ST. LOUIS — After spending nearly two years and $1.2 million switching to a new system for reporting crime, a full picture of crime trends in St. Louis city remains inconsistent — and the national picture isn’t much clearer.

After achieving state certification of its new system last fall, St. Louis stopped sending crime data to the state for eight months. The pause, which appears to have violated state law, resulted in the FBI publishing incorrect annual crime numbers for St. Louis in two of its national publications for 2021. The bureau acknowledged the errors recently after a Post-Dispatch review of state and FBI data found the totals appeared to be up to 15% too low.

The incorrect data for St. Louis comes as experts nationally express alarm about decreased police participation in the FBI’s uniform crime reporting program in 2021. That was the first year the bureau required police to switch to a different way of tracking crime called the National Incident-Based Reporting System, or NIBRS.

People are also reading…

- Former Blues president, Cardinals executive Mark Sauer dies

- Mowers, jewelry, bikes: How St. Louis police caught one of city’s most prolific thieves

- Death threats target St. Louis emergency management chief after tornado siren fails

- St. Louis to get National Guard help, tells Ameren to disconnect power in unsafe buildings

The change was intended to give a more complete picture of crime across the country by capturing greater detail on incidents, victims and offenders. But police agencies have struggled to make the switch, leaving enormous gaps in the data-gathering effort.

“We need reliable crime data to evaluate the claims made by politicians, policymakers and others,” said Richard Rosenfeld, a criminologist at the University of Missouri-St. Louis, who noted that political rhetoric on crime has been heating up ahead of the midterm election. “We need reliable data to replace guesses and baseless opinions.”

The FBI and Bureau of Justice Statistics have provided $120 million in federal funding to bolster state and local NIBRS transitions, including a $1.2 million grant for St. Louis.

Despite that, more than 7,000 out of nearly 19,000 law enforcement agencies nationwide failed to submit any crime data in 2021, and only 52% of agencies submitted a full year’s worth, according to the FBI. It’s a massive decline from previous years, when the FBI still accepted data in the previous “summary” format.

“We used to have 95%-97% of agencies reporting,” said Jeff Asher, a data analyst and cofounder of AH Datalytics. “We’re probably talking about maybe 2024 or 2025 before reporting reaches where we were previously.”

The FBI counted St. Louis among fully reporting agencies, but it should not have, because the department had submitted only 11 months of crime data for 2021 before the FBI’s March deadline, an FBI spokesperson confirmed.

The long pause in reporting, St. Louis police said, was partially to address new issues that arose with the reporting of justifiable homicides — cases where investigators determine no one is criminally liable in a killing, for reasons including self-defense.

With data missing or incomplete for thousands of agencies — including the nation’s two largest departments, New York and Los Angeles — the FBI and the Bureau of Justice Statistics resorted to using “well-established estimation techniques” to fill in the gaps in the 2021 national report.

The FBI itself is cautioning against comparing the estimated 2021 crime rates with previous years, said Rosenfeld.

“That means the most basic question we can ask of any given year’s crime data — Did crime go up or down? — can’t be answered by the 2021 NIBRS data.”

“This was an avoidable problem,” Rosenfeld said.

He noted that the FBI could have changed course and allowed agencies to keep using the old system in parallel with NIBRS, once it became that clear thousands of agencies would not meet the transition deadline.

“That would have eliminated or greatly reduced the need to estimate,” he said, “and we would have more reliable crime data.”

The first of three shooting victims is taken out of the Clinton Peabody public housing complex in the 1400 block of Chouteau Avenue, passing by the memorial to another man who was shot and killed at the same site the year before, on Monday, Feb. 14, 2022 in the Peabody Darst Webbe neighborhood.

FBI slip-up

St. Louis’ decision to delay reporting data for December 2021 until well past the FBI’s March deadline exposed a flaw in the FBI’s protocols for processing crime data. It also caused the bureau to publish inaccurate 2021 figures for the city.

Before the Oct. 5 release of the FBI’s 2021 NIBRS publications, local and state officials acknowledged to the Post-Dispatch that St. Louis submitted data covering the first 11 months of 2021, then stopped reporting for months — even though state law requires police to report data to the Missouri Highway Patrol, the state’s collector of crime data.

St. Louis then didn’t resume reporting until September 2022, marking an eight-month delay.

Though St. Louis didn’t submit any