In 2017, a Republican-controlled Congress passed a package of sanctions on Russia in retaliation for its interference in the previous year’s election. The bill was approved by overwhelming margins: 419-3 in the House, 98-2 in the Senate. President Trump, the Washington Post later reported, was apoplectic over the vote and contemplated a veto, only to be eventually persuaded that he would look weak when Congress overrode it. Instead, he signed the bill without the normal ceremony while criticizing it as “unconstitutional.”

This is a measure of how deeply isolated and weird Trump’s views on Russia were within his party at the time. Trump has consistently flattered Russia, touted its economic possibilities, and disparaged the alliances arrayed against it. Whatever the basis of his beliefs on the subject — whether from frank admiration of Vladimir Putin’s authoritarianism, the praise he has received from Russians since the 1980s, or his business dealings — sympathy toward Russia is one of the few policy principles from which he has never wavered. At a closed-door meeting in 2016, Kevin McCarthy told Paul Ryan, “There’s two people I think Putin pays: Rohrabacher and Trump.” Dana Rohrabacher was a gadfly in the House mocked for his idiosyncratic Russophilia; Republicans saw Trump the same way.

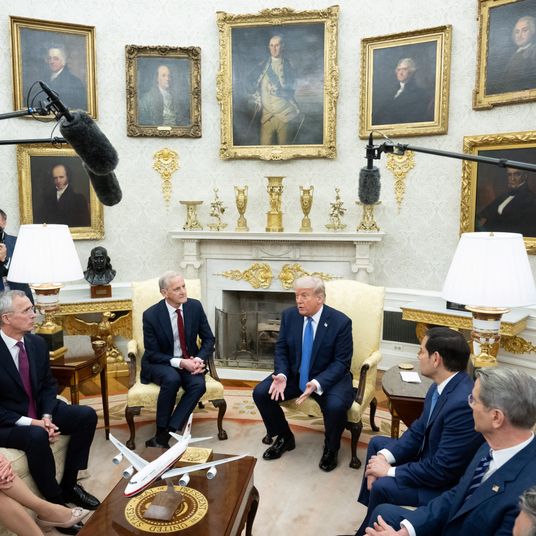

In 2024, the picture looks very different. The faction of Republicans willing to align themselves with Trump on Russia has swelled to the point where House Speaker Mike Johnson refuses to allow a vote on Ukraine aid. The Ukrainian military is starved of ammunition and retreating, NATO is contemplating its own mortality, and Europe is trembling at the prospect of future Russian aggression, which Trump says he would encourage. But his admiration of Putin no longer renders him strange or suspect within the party. Increasingly, the hawks are cast as oddballs. The metamorphosis Trump wrought through sheer force of personality may ultimately be the most globally significant ramification of his political career.

Trump’s apologists like to claim that “Trump, and his administration, have actually been tougher on Russia than many of his predecessors,” as Byron York of the Washington Examiner put it. But this is a half-truth at best. Trump spent his presidency prying apart the western alliance. He repeated a series of bizarre pro-Moscow claims — insisting, for example, that the NATO treaty committed the U.S. to backing the “very aggressive” Montenegro in a war on Russia — and refused to condemn any of Putin’s crimes. When Russian opposition leader Alexei Navalny was poisoned by a rare nerve agent in 2020 and every western intelligence agency blamed the obvious suspect, Trump demurred, “I think probably China, at this point, is a nation that you should be talking about much more so than Russia because the things that China is doing are far worse if you take a look at what’s happening with the world.”

As a matter of substantive policy, the U.S. doctrine of containing Russia, a matter of bipartisan consensus since Harry Truman, persisted throughout Trump’s presidency despite his objections. This was largely because when Trump took office, his viewpoint on Russia was so beyond the pale that there was almost nobody who shared it who could staff his administration. Trump’s one Russia-friendly choice, General Michael Flynn, who was fêted by Putin at a Moscow banquet in 2015, had to resign his position as national security adviser almost immediately because he had lied to the FBI about a meeting with the Russian ambassador. By default, Trump found himself surrounded by traditional Republican hawks who thwarted his impulses. The first Trump impeachment concerned his efforts to outmaneuver those hawks by holding up aid to Ukraine.

But during his time in office and after, Trump managed to create, from the grassroots up, a Republican constituency for Russia-friendly policy. The GOP base processes every political event as a contest of tribal loyalty. Once Trump had signaled that friendliness to Russia was a form of fealty to himself, his voters began demanding that their elected leaders and media personalities follow suit.

These displays have ranged from mocking Volodymyr Zelenskyy’s wardrobe and sneering at the Ukrainian flag to outright praise and support for Putin. The competition has run especially fierce in the conservative infotainment sphere, which is the most sensitive to audience approval. That competition is what drove Tucker Carlson to travel to Russia in February to interview Putin, who treated him to a discursive Russian-history lecture justifying his invasion of Ukraine. Carlson also broadcast ludicrous propaganda from Moscow grocery stores presenting Russia, which has a GDP per capita less than one-fifth the American level, as a thriving oasis of prosperity Americans ought to envy.

Conservatives vying to be the Trumpiest of them all have realized that supporting Russia translates in the Republican mind as a proxy for supporting Trump. Hence the politicians most willing to defend his offenses against democratic norms — Marjorie Taylor Greene, Jim Jordan, Tommy Tuberville, Mike Lee, J. D. Vance — hold the most anti-Ukraine or pro-Russia views. Conversely, the least-Trumpy Republicans, such as Mitch McConnell and Mitt Romney, have the most hawkish views on Russia. The rapid growth of Trump’s once-unique pro-Russia stance is a gravitational function of his personality cult.

One consequence of this development is the convergence of Republican Party messaging with Russian propaganda. The GOP has spent the past four years repeating a Russian-invented story that Joe Biden as vice-president had pushed to fire a Ukrainian prosecutor in order to protect the energy company Burisma, which had hired his son Hunter. (Biden was actually urging Ukraine to install a tougher prosecutor in accordance with the position advocated by democracy advocates inside and outside Ukraine.) An allegation by an FBI informant that Biden had accepted bribes, which the FBI now charges was a lie influenced by Russian intelligence, was hyped up by Republicans including former attorney general William Barr and Representative James Comer and formed the basis of an effort to impeach the president.

Putin has labeled Trump’s legal travails “the persecution of a political rival for political reasons,” echoing the GOP line. Trump, in keeping with his reluctance to admit Russian guilt, has refused to condemn Navalny’s sudden death in a remote Arctic prison, deflecting questions about his suspicious demise by depicting himself as a similarly persecuted dissident.

There is an apparent contradiction here. If Trump is likening himself to Navalny, wouldn’t that imply that Navalny was innocent and therefore Putin had done something wrong? But the paradox is resolved when you realize that Trump considers guilt or innocence totally irrelevant to the operations of any justice system. Corruption is inevitable, and the question is not whether it can be made “fair” but simply who will be locking up whom. As Carlson said shortly after his Russia trip, “Leadership requires killing people.”

Republicans withholding aid to Ukraine originally claimed it would divert resources from securing the southern border. But when hawks like McConnell dutifully negotiated a border-security bill, the pro-Russia Republicans immediately said it wasn’t good enough. They now claim funding Ukrainian defense merely prolongs the war, as if the invaded party were the one clinging to unreasonable demands. Putin has made clear that his aim is to strip Ukraine of its sovereignty and restore the puppet state that existed before the Maidan protests in 2014, a goal Republicans won’t openly endorse but seem intent on letting him fulfill. After eight years of Trump and Putin working hand in hand, they have chosen a side and they plan to see it through to victory.