Abstract

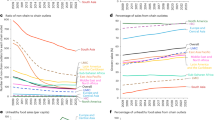

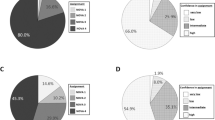

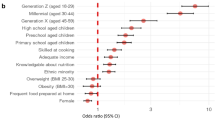

The offering of grocery stores is a strong driver of consumer decisions. While highly processed foods such as packaged products, processed meat and sweetened soft drinks have been increasingly associated with unhealthy diets, information on the degree of processing characterizing an item in a store is not straightforward to obtain, limiting the ability of individuals to make informed choices. GroceryDB, a database with over 50,000 food items sold by Walmart, Target and Whole Foods, shows the degree of processing of food items and potential alternatives in the surrounding food environment. The extensive data gathered on ingredient lists and nutrition facts enables a large-scale analysis of ingredient patterns and degrees of processing, categorized by store, food category and price range. Furthermore, it allows the quantification of the individual contribution of over 1,000 ingredients to ultra-processing. GroceryDB makes this information accessible, guiding consumers toward less processed food choices.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$29.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$119.00 per year

only $9.92 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The data in GroceryDB was scraped from Walmart, Target and Whole Foods in 2021. GroceryDB is available to the public and consumers at https://www.TrueFood.tech/. The data are also openly available on MongoDB servers with a read-only key available via BarabasiLab GitHub repository at https://github.com/Barabasi-Lab/GroceryDB/. The USDA FNDDS dataset is available via the same GitHub repository. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

All code generated for the analysis are available via the BarabasiLab GitHub repository at https://github.com/Barabasi-Lab/GroceryDB/. The analysis was done in Python==3.11.7 with the following packages: jupyter notebook==6.5.4, pymongo==4.8.0, pandas==2.1.4, numpy==1.26.4, seaborn==0.12.2, statsmodels==0.14.0, scipy==1.11.4, matlabplot==3.8.0, plotly==5.9.0 and certifi==2024.6.2.

References

Seferidi, P. et al. The neglected environmental impacts of ultra-processed foods. Lancet Planet. Health 4, e437–e438 (2020).

Fardet, A. & Rock, E. Ultra-processed foods and food system sustainability: what are the links? Sustainability 12, 6280 (2020).

Macdiarmid, J. I. The food system and climate change: are plant-based diets becoming unhealthy and less environmentally sustainable? Proc. Nutr. Soc. 81, 162–167 (2022).

Ambikapathi, R. et al. Global food systems transitions have enabled affordable diets but had less favourable outcomes for nutrition, environmental health, inclusion and equity. Nat. Food 3, 764–779 (2022).

Lane, M. M. et al. Ultra-processed food exposure and adverse health outcomes: umbrella review of epidemiological meta-analyses. BMJ 384, e077310 (2024).

Lustig, R. H. Processed food—an experiment that failed. JAMA Pediatr. 171, 212–214 (2017).

Milanlouei, S. et al. A systematic comprehensive longitudinal evaluation of dietary factors associated with acute myocardial infarction and fatal coronary heart disease. Nat. Commun. 11, 1–14 (2020).

Martínez Steele, E., Popkin, B. M., Swinburn, B. & Monteiro, C. A. The share of ultra-processed foods and the overall nutritional quality of diets in the US: evidence from a nationally representative cross-sectional study. Popul. Health Metr. 15, 6 (2017).

Monteiro, C. A. et al. NOVA. The star shines bright. World Nutr. J. 7, 28–38 (2016).

Steele, E. M. et al. Ultra-processed foods and added sugars in the U.S. diet: evidence from a nationally representative cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 6, e009892 (2016).

Steele, E. M. & Monteiro, C. A. Association between dietary share of ultra-processed foods and urinary concentrations of phytoestrogens in the US. Nutrients 9, 209 (2017).

Adjibade, M. et al. Prospective association between ultra-processed food consumption and incident depressive symptoms in the French NutriNet-Santé cohort. BMC Med. 17, 1–13 (2019).

Fiolet, T. et al. Consumption of ultra-processed foods and cancer risk: results from NutriNet-Santé prospective cohort. BMJ 360, k322 (2018).

