets could contribute to circulating biomarkers of lipid peroxidation such as 4-HHE and 4-HNE, we measured these 4-hydroxy-2-alkenals in plasma. Fig. 1A shows a 4-fold increase of 4-HHE concentration in the plasma of oxidized groups (427–508 nM) versus unoxidized groups (89–128 nM) (P < 0.01). However, the concentration of 4-HNE (from n-6 PUFA) did not differ among groups (from 6 to 9 nM; Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

4-HHE (A) and 4-HNE (B) concentrations and inflammatory markers IL-6 (C) and MCP-1 (D), in plasma of mice fed oxidized or unoxidized n-3 diets. Bars represent means ± SEM of n = 3 pools of three mice for 4-HHE and 4-HNE or n = 6–8 for inflammatory markers. **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05. ANOVA followed by Fisher test.

FA composition of total plasma lipids was characterized to test whether chronic ingestion of oxidized diet would affect PUFA metabolism. Plasma FA profile (see supplementary Table I) actually reflected the composition of ingested dietary fats. The proportions of n-3 PUFA (EPA, DHA, α-linolenic acid) and n-6 PUFA (arachidonic acid, 20:4 n-6; linoleic acid, 18:2 n-6) were similar in plasma of each oxidized and corresponding unoxidized groups.

Regarding metabolic inflammation, there were higher concentrations in plasma of the proinflammatory cytokine IL-6 (Fig. 1C) and the chemokine MCP-1 (Fig. 1D) in oxidized groups.

Altogether, high-fat diets containing realistically oxidized n-3 PUFA induced the highest amounts of 4-HHE and inflammatory markers in plasma. We therefore questioned whether oxidized oils would affect the small intestine, which is the primary defense line of the host regarding ingested products.

