Abstract

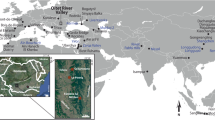

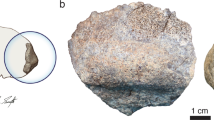

Who the first inhabitants of Western Europe were, what their physical characteristics were, and when and where they lived are some of the pending questions in the study of the settlement of Eurasia during the Early Pleistocene epoch. The available palaeoanthropological information from Western Europe is limited and confined to the Iberian Peninsula1,2. Here we present most of the midface of a hominin found at the TE7 level of the Sima del Elefante site (Sierra de Atapuerca, Spain), dated to between 1.4 million and 1.1 million years ago. This fossil (ATE7-1) represents the earliest human face of Western Europe identified thus far. Most of the morphological features of the midface of this hominin are primitive for the Homo clade and they do not display the modern-like aspect exhibited by Homo antecessor found at the neighbouring Gran Dolina site, also in the Sierra de Atapuerca, and dated to between 900,000 and 800,000 years ago3. Furthermore, ATE7-1 is more derived in the nasoalveolar region than the Dmanisi and other roughly contemporaneous hominins. On the basis of the available evidence, it is reasonable to assign the new human remains from TE7 level to Homo aff. erectus. From the archaeological, palaeontological and palaeoanthropological information obtained in the lower levels of the Sima del Elefante and Gran Dolina sites4,5,6,7,8, we suggest a turnover in the human population in Europe at the end of the Early Pleistocene.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

$199.00 per year

only $3.90 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

Correspondence and requests data/materials should be addressed to R.H., X.P.R.-Á., J.M.B.d.C. and M.M.-T.

Change history

01 April 2025

In the version of Supplementary Information originally published alongside this article, the legends for Supplementary Figs. 4.2, 4.5, 4.6, and 4.9 were truncated, and are now amended in the revised Supplementary Information available online.

References

Carbonell, E. et al. The first hominin of Europe. Nature 452, 465–469 (2008).

Toro-Moyano, I. et al. The oldest human fossil in Europe, from Orce (Spain). J. Hum. Evol. 65, 1–9 (2013).

Duval, M. et al. The first direct ESR dating of a hominin tooth from Atapuerca Gran Dolina TD-6 (Spain) supports the antiquity of Homo antecessor. Quat. Geochronol. 47, 120–137 (2018).

Bermúdez de Castro, J. M. et al. A hominid from the Lower Pleistocene of Atapuerca, Spain: possible ancestor to Neandertals and modern humans. Science 276, 1392–1395 (1997).

Cuenca-Bescós, G. et al. Comparing two different Early Pleistocene microfaunal sequences from the caves of Atapuerca, Sima del Elefante and Gran Dolina (Spain): biochronological implications and significance of the Jaramillo subchron. Quat. Int. 389, 148–158 (2015).

Huguet, R. et al. Successful subsistence strategies of the first humans in south-western Europe. Quat. Int. 295, 168–182 (2013).

Parés, J. M. et al. Chronology of the cave interior sediments at Gran Dolina archaeological site, Atapuerca (Spain). Quat. Sci. Rev. 186, 1–16 (2018).

Carbonell, E., Rodríguez-Álvarez, X. P., Parés, J. M., Huguet, R. & Rosell, J. The earliest human occupation of Atapuerca in the European context. Anthropologie 128, 103233 (2024).

Gabunia, L. et al. Earliest pleistocene hominid cranial remains from Dmanisi, Republic of Georgia: taxonomy, geological setting, and age. Science 288, 1019–1025 (2000).

Garcia, T. et al. Earliest human remains in Eurasia: new 40Ar/39Ar dating of the Dmanisi hominid-bearing levels, Georgia. Quat. Geochronol. 5, 443–451 (2010).

Oms, O. et al. Early human occupation of Western Europe: paleomagnetic dates for two paleolithic sites in Spain. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 97, 10666–10670 (2000).

Lorenzo, C. et al. Early Pleistocene human hand phalanx from the Sima del Elefante (TE) cave site in Sierra de Atapuerca (Spain). J. Hum. Evol. 78, 114–121 (2015).

Bermúdez De Castro, J. M. et al. Early Pleistocene human mandible from Sima del Elefante (TE) cave site in Sierra de Atapuerca (Spain): a comparative morphological study. J. Hum. Evol. 61, 12–25 (2011).

Fernández-Jalvo, Y., Díez, J. C., Bermúdez de Castro, J. M., Carbonell, E. & Arsuaga, J. L. Evidence of early cannibalism. Science 271, 277–278 (1996).

Díez, J. C., Fernández-Jalvo, Y., Rosell, J. & Cáceres, I. Zooarchaeology and taphonomy of Aurora Stratum (Gran Dolina, Sierra de Atapuerca, Spain). J. Hum. Evol. 37, 623–652 (1999).