Srour, B. et al. Ultra-processed food intake and risk of cardiovascular disease: prospective cohort study (NutriNet-Santé). BMJ 365, l1451 (2019).

Hall, K. D. et al. Ultra-processed diets cause excess calorie intake and weight gain: an inpatient randomized controlled trial of ad libitum food intake. Cell Metab. 30, 1–11 (2019).

Martínez Steele, E., Khandpur, N., da Costa Louzada, M. L. & Monteiro, C. A. Association between dietary contribution of ultra-processed foods and urinary concentrations of phthalates and bisphenol in a nationally representative sample of the US population aged 6 years and older. PLoS ONE 15, 1–21 (2020).

Nerín, C., Aznar, M. & Carrizo, D. Food contamination during food process. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 48, 63–68 (2016).

Rather, I. A., Koh, W. Y., Paek, W. K. & Lim, J. The sources of chemical contaminants in food and their health implications. Front. Pharmacol. 8, 830 (2017).

Arisseto, A. P. Furan in processed foods. In Food Hygiene and Toxicology in Ready-to-Eat Foods (ed. Kotzekidou, P.) Ch. 21, 383–396 (Academic, 2016).

Buckley, J. P., Kim, H., Wong, E. & Rebholz, C. M. Ultra-processed food consumption and exposure to phthalates and bisphenols in the US National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2013–2014. Environ. Int. 131, 105057 (2019).

Mozaffarian, D., Fleischhacker, S. & Andrés, J. R. Prioritizing nutrition security in the US. JAMA 325, 1605–1606 (2021).

Livings, M. S. et al. Food and nutrition insecurity: experiences that differ for some and independently predict diet-related disease, Los Angeles County, 2022. J. Nutr. 154, 2566–2574 (2024).

Food and Nutrition Security (USDA, 2024); https://www.usda.gov/about-usda/general-information/priorities/food-and-nutrition-security

Volpp, K. G. et al. Food is medicine: a presidential advisory from the American Heart Association. Circulation 148, 1417–1439 (2023).

Mozaffarian, D., Andrés, J. R., Cousin, E., Frist, W. H. & Glickman, D. R. The White House Conference on Hunger, Nutrition and Health is an opportunity for transformational change. Nat. Food 3, 561–563 (2022).

Mozaffarian, D., Rosenberg, I. & Uauy, R. History of modern nutrition science-implications for current research, dietary guidelines, and food policy. BMJ 361, k2392 (2018).

Sadler, C. R. et al. Processed food classification: conceptualisation and challenges. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 112, 149–162 (2021).

Gibney, M. J. & Forde, C. G. Nutrition research challenges for processed food and health. Nat. Food 3, 104–109 (2022).

Lacy-Nichols, J. & Freudenberg, N. Opportunities and limitations of the ultra-processed food framing. Nat. Food 3, 975–977 (2022).

Braesco, V. et al. Ultra-processed foods: how functional is the NOVA system? Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 76, 1245–1253 (2022).

Data Crunch Report: The Impact of Bad Data on Profits and Customer Service in the UK Grocery Industry (accessed April 4, 2022) (GS1 UK and Cranfield University School of Management, 2009); https://dspace.lib.cranfield.ac.uk/bitstream/handle/1826/4135/Data_crunch_report.pdf

THE 17 GOALS ∣ Sustainable Development (United Nations, 2020); https://sdgs.un.org/goals

Methods and Standards (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2021); https://www.fao.org/statistics/methods-and-standards/en/

Sarku, R., Clemen, U. A. & Clemen, T. The application of artificial intelligence models for food security: a review. Agriculture 13, 2037 (2023).

Hu, G., Ahmed, M. & L’Abbé, M. R. Natural language processing and machine learning approaches for food categorization and nutrition quality prediction compared with traditional methods. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 117, 553–563 (2023).

Impact Initiative (AI for Good, 2019); https://aiforgood.itu.int/

Menichetti, G., Ravandi, B., Mozaffarian, D. & Barabási, A.-L. Machine learning prediction of the degree of food processing. Nat. Commun. 14, 2312 (2023).

Chen, X. et al. Consumption of ultra-processed foods and health outcomes: a systematic review of epidemiological studies. Nutr. J. 19, 86 (2020).