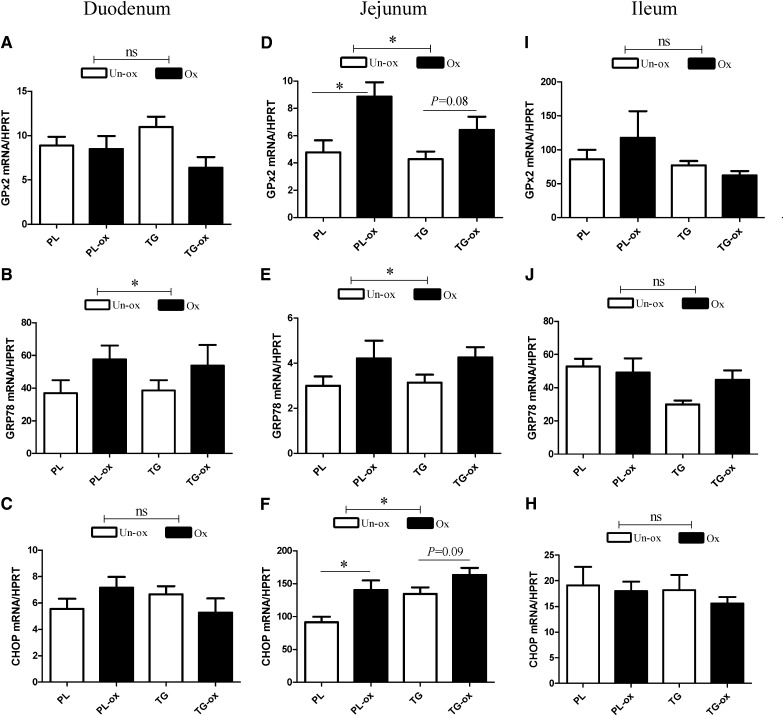

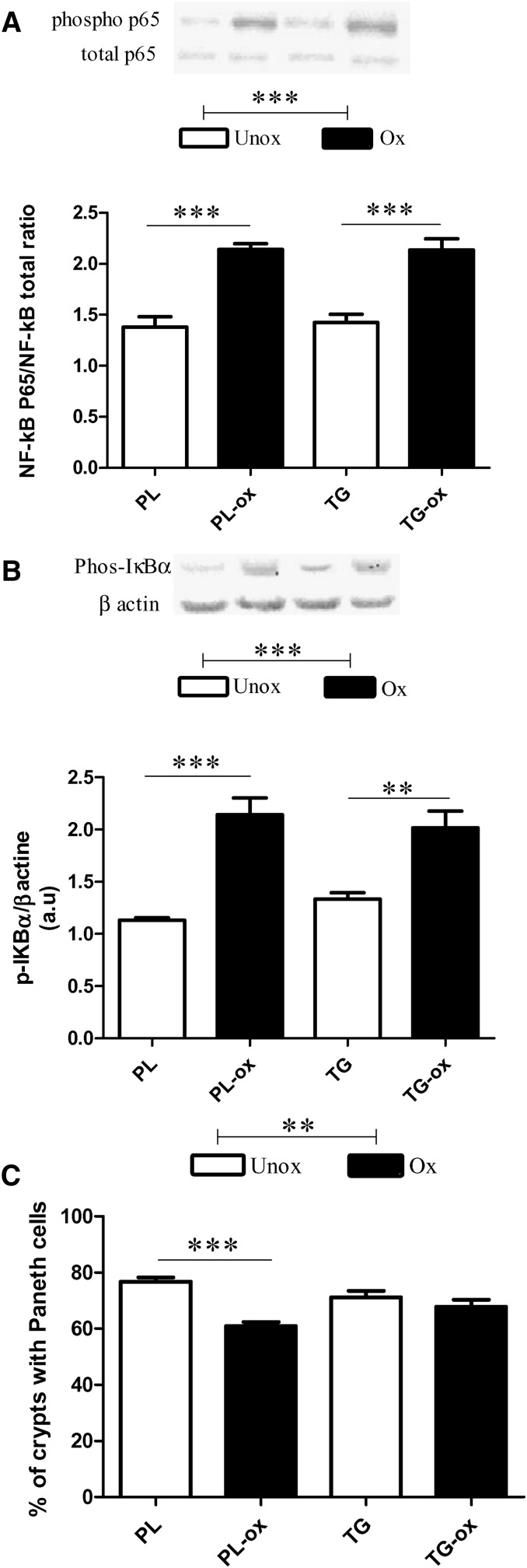

Effects of oxidized diets on markers of stress and inflammation in the small intestine

We analyzed the small intestine mucosa regarding the expression of genes known to be specifically involved in cell defense against oxidative stress and detoxification. The expression of GPx2, a gastrointestinal glutathione peroxidase mainly expressed in the intestine, was increased specifically in the jejunum of oxidized groups (Fig. 2D; P < 0.05). Moreover, we examined the gene expression of two markers that are linked to endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress. Mice fed oxidized diets exhibited a significantly higher expression of prosurvival factor glucose-regulated protein 78 (GRP78), both in the duodenum and in the jejunum (Fig. 2B, E; P < 0.05). The proapoptotic C/EBP homologous protein (CHOP) was significantly higher in the jejunum of oxidized groups (Fig. 2F). However, on the whole, no effects of n-3 PUFA oxidation were observed in the ileum. Regarding inflammation, results show that the jejunum of mice fed oxidized diet exhibited an increased phosphorylation of NF-κB P65 (Fig. 3A; P < 0.0001), a major transcription factor involved in inflammation, that was associated with a significant increase of phosphorylated IkappaB α (IκBα), an inhibitor NF-κB protein (Fig. 3B; P < 0.0001). The activation of NF-κB requires the phosphorylation and degradation of the IκB protein that prevents the nuclear translocation of active NF-κB. We also analyzed Paneth cells in the duodenum, which are involved in innate immunity by sensing bacteria and by discharging antimicrobial peptides including α-defensins. Paneth cell number was significantly decreased after oxidized versus unoxidized diets (Fig. 3C). Moreover, the gene expression of lysozyme 1 (Lyz-1) produced by Paneth cells was decreased in the duodenum in the PL-ox group compared with the PL group (93 ± 20 versus 315 ± 161; values normalized to the levels of HPRT mRNA); no differences were observed lower in the intestine in the jejunum (15–17 ± 2 mRNA/HPRT regardless of oxidation) nor in the ileum (∼250 ± 100 mRNA/HPRT regardless of oxidation).

Fig. 2.

Gene expression of GPx2, GRP78, and CHOP in the small intestine of mice fed oxidized or unoxidized n-3 PUFA diets in duodenum GPx2 (A), GRP78 (B), and CHOP (C); in jejunum, GPx2 (D), GRP78 (E), and CHOP (F); and in ileum GPx2 (I), GRP78 (J), and CHOP (H). This analysis was quantified by qPCR. Values are normalized to the levels of HPRT mRNA. Bars represents means ± SEM of n = 5–7 mice. * P < 0.05. ANOVA followed by Fisher test.

Fig. 3.

Effects of oxidized n-3 diets on the small intestine of mice after 8 weeks of diet. Phosphorylation status of NF-kB p65 (A) and phosphorylation of IκBα (B) in the jejunum by Western blotting, and Paneth cell number (C) in the duodenum measured by immunohistochemistry. Bars represent means ± SEM of n = 5–6 mice. **P < 0.001, ***P < 0.0001. ANOVA followed by Fisher test.

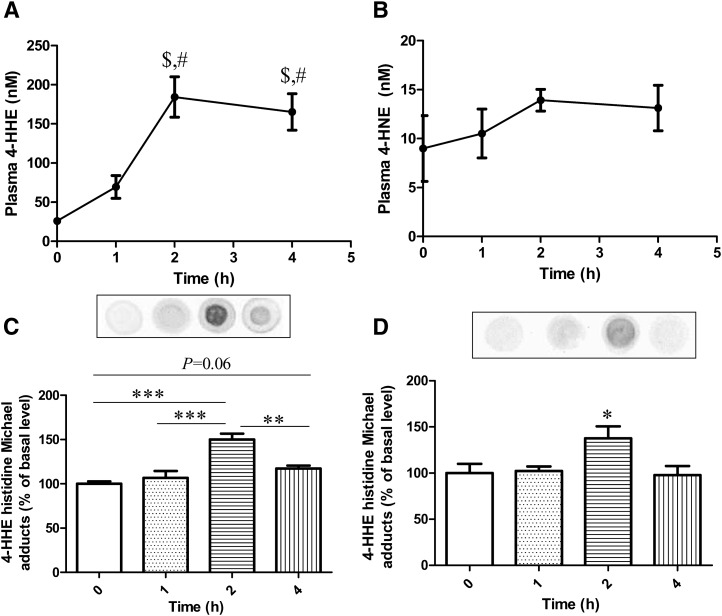

Kinetics of intestinal absorption of 4-HHE in mice and protein modifications in the small intestine