Saladié, P. et al. Dragged, lagged, or undisturbed: reassessing the autochthony of the hominin-bearing assemblages at Gran Dolina (Atapuerca, Spain). Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 13, 65 (2021).

Parés, J. M. & Pérez-González, A. Paleomagnetic age for hominid fossils at Atapuerca archaeological site, Spain. Science 269, 830–832 (1995).

Falguères, C. et al. Earliest humans in Europe: the age of TD6 Gran Dolina, Atapuerca, Spain. J. Hum. Evol. 37, 343–352 (1999).

Freidline, S. E., Gunz, P., Harvati, K. & Hublin, J.-J. Evaluating developmental shape changes in Homo antecessor subadult facial morphology. J. Hum. Evol. 65, 404–423 (2013).

Lacruz, R. S. et al. Facial morphogenesis of the earliest Europeans. PLoS ONE 8, e65199 (2013).

Lacruz, R. S. et al. The evolutionary history of the human face. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 3, 726–736 (2019).

Rosas, A. et al. Le gisement pléistocène de la «Sima del Elefante å (Sierra de Atapuerca, Espagne). Anthropologie 105, 301–312 (2001).

Rosas, A. et al. The “Sima del Elefante” cave site at Atapuerca (Spain). Estud. Geol. 62, 327–348 (2006).

Huguet, R. et al. Level TE9c of Sima del Elefante (Sierra de Atapuerca, Spain): a comprehensive approach. Quat. Int. 433, 278–295 (2017).

De Lombera-Hermida, A. et al. The lithic industry of Sima del Elefante (Atapuerca, Burgos, Spain) in the context of Early and Middle Pleistocene technology in Europe. J. Hum. Evol. 82, 95–106 (2015).

Cuenca-Bescós, G. et al. The small mammals of Sima del Elefante (Atapuerca, Spain) and the first entrance of Homo in Western Europe. Quat. Int. 295, 28–35 (2013).

Cuenca-Bescós, G. et al. Updated Atapuerca biostratigraphy: small-mammal distribution and its implications for the biochronology of the Quaternary in Spain. C. R. Palevol 15, 621–634 (2016).

Maureille, B. La Face Chez Homo erectus et Homo sapiens: Recherche Sur La Variabilite Morphologique et Métrique. PhD thesis, Univ. Bourdeux I (1994).

Weidenreich, F. The skull of Sinanthropus pekinensis: a comparative study. Paleontol. Sin. N. D 10, 1–484 (1943).

Rightmire, G. P., Lordkipanidze, D. & Vekua, A. Anatomical descriptions, comparative studies and evolutionary significance of the hominin skulls from Dmanisi, Republic of Georgia. J. Hum. Evol. 50, 115–141 (2006).

Rightmire, G. P., Ponce De León, M. S., Lordkipanidze, D., Margvelashvili, A. & Zollikofer, C. P. E. Skull 5 from Dmanisi: descriptive anatomy, comparative studies, and evolutionary significance. J. Hum. Evol. 104, 50–79 (2017).

Ungar, P. S., Grine, F. E., Teaford, M. F. & Pérez-Pérez, A. A review of interproximal wear grooves on fossil hominin teeth with new evidence from Olduvai Gorge. Arch. Oral Biol. 46, 285–292 (2001).

Xing, S., Martinón-Torres, M. & Bermúdez de Castro, J. M. The fossil teeth of the Peking Man. Sci. Rep. 8, 2066 (2018).

Franciscus, R. G. Internal nasal floor configuration in Homo with special reference to the evolution of Neandertal facial form. J. Hum. Evol. 44, 701–729 (2003).

Schwartz, J. H., Pantoja-Pérez, A. & Arsuaga, J. L. The nasal region of the 417 ka Sima de los Huesos (Sierra de Atapuerca, Spain) Hominin: new terminology and implications for later human evolution. Anat. Rec. 305, 1991–2029 (2022).

McCollum, M. A. Subnasal morphological variation in fossil hominids: a reassessment based on new observations and recent developmental findings. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 112, 275–283 (2000).

Terradillos-Bernal, M., Zorrilla-Revilla, G. & Rodríguez-Álvarez, X.-P. To be or not to be a lithic tool: analysing the limestone pieces of Sima del Elefante (Sierra de Atapuerca, northern Spain). Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 14, 189 (2022).

Nuñez-Lahuerta, C., Cuenca-Bescós, G. & Huguet, R. First report on the birds (Aves) from level TE7 of Sima del Elefante (Early Pleistocene) of Atapuerca (Spain). Quat. Int. 421, 12–22 (2016).