Mendoza, K. et al. Ultra-processed foods and cardiovascular disease: analysis of three large US prospective cohorts and a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Lancet Reg. Health Am. 37, 100859 (2024).

Slimani, N. et al. Contribution of highly industrially processed foods to the nutrient intakes and patterns of middle-aged populations in the European prospective investigation into cancer and nutrition study. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 63, S206–S225 (2009).

Poti, J. M., Mendez, M. A., Ng, S. W. & Popkin, B. M. Is the degree of food processing and convenience linked with the nutritional quality of foods purchased by US households? Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 101, 1251–1262 (2015).

Davidou, S., Christodoulou, A., Fardet, A. & Frank, K. The holistico-reductionist SIGA classification according to the degree of food processing: an evaluation of ultra-processed foods in French supermarkets. Food Funct. 11, 2026–2039 (2020).

U.S. Population: Consumption of Breakfast Cereals (Cold) from 2011 to 2024 (accessed February 2022) (Statista, 2021); https://www.statista.com/statistics/281995/us-households-consumption-of-breakfast-cereals-cold-trend/

Bray, G. A., Nielsen, S. J. & Popkin, B. M. Consumption of high-fructose corn syrup in beverages may play a role in the epidemic of obesity. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 79, 537–543 (2004).

Guidance for Industry: Food Labeling Guide (accessed 1 November 2021) (USFDA, 2021); https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/guidance-industry-food-labeling-guide

Igoe, R. S. Dictionary of Food Ingredients (Springer Science & Business Media, 2011).

Goyal, A., Sharma, V., Upadhyay, N., Gill, S. & Sihag, M. Flax and flaxseed oil: an ancient medicine & modern functional food. J. Food Sci. Technol. 51, 1633–1653 (2014).

Hashempour-Baltork, F., Torbati, M., Azadmard-Damirchi, S. & Savage, G. P. Vegetable oil blending: a review of physicochemical, nutritional and health effects. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 57, 52–58 (2016).

Whole Foods Mission and Values (accessed 1 March 2022) (2012); https://www.WholeFoodsmarket.com/mission-values

Walmart History (accessed 1 March 2022) (2022); https://corporate.walmart.com/about/history

Gupta, S., Hawk, T., Aggarwal, A. & Drewnowski, A. Characterizing ultra-processed foods by energy density, nutrient density, and cost. Front. Nutr. 6, 70 (2019).

Zenk, S. N., Tabak, L. A. & Pérez-Stable, E. J. Research opportunities to address nutrition insecurity and disparities. JAMA 327, 1953–1954 (2022).

Venkataramani, A. S., O’Brien, R., Whitehorn, G. L. & Tsai, A. C. Economic influences on population health in the United States: toward policymaking driven by data and evidence. PLoS Med. 17, e1003319 (2020).

Erndt-Marino, J., O’Hearn, M. & Menichetti, G. An integrative analytical framework to identify healthy, impactful, and equitable foods: a case study on 100% orange juice. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 74, 668–684 (2023).

Coletro, H. N. et al. The combined consumption of fresh/minimally processed food and ultra-processed food on food insecurity: COVID Inconfidentes, a population-based survey. Public Health Nutr. 26, 1414–1423 (2023).

Hutchinson, J. & Tarasuk, V. The relationship between diet quality and the severity of household food insecurity in Canada. Public Health Nutr. 25, 1013–1026 (2022).

Griffith, R., Jenneson, V., James, J. & Taylor, A. The Impact of a Tax on Added Sugar and Salt. Tech. Rep., IFS Working Paper (IFS, 2021); http://hdl.handle.net/10419/242920

Mozaffarian, D., Blanck, H. M., Garfield, K. M., Wassung, A. & Petersen, R. A Food is Medicine approach to achieve nutrition security and improve health. Nat. Med. 28, 2238–2240 (2022).

The National Food Strategy: The Plan (accessed 23 March 2022) (2019); https://www.nationalfoodstrategy.org/

True Cost of Food: Measuring What Matters to Transform the U.S. Food System (The Rockefeller Foundation, 2021); https://www.rockefellerfoundation.org/report/true-cost-of-food-measuring-what-matters-to-transform-the-u-s-food-system/

Nasirian, F. & Menichetti, G. Molecular interaction networks and cardiovascular disease risk: the role of food bioactive small molecules. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 43, 813–823 (2023).