To test the hypothesis that the increased plasma level of 4-HHE following consumption of oxidized diet could be partly explained by the absorption of 4-HHE in the small intestine, we measured the levels of 4-HHE in the plasma of fasted mice after gavage with 4-HHE. Fig. 4A shows that 4-HHE intragastrically fed to mice at 88 µmol/kg body weight was partly absorbed after 1 h. Peak plasma concentration of 184 nM was reached 2 h after treatment (P < 0.001 versus baseline), corresponding to ∼0.1% of the fed dose. Importantly, no concomitant differences were observed in the plasma levels of 4-HNE (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

4. Plasma concentration of 4-HHE (A) and 4-HNE (B) and 4-HHE-protein adducts in the duodenum (C) and in the jejunum (D) in mice after oral administration of 10 mg/kg b.w. of 4-HHE. Bars represent means ± SEM of n = 4. $P < 0.001 versus baseline (0), #P < 0.01 versus 1 h. ***P < 0.0001, **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05. Repeated measures ANOVA followed by Fisher test.

We further tested the formation of Michael adducts of proteins in the duodenum and jejunum. As shown in Fig. 4C and D, there were significant increases of 4-HHE protein adducts that peaked at 2 h postgavage both in the duodenum (P < 0.001 versus baseline) and in the jejunum (P < 0.05 versus baseline). The observed decrease in adduction at 4 h reveals the capacity of intestinal mucosa to cope with carbonyl stress. We also observed an activation of GPx2 mRNA in the duodenum 4 h after gavage with 4-HHE: 80 ± 32 versus 38 ± 12 at baseline (mRNA/HPRT, P = 0.013); this effect was no longer observed in the jejunum (10 ± 3 at 4 h versus 9 ± 6 at baseline).

Absorption of 4-hydroxy-2-alkenals in vitro by Caco-2/TC7 cells

To further evaluate the capacity of enterocytes to absorb 4-hydroxy-2-alkenals, we incubated Caco-2/TC7 cells for 24 h with increasing concentrations of 4-HHE or 4-HNE. 4-Hydroxy-2-alkenals were devoid of cytotoxic effects as checked by the absence of leakage of lactate dehydrogenase and did not alter transepithelial electrical resistance (TEER), meaning that cell monolayer maintained its integrity (data not shown).

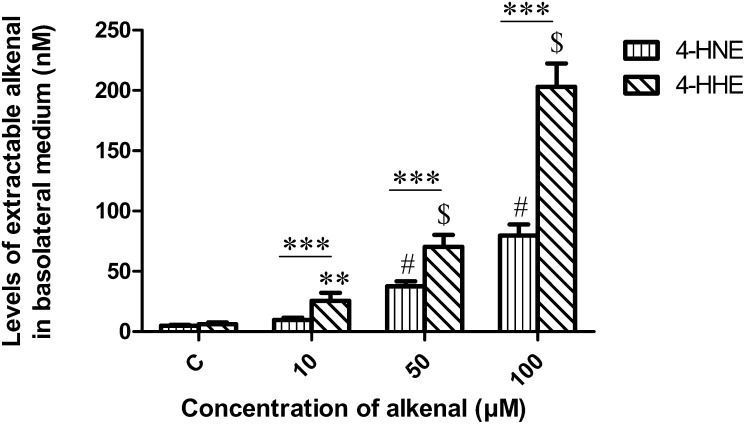

Fig. 5 shows that the basolateral medium (BLM) concentration of 4-HHE was significantly increased in a dose-dependent manner (P < 0.01 versus control). Meanwhile, 4-HNE was increased from 50 µM compared with untreated cells. Detected 4-hydroxy-2-alkenals concentrations in BLM corresponded to ∼0.2–1% of incubated amount. Noticeably, using similar concentrations, 4-HHE was more abundant in the BLM than 4-HNE (P < 0.0001).

Fig. 5.

Concentration of 4-HHE and 4-HNE released in the basolateral medium of Caco-2/TC7 cells after treatment with increasing concentrations of 4-hydroxy-2-alkenal in the apical medium for 24 h. Bars represent means ± SEM of four individual experiments. ***P < 0.0001, $,#P < 0.0001 versus control, **P < 0.01 versus control. ANOVA followed by Fisher test.