Galán, J., Cuenca-Bescós, G. & López-García, J. M. The fossil bat assemblage of Sima del Elefante Lower Red Unit (Atapuerca, Spain): first results and contribution to the palaeoenvironmental approach to the site. C. R. Palevol 15, 647–657 (2016).

Rightmire, G. P. Evidence from facial morphology for similarity of Asian and African representatives of Homo erectus. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 106, 61–85 (1998).

Barsky, D. et al. The significance of subtlety: contrasting lithic raw materials procurement and use patterns at the Oldowan sites of Barranco León and Fuente Nueva 3 (Orce, Andalusia, Spain). Front. Earth Sci. 10, 893776 (2022).

Cauche, D. The Vallonnet cave on the northern Mediterranean border: a record of one of the oldest human presences in Europe. Anthropologie 126, 102974 (2022).

Despriée, J. et al. The 1-million-year-old quartz assemblage from Pont-de-Lavaud (Centre, France) in the European context. J. Quat. Sci. 33, 639–661 (2018).

Vialet, A., Prat, S., Wils, P. & Cihat Alçiçek, M. The Kocabaş hominin (Denizli Basin, Turkey) at the crossroads of Eurasia: new insights from morphometric and cladistic analyses. C. R. Palevol 17, 17–32 (2018).

Arzarello, M., De Weyer, L. & Peretto, C. The first European peopling and the Italian case: peculiarities and “opportunism”. Quat. Int. 393, 41–50 (2016).

Duval, M. et al. Re-examining the earliest evidence of human presence in western Europe: new dating results from Pirro Nord (Italy). Quat. Geochronol. 82, 101519 (2024).

Garba, R. et al. East-to-west human dispersal into Europe 1.4 million years ago. Nature 627, 805–810 (2024).

Margari, V. et al. Extreme glacial cooling likely led to hominin depopulation of Europe in the Early Pleistocene. Science 381, 693–699 (2023).

Rodríguez, J. et al. One million years of cultural evolution in a stable environment at Atapuerca (Burgos, Spain). Quat. Sci. Rev. 30, 1396–1412 (2011).

Hu, W. et al. Genomic inference of a severe human bottleneck during the Early to Middle Pleistocene transition. Science 381, 979–984 (2023).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge all of the members of the Atapuerca research team involved in the recovery and study of the archaeological and palaeontological record from Sima del Elefante site. The research of the Atapuerca sites is founding by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation and European Regional Development Fund “ERDF A way of making Europe” (projects PID2021-122355NB-C31, PID2021-122355NB-C32, PID2021-22355NB-C33). Fieldwork at Sima del Elefante is supported by the Junta de Castilla y León and the Fundación Atapuerca. The Institut Català de Paleoecologia Humana i Evolució Social (IPHES-CERCA) has received financial support from the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation through the María de Maeztu program for Units of Excellence (CEX2019-000945-M). We acknowledge support from the Catalan Government (AGAUR, projects 2021-SGR-01237, 2021-SGR-01238 and 2021-SGR-01239) and Universitat Rovira i Virgili (2023PFR-URV-01237, 2023PFR-URV-01238 and 2023PFR-URV-01239). M.M.-T. receives funding from The Leakey Foundation through the personal support of D. Crook. Part of the hominin analyses were carried out at the laboratories of the CENIEH-ICTS with the support of the CENIEH staff. The research of J.M.L.-G. and H.-A.B. was funded by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation and European Regional Development Fund (project PID2021-122533NB-I00). E.S. received funding from Fundación Atapuerca. C.N.-L. was supported by a Juan de la Cierva formation contract (FJC2020-044561-l; MCIN cofinanced by the NextGeneration EU/PRTR). L.M.-F. is supported by Horizon Program-Marie Sklodowska-Curie Actions of the EU Ninth programme (2021–2027) under the HORIZON-MSCA-2021-PF-01-Project: 101060482 and MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and “ERDF A way of making Europe”. J.G. is the beneficiary of a Postdoctoral Fellowship from the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation (ESP-1235332-HFST-P). J.v.d.M. benefited from grant Synthesys AT-TAF-3663. The research of A.R.-H. is supported by the grant RYC2022-037802-I funded by MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and by the FSE invests in your future. A.B. was supported by a Juan de la Cierva—Incorporación contract IJC2019-041546-I and by the grant RYC2022-037783-I. A.P. is supported by the LATEUROPE project (ERC Consolidator Grant ID101052653). A.M. acknowledges the Shota Rustaveli Georgian National Science Foundation (grant YS-21-1595). All of the photographs of the archaeological and palaeontological remains of Sima del Elefante were taken by M. D. Guillén (IPHES-CERCA). The stratigraphic sections of Sima del Elefante were drawn by R. Pérez-Martínez. We thank G. Zorrilla-Revilla and P. Mateo-Lomba for assistance on the microscopy analysis of archaeological remains.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.H., X.P.R.-Á., M.M.-T. and J.M.B.d.C. performed the conceptualization. R.H and X.P.R.-Á. edited and coordinated the manuscript and the fieldwork of Sima del Elefante. J.V. contributed to geology, sedimentology and micromorphology. J.M.B.d.C., M.M.-T., M.L., E.S. and L.M.-F. contributed to palaeoanthropology. E.S. and L.M.-F. contributed to virtual reconstruction. E.M.-R. contributed to preservation and conservation. X.P.R.-Á., M.T.-B., A.O., A.d.L.-H., A.B., M.M and E.C. contributed to stone tool technology. R.H., P.S., I.C., A.R.-H., J.M. and A.P. contributed to zooarchaeology and taphonomy. J.M.L.-G., C.N.-L., J.G., H.-A.B. and J.v.d.M. contributed to palaeontology. I.E. and E.A. contributed to archaeobotany. J.M.P. contributed to geochronology. D.L. and A.M. provided comparative samples. E.C., J.M.B.d.C. and J.L.A. directed the excavations.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature thanks G. Philip Rightmire, Amélie Vialet and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data figures and tables