Adams, J. Rebalancing the marketing of healthier versus less healthy food products. PLoS Med. 19, e1003956 (2022).

Shaw, S. C., Ntani, G., Baird, J. & Vogel, C. A. A systematic review of the influences of food store product placement on dietary-related outcomes. Nutr. Rev. 78, 1030–1045 (2020).

Shepherd, R. Resistance to changes in diet. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 61, 267–272 (2002).

Kelly, M. P. & Barker, M. Why is changing health-related behaviour so difficult? Public Health 136, 109–116 (2016).

Barabási, A. L., Menichetti, G. & Loscalzo, J. The unmapped chemical complexity of our diet. Nat. Food 1, 33–37 (2020).

Menichetti, G., Barabasi, A.-L. & Loscalzo, J. Decoding the Foodome: molecular networks connecting diet and health. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 44, 257–288 (2024).

Davidou, S., Christodoulou, A., Frank, K. & Fardet, A. A study of ultra-processing marker profiles in 22,028 packaged ultra-processed foods using the Siga classification. J. Food Compos. Anal. 99, 103848 (2021).

Menichetti, G. & Barabási, A.-L. Nutrient concentrations in food display universal behaviour. Nat. Food 3, 375–382 (2022).

Hooton, F., Menichetti, G. & Barabási, A. L. Exploring food contents in scientific literature with FoodMine. Sci. Rep. 10, 16191 (2020).

Chatterjee, A. et al. Improving the generalizability of protein-ligand binding predictions with AI-Bind. Nat. Commun. 14, 1989 (2023).

Seabold, S. & Perktold, J. Statsmodels: Econometric and statistical modeling with Python. In Proc. 9th Python in Science Conference (eds van der Walt, S. & Millman, J.) 57–61 (2010).

Huber, P. J. Robust regression: asymptotics, conjectures and Monte Carlo. Ann. Stat. 1, 799–821 (1973).

Croux, C. & Rousseeuw, P. J. Time-efficient algorithms for two highly robust estimators of scale. In Computational Statistics, 411–428 (Springer, 1992).

Brown, G. G. & Rutemiller, H. C. Means and variances of stochastic vector products with applications to random linear models. Manag. Sci. 24, 210–216 (1977).

Beel, J., Gipp, B., Langer, S. & Breitinger, C. Research-paper recommender systems: a literature survey. Int. J. Digit. Libr. 17, 305–338 (2016).

Substances Added to Food (FDA, accessed 1 November 2021); https://www.hfpappexternal.fda.gov/scripts/fdcc/index.cfm?set=FoodSubstances

Substances Added to Food (FDA, accessed 1 November 2021) (2003); https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfcfr/CFRSearch.cfm?CFRPart=172

Acknowledgements

We thank D. Shanbhag at Northeastern University for his help on data collection and cleaning. We thank D. Koshkina for help in designing the figures. A.-L.B. is partially supported by National Institutes of Health grant 1P01HL132825, American Heart Association grant 151708 and European Research Council grant 810115-DYNASET. G.M. is supported by National Institutes of Health/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute K25HL173665 and American Heart Association 24MERIT1185447.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.M., B.R. and A.-L.B. conceived and designed the research. B.R. performed data collection, data modelling, statistical analysis, and data querying and integration and contributed to the writing of the manuscript. G.I. and M.S. performed data cleaning, data curation, code cleaning and optimization, and fact checking and contributed to the writing of the manuscript. P.M. performed data cleaning and data integration and contributed to the writing of the manuscript. G.M. and A.-L.B. wrote the manuscript and contributed to the conceptual and statistical design of the study.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

A.-L.B. is the founder of Scipher Medicine and Naring Health, companies that explore the use of network-based tools in health and food, and Datapolis, which focuses on urban data. All other authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Food thanks Luca Pappalardo and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figs. 1–18, Table 1 and Discussion.

Source data

Source Data Figs. 1–6

Raw data.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Ravandi, B., Ispirova, G., Sebek, M. et al. Prevalence of processed foods in major US grocery stores. Nat Food 6, 296–308 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43016-024-01095-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43016-024-01095-7