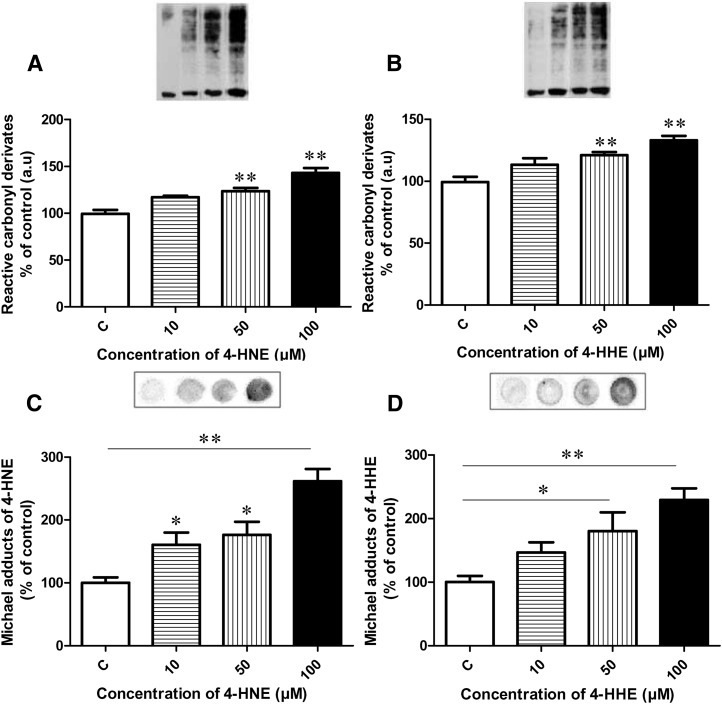

Protein modifications by 4-hydroxy-2-alkenals in Caco-2/TC7 cells

We quantified protein carbonylation and the formation of aldehyde-protein adducts. Cell incubated for 24 h with increasing concentrations of 4-HHE or 4-HNE exhibited an increased level of reactive carbonyl group in proteins in a dose-dependent manner from 50 µM (P < 0.0001) versus untreated cells (Fig. 6A, B). Fig. 6C also reveals a significant increase of HNE-protein adducts after incubating cells for 2 h with 4-HNE from 10 µM in a dose-dependent manner versus untreated cells. Similar treatment using 4-HHE resulted in increased amounts of HHE-protein adducts from 50 µM (P < 0.05; Fig. 6D).

Fig. 6.

Densitometry analysis of protein carbonylation in the Caco-2/TC7 cells after treatment with increasing concentrations of 4-HNE (A) or 4-HHE (B) for 24 h. 4-HNE-protein adducts (C) and 4-HHE-protein adducts (D) in the Caco-2/TC7 cells after treatment with increasing concentrations for 2 h. Bars represent means ± SEM of three individual experiments. **P < 0.01 versus control; *P < 0.05. ANOVA followed by Fisher test.

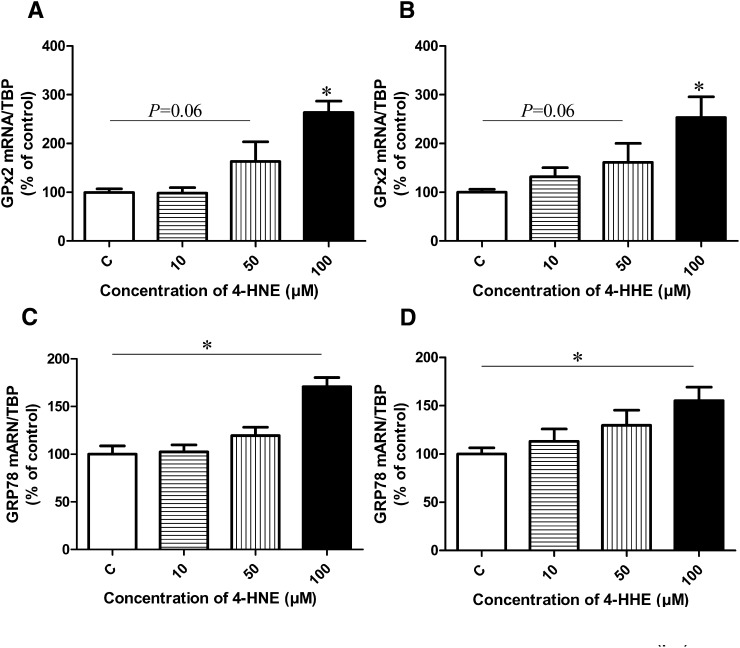

GPx2 and ER stress-linked gene expression in Caco-2/TC7 cells

We then sought to determine whether some antioxidant systems were changed due to 4-hydroxy-2-alkenals. Fig. 7A and B shows that GPx2 expression tended to increase after 24 h at 50 µM of either 4-HNE or 4-HHE (P = 0.06) and significantly increased at a concentration of 100 µM (P < 0.05) compared with control. Moreover, 4-HNE and 4-HHE (100 µM) led to increased expression of GRP78 (P < 0.05) (Fig. 7C, D).

Fig. 7.

Effect of increasing concentrations of 4-HNE or 4-HHE on GPx2 (A, B) and GRP78 (C, D) mRNA expression in Caco-2/TC7 cells after 24 h of treatment. This analysis was quantified by qPCR. Bars represent means ± SEM of three individual experiments. Values are normalized to the levels of TBP mRNA and expressed as relative amount compared with untreated cells. *P < 0.05 versus control. ANOVA followed by Fisher test.

DISCUSSION

This study is the first to highlight the effects of weakly oxidized dietary n-3 PUFA after ingestion on several markers of oxidative stress and inflammation. We tested the hypotheses that a long-term intake of limited amounts of oxidized n-3 PUFA, chosen to mimic oxidized n-3 levels that can be encountered in foodstuffs, enhances markers of oxidative stress and inflammation in mice, partly due to intestinal absorption of 4-HHE.