Extended Data Fig. 1 Comparison of the zygomaxillary border and the zygomaxillary tubercle.

Frontal view of the virtual reconstruction of a) ATE7-1, b) D2282, c) D2700, d) ATD6−69, e) D4500, f) Sangiran 17 and g) ATD6−58. White arrow points to the zygomaxillary border which is curved in H. antecessor (d,g) and straight in the rest of the specimens, including ATE7-1. Red arrow points to the presence of a zygomaxillary tubercle in ATD6−69 and ATD6-58, a feature that seems to be absent in ATE7−1 and in the Early Pleistocene specimens from Dmanisi and Sangiran portrayed for comparison.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Comparison of the slope of the infraorbital plate and the lateral nasal margin.

Lateral view of the virtual reconstruction of a) ATE7−1, b) D2282, c) KNM-ER-3733, d) ATD6-69, e) D4500 and f) Sangiran 17. The lateral nasal margin of H. antecessor is curved, whereas this profile is straight in the rest of the specimens (dashed line 1). The infraorbital plate slopes in an anterior-inferior direction except in ATD6-69, where this surface slopes slightly backwards (dashed line 2).

Extended Data Fig. 3 Comparison of the maxillary flexion.

Virtual reconstruction of ATE7−1 and ATD6-69. a) ATE7−1 superior (left) and inferior (right) view, b) ATD6-69 superior (left) and inferior (right). The arrows and the dash lines indicate the differences in the maxillary flexion between both fossils. Whereas the flexion is present in ATD6-69, this feature is absent in ATE7-1.

Extended Data Fig. 4 General comparison of ATE7-1 with Early Pleistocene specimens from Africa and Eurasia in lateral view.

Lateral view of the superimposition of the virtual reconstruction of ATE7-1 with a) D2282, b) KNM-ER-3733, c) ATD6-69, d) D4500 and e) Sangiran 17. The comparative fossils are in ghost texture while ATE7 is shown in opaque texture. In this figure it is possible to observe that ATE7-1 shares the same rectilinear morphology of the nasal lateral margin as the comparative specimens except for ATD6-69, which has a curved profile. The morphological differences are also obvious with D4500 because of the long and strongly sloped clivus in the Dmanisi specimen versus the shorter and relatively less inclined clivus in ATE7-1.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Comparison of the nasal lateral margin in ATE7-1 and ATD6-69.

Lateral view of the superimposition of the virtual reconstruction of ATE7-1 (opaque texture) and ATD6-69 (ghost texture). The superimposition highlights the straight course of the nasal lateral margin in ATE7-1 versus the more curved trajectory in ATD6-69.

Extended Data Fig. 6 General comparison of ATE7-1 with Early Pleistocene specimens from Africa and Eurasia in frontal view.

Frontal view of the superimposition of the virtual reconstruction of ATE7-1 with a) D2282, b) KNM-ER-3733, c) ATD6-58, d) ATD6-69, e) D4500 and f) Sangiran 17 (mirror reconstruction). The comparative fossils are in ghost texture while ATE7-1 is shown in opaque texture. The comparison highlights the larger facial width of the Early Pleistocene fossils from Africa and Asia due to the anterior projection of their zygomatic bone in comparison to the narrower midface of ATE7-1. Note that the comparison with d) may be influenced by the immature state of this individual.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Sections 1–7, including Supplementary Figs, Tables and References.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Huguet, R., Rodríguez-Álvarez, X.P., Martinón-Torres, M. et al. The earliest human face of Western Europe. Nature 640, 707–713 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-08681-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-08681-0