We show for the first time that the plasma concentration of 4-HHE, a marker of n-3 PUFA lipid peroxidation (23), was increased after chronic intake of oxidized n-3 PUFA. In lipid mixtures, the level of 4-HHE was higher in oxidized oils compared with unoxidized oils. We therefore propose the possibility of a partial intestinal absorption of 4-HHE contained in the diet. Results indeed show that gavage with 4-HHE transiently increased the plasma concentration of 4-HHE in mice. The increase of plasma 4-HHE may be attributed to absorption of exogenously fed 4-HHE; while keeping in mind that a deduction on the bioavailability of 4-HHE cannot be made from the present study due to the lack of deeper pharmacokinetic data. In vitro, Caco-2 cell study confirms that up to 1% of the amount of 4-HHE incubated can be absorbed despite its high reactivity within cells. Moreover, lower amounts of 4-HNE than 4-HHE were found in BLM, suggesting that 4-HNE is less absorbed by the intestine. Of note, 4-HNE is more lipophilic than 4-HHE (23), which could explain its lower absorption and lower abundance in plasma. A 2.8-fold higher level of plasma 4-HHE was observed in the diet study (TG-ox diet, 8 nmol of 4-HHE ingested per day as measured in lipid mixture) compared with acute gavage (single oral 4-HHE intake, 13.2 nmol). 4-HHE may thus partly accumulate in plasma after long-term dietary intake.

Regarding the clinical relevance of plasma 4-HHE concentrations observed in this study, limited data are available about the concentration of 4-HHE in human blood in relation to diet. Indeed, in healthy men supplemented with gradually increasing doses of DHA up to 1,600 mg per day during 8 weeks, a concomitant increase in plasma 4-HHE was observed from 1 ng/ml to 11 ng/ml; i.e., concentrations of ∼100 nM at the end of the 8 week dietary period (24). In our study, the animals were fed during 8 weeks with diets enriched in n-3 PUFA, resulting in similar plasma 4-HHE concentrations; i.e., ∼90 nM in PL group and ∼120 nM in TG group. Therefore, the plasma 4-HHE level after feeding unoxidized n-3 PUFA containing diets is of a similar order to those reported by Calzada et al. (24). Moreover, they demonstrated that high DHA supplementation (between 800 and 1600 mg/day) causes a significant increase in plasma levels of 4-HHE. This was attributed by the authors to the in vivo generation of oxidative stress due to DHA accumulation in the body (24). According to our results, we raise the question of whether this may be due to some degree of DHA oxidation occurring during the preparation and storage of oil capsules or after ingestion. Our results demonstrate for the first time that intestinal absorption of 4-hydroxy-2-alkenals can occur both in vivo and in vitro and that moderate and realistic PUFA oxidation in the diet can significantly increase the plasma 4-HHE concentration.

Regarding the practical relevance of dietary origin of oxidation products in humans, few studies to date have measured the concentrations of 4-hydroxy-2-alkenals in foodstuff. Surh et al. reported that the Korean daily exposure to 4-hydroxy-2-alkenals was 14 nmol/day for 4-HHE and 17 nmol/day for 4-HNE (25). In our study, the quantity of ingested 4-HHE per day as the one measured in lipid mixtures of high-fat diets was in the range 1–8 nmol/day. This is slightly lower than in Surh et al. study (25); nevertheless, our experimental conditions were relevant considering realistic food intakes.

Many of the biological effects of 4-hydroxy-2-alkenals are due to their capacity to react with the nucleophilic sites of proteins to form Michael or Schiff base protein adducts (13, 26) that can be implicated in several diseases, such as diabetes (27), atherosclerosis (28), and neurodegenerative diseases (14, 16). Here we found that when 4-HHE was orally administrated to mice, it reacted with functional proteins to form adducts in the duodenum and, to a lower extent, in the jejunum. Our in vitro study confirms this adduction on absorptive cells. Because the implication of the intestinal barrier in the development of metabolic diseases has been revealed recently (29), the metabolic impact of intestinal alterations by dietary oxidation products deserves further exploration.

To date, the link between the quality of dietary PUFA (n-6 versus n-3) and inflammation has been largely studied, but little is known about the contribution of weak PUFA oxidation in inflammation. We show here that the oxidized n-3 PUFA diet induced higher IL-6, MCP-1 in plasma, and activation of transcription factor NF-κB in intestinal mucosa than did the unoxidized diet. Because the NF-κB pathway is implicated in the regulation of genes involved in inflammation (30), altogether our results suggest a link between oxidized n-3 PUFA and metabolic inflammation. Moreover, among cell lineages in the intestine, Paneth cells are involved in innate immune defense. Their depletion or a reduced expression of the Paneth cell defensins HD5 and HD6 is reported in several pathologies (31–33). Importantly, we show for the first time that dietary oxidized lipids induce a decrease in Paneth cell number in the duodenum. This decrease of Lyz-1 expression, a marker of Paneth cells, is confined to the duodenum. Our results raise the question of whether this effect could have contributed to the increase of the systemic inflammation.

In the gastrointestinal tract, a defense system including gastrointestinal glutathione peroxidase is known to detoxify and degrade lipid peroxidation products (34), and protect against inflammation (35). Feeding animals with highly oxidized n-6 fat was reported to increase the expression of markers of intestine antioxidant defense (36, 37). Here we show a significant increase in GPx2 mRNA after incubation of Caco-2 cells with 4-HHE or 4-HNE in the jejunum of mice fed moderately oxidized diet and in the duodenum of mice directly force-fed with 4-HHE. Interestingly, in the force-fed mice, GPx2 expression was highest in the intestinal segment presenting the greatest amount of protein adducts. Thus, the intake of oxidized PUFA or some of their components, such as 4-hydroxy-2-alkenals, affected the antioxidant defense system. GPx2 appears here to reflect the activation of a metabolic path for detoxifying 4-hydroxy-2-alkenals and adducts, either generated in the gut or introduced via the diet.

GRP78 is widely considered as a common regulator/sensor of ER stress. Overexpression of GRP78 is induced by a variety of environmental stress conditions, leading to impairment of essential ER functions in order to maintain cell viability against oxidative stress and apoptosis (38). In addition, ER stress induces genes encoding non-ER proteins such as CHOP associated with growth arrest and induction to apoptosis (39). ER stress may also result from protein denaturation due to carbonylation and/or covalent adduct formation with 4-hydroxy-2-alkenals. We demonstrate for the first time the implication of oxidized PUFA or their end-products in ER stress in the upper gastrointestinal tract (duodenum and jejunum) through induction of GRP78 and CHOP expressions. It is important to note that the effects of oxidized lipids on the stress markers are different along the intestine, with the most significant effect in the jejunum regardless of oil type. Further investigations are needed to clarify the possible interactions between inflammation and ER stress in the different segments of the intestine in response to oxidized lipids. On the other hand, the expression of GRP78 was reported to increase under conditions of chronic inflammation in the intestine, including active Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis (40). In our study, observed upregulation of GPx2 and GRP78 can be associated with i) protein adducts and further activation of NF-κB and ii) induction of a protective mechanism against oxidative stress and inflammation. The increase of NF-κB activation is consistent with published data. Indeed, Shkoda et al. demonstrated that the increased level of GRP78 induces the activation of NF-κB through the phosphorylation of IKK complex in the intestinal epithelial cells (40). Furthermore, Je et al. showed that the activation of NF-κB by 4-HHE can occur via the NIK/IKK and p38 MAPK pathway in the endothelial cells (41).

In the present study, the PL-ox lipid blend contained lower detectable amounts of 4-HHE than did the TG-ox lipid blend. However, both types of oxidized n-3 PUFA-containing diets resulted in significant metabolic effects of similar magnitude, especially regarding plasma inflammation and stress markers in the jejunum. This suggests that inflammatory responses are not a simple reflection of the content of n-3 PUFA, in either the diet or the plasma, or of the dietary 4-HHE content. We cannot rule out that observed effects can be due to other bioactive species than 4-hydroxy-alkenals. For example, oxidized phospholipids by themselves have been reported to be proinflammatory (42, 43); advanced oxidation protein products could also contribute to observed effects (44, 45).

In conclusion, our study demonstrates in mice that long-term ingestion of weakly oxidized n-3 PUFA induces an accumulation of 4-HHE in plasma, which can be partly due to 4-HHE absorption in the small intestine. Furthermore, weakly oxidized n-3 PUFA enhance inflammatory markers in plasma and ER stress in the upper small intestine and reduce Paneth cell number in the duodenum, possibly through the biological reactivity of 4-HHE. GPx2 appears to be required to defend against injury by oxidative stress markers and prevent inflammation in the intestine. The upregulation of GPx2 and GRP78 can be considered as an attempt to counteract increased inflammation and oxidative stress, noticed by the formation of Michael adducts and reactive carbonyls on intestinal proteins. Altogether, we highlight that the potential harmful effects of dietary oxidized n-3 PUFA, even if consumed in moderate doses, should be taken into account in several pathologies. It appears of utmost importance in medical and nutritional practice to formulate and handle n-3 PUFA-rich foods or supplements with the greatest care to avoid any PUFA oxidation. This can be particularly relevant in patients suffering from acute or chronic diseases who increase their n-3 PUFA intake because of their reported health benefits.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

M. Awada acknowledges her PhD grant from ANR. The authors thank Lucie Ribourg and Michèle Viau for their work on oil mixtures. Patricia Daira is acknowledged for her help with the 4-hydroxy-2-alkenal assay. The authors thank Jean-Michel Chardigny for useful discussions. Isabelle Jouanin (Plateforme AXIOM-MetaToul, Toulouse) is acknowledged for the synthesis of internal standards to measure 4-hydroxyl-2-alkenals in fat. Yvonne Masson is acknowledged for revising the English-language manuscript.

Footnotes

Abbreviations:

- 4-HHE

- 4-hydroxy-2-hexenal

- 4-HNE

- 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal

- BLM

- basolateral medium

- CHOP

- C/EBP homologous protein

- DHA

- docosahexaenoic acid

- EPA

- eicosapentaenoic acid

- ER

- endoplasmic reticulum

- GPx2

- gastrointestinal glutathione peroxidase 2

- GRP78

- glucose-regulated protein 78

- HF

- high fat

- IL

- interleukin

- IP

- intraperitoneal

- Lyz-1

- lysozyme 1

- MCP-1

- monocyte chemotactic protein-1

- NF-κB

- nuclear factor kappaB

- PL

- phospholipid

- TAG

- plasma triacylglcyerol

- TG

- dietary triacylglycerol

- WAT

- white adipose tissue

This work was supported by the French National Research Agency (ANR) Grant ANR-08-ALIA-002, AGECANINOX project.

The online version of this article (available at http://www.jlr.org) contains supplementary data in the form of one table.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hotamisligil G. S. 2006. Inflammation and metabolic disorders. Nature. 444: 860–867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Manabe I. 2011. Chronic inflammation links cardiovascular, metabolic and renal diseases. Circ. J. 75: 2739–2748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zulet M. A., Puchau B., Navarro C., Marti A., Martinez J. A. 2007. Inflammatory biomarkers: the link between obesity and associated pathologies. Nutr. Hosp. 22: 511–527 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fedor D., Kelley D. S. 2009. Prevention of insulin resistance by n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care. 12: 138–146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fetterman J. W., Jr, Zdanowicz M. M. 2009. Therapeutic potential of n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids in disease. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm. 66: 1169–1179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parra D., Bandarra N. M., Kiely M., Thorsdottir I., Martinez J. A. 2007. Impact of fish intake on oxidative stress when included into a moderate energy-restricted program to treat obesity. Eur. J. Nutr. 46: 460–467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carpentier Y. A., Portois L., Malaisse W. J. 2006. n-3 fatty acids and the metabolic syndrome. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 83: 1499S–1504S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Simopoulos A. P. 2008. The importance of the omega-6/omega-3 fatty acid ratio in cardiovascular disease and other chronic diseases. Exp. Biol. Med. (Maywood). 233: 674–688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tanito M., Brush R. S., Elliott M. H., Wicker L. D., Henry K. R., Anderson R. E. 2009. High levels of retinal membrane docosahexaenoic acid increase susceptibility to stress-induced degeneration. J. Lipid Res. 50: 807–819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Esterbauer H., Schaur R. J., Zollner H. 1991. Chemistry and biochemistry of 4-hydroxynonenal, malonaldehyde and related aldehydes. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 11: 81–128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guichardant M., Bacot S., Moliere P., Lagarde M. 2006. Hydroxy-alkenals from the peroxidation of n-3 and n-6 fatty acids and urinary metabolites. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fatty Acids. 75: 179–182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bacot S., Bernoud-Hubac N., Chantegrel B., Deshayes C., Doutheau A., Ponsin G., Lagarde M., Guichardant M. 2007. Evidence for in situ ethanolamine phospholipid adducts with hydroxy-alkenals. J. Lipid Res. 48: 816–825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guichardant M., Taibi-Tronche P., Fay L. B., Lagarde M. 1998. Covalent modifications of aminophospholipids by 4-hydroxynonenal. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 25: 1049–1056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bradley M. A., Xiong-Fister S., Markesbery W. R., Lovell M. A. 2012. Elevated 4-hydroxyhexenal in Alzheimer's disease (AD) progression. Neurobiol. Aging. 33: 1034–1044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mattson M. P. 2009. Roles of the lipid peroxidation product 4-hydroxynonenal in obesity, the metabolic syndrome, and associated vascular and neurodegenerative disorders. Exp. Gerontol. 44: 625–633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shibata N., Yamada S., Uchida K., Hirano A., Sakoda S., Fujimura H., Sasaki S., Iwata M., Toi S., Kawaguchi M., et al. 2004. Accumulation of protein-bound 4-hydroxy-2-hexenal in spinal cords from patients with sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Brain Res. 1019: 170–177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Soulère L., Queneau Y., Doutheau A. 2007. An expeditious synthesis of 4-hydroxy-2E-nonenal (4-HNE), its dimethyl acetal and of related compounds. Chem. Phys. Lipids. 150: 239–243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Michalski M. C., Calzada C., Makino A., Michaud S., Guichardant M. 2008. Oxidation products of polyunsaturated fatty acids in infant formulas compared to human milk–a preliminary study. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 52: 1478–1485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lefils J., Geloen A., Vidal H., Lagarde M., Bernoud-Hubac N. 2010. Dietary DHA: time course of tissue uptake and effects on cytokine secretion in mice. Br. J. Nutr. 104: 1304–1312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mendes R., Cardoso C., Pestana C. 2009. Measurement of malondialdehyde in fish: a comparison study between HPLC methods and the traditional spectrophotometric test. Food Chem. 112: 1038–1045 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Seljeskog E., Hervig T., Mansoor M. A. 2006. A novel HPLC method for the measurement of thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS). A comparison with a commercially available kit. Clin. Biochem. 39: 947–954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nourooz-Zadeh J., Tajaddini-Sarmadi J., Wolff S. P. 1994. Measurement of plasma hydroperoxide concentrations by the ferrous oxidation-xylenol orange assay in conjunction with triphenylphosphine. Anal. Biochem. 220: 403–409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Riahi Y., Cohen G., Shamni O., Sasson S. 2010. Signaling and cytotoxic functions of 4-hydroxyalkenals. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 299: E879–E886 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Calzada C., Colas R., Guillot N., Guichardant M., Laville M., Vericel E., Lagarde M. 2010. Subgram daily supplementation with docosahexaenoic acid protects low-density lipoproteins from oxidation in healthy men. Atherosclerosis. 208: 467–472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Surh J., Lee S., Kwon H. 2007. 4-hydroxy-2-alkenals in polyunsaturated fatty acids-fortified infant formulas and other commercial food products. Food Addit. Contam. 24: 1209–1218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Uchida K. 2003. Histidine and lysine as targets of oxidative modification. Amino Acids. 25: 249–257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pillon N. J., Vella R. E., Souleere L., Becchi M., Lagarde M., Soulage C. O. 2011. Structural and functional changes in human insulin induced by the lipid peroxidation byproducts 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal and 4-hydroxy-2-hexenal. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 24: 752–762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Uchida K., Toyokuni S., Nishikawa K., Kawakishi S., Oda H., Hiai H., Stadtman E. R. 1994. Michael addition-type 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal adducts in modified low-density lipoproteins: markers for atherosclerosis. Biochemistry. 33: 12487–12494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Catalioto R. M., Maggi C. A., Giuliani S. 2011. Intestinal epithelial barrier dysfunction in disease and possible therapeutical interventions. Curr. Med. Chem. 18: 398–426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lawrence T., Gilroy D. W., Colville-Nash P. R., Willoughby D. A. 2001. Possible new role for NF-kappaB in the resolution of inflammation. Nat. Med. 7: 1291–1297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hodin C. M., Verdam F. J., Grootjans J., Rensen S. S., Verheyen F. K., Dejong C. H., Buurman W. A., Greve J. W., Lenaerts K. 2011. Reduced Paneth cell antimicrobial protein levels correlate with activation of the unfolded protein response in the gut of obese individuals. J. Pathol. 225: 276–284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Koslowski M. J., Beisner J., Stange E. F., Wehkamp J. 2010. Innate antimicrobial host defense in small intestinal Crohn's disease. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 300: 34–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schaart M. W., de Bruijn A. C., Bouwman D. M., de Krijger R. R., van Goudoever J. B., Tibboel D., Renes I. B. 2009. Epithelial functions of the residual bowel after surgery for necrotising enterocolitis in human infants. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 49: 31–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wingler K., Muller C., Schmehl K., Florian S., Brigelius-Flohe R. 2000. Gastrointestinal glutathione peroxidase prevents transport of lipid hydroperoxides in CaCo-2 cells. Gastroenterology. 119: 420–430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Esworthy R. S., Yang L., Frankel P. H., Chu F. F. 2005. Epithelium-specific glutathione peroxidase, Gpx2, is involved in the prevention of intestinal inflammation in selenium-deficient mice. J. Nutr. 135: 740–745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Olivero David R., Bastida S., Schultz A., Gonzalez Torres L., Gonzalez-Munoz M. J., Sanchez-Muniz F. J., Benedi J. 2010. Fasting status and thermally oxidized sunflower oil ingestion affect the intestinal antioxidant enzyme activity and gene expression of male Wistar rats. J. Agric. Food Chem. 58: 2498–2504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Varady J., Eder K., Ringseis R. 2011. Dietary oxidized fat activates the oxidative stress-responsive transcription factors NF-kappaB and Nrf2 in intestinal mucosa of mice. Eur. J. Nutr. 50: 601–609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ni M., Zhang Y., Lee A. S. 2011. Beyond the endoplasmic reticulum: atypical GRP78 in cell viability, signalling and therapeutic targeting. Biochem. J. 434: 181–188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Oyadomari S., Mori M. 2004. Roles of CHOP/GADD153 in endoplasmic reticulum stress. Cell Death Differ. 11: 381–389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shkoda A., Ruiz P. A., Daniel H., Kim S. C., Rogler G., Sartor R. B., Haller D. 2007. Interleukin-10 blocked endoplasmic reticulum stress in intestinal epithelial cells: impact on chronic inflammation. Gastroenterology. 132: 190–207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Je J. H., Lee J. Y., Jung K. J., Sung B., Go E. K., Yu B. P., Chung H. Y. 2004. NF-kappaB activation mechanism of 4-hydroxyhexenal via NIK/IKK and p38 MAPK pathway. FEBS Lett. 566: 183–189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Greig F. H., Kennedy S., Spickett C. M. 2012. Physiological effects of oxidized phospholipids and their cellular signaling mechanisms in inflammation. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 52: 266–280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tseng W., Lu J., Bishop G. A., Watson A. D., Sage A. P., Demer L., Tintut Y. 2010. Regulation of interleukin-6 expression in osteoblasts by oxidized phospholipids. J. Lipid Res. 51: 1010–1016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Unoki H., Bujo H., Yamagishi S., Takeuchi M., Imaizumi T., Saito Y. 2007. Advanced glycation end products attenuate cellular insulin sensitivity by increasing the generation of intracellular reactive oxygen species in adipocytes. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 76: 236–244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhou Q. G., Zhou M., Lou A. J., Xie D., Hou F. F. 2010. Advanced oxidation protein products induce inflammatory response and insulin resistance in cultured adipocytes via induction of endoplasmic reticulum stress. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 26: 775–786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chiang Y. F., Shaw H. M., Yang M. F., Huang C. Y., Hsieh C. H., Chao P. M. 2011. Dietary oxidised frying oil causes oxidative damage of pancreatic islets and impairment of insulin secretion, effects associated with vitamin E deficiency. Br. J. Nutr. 105: 1311–1319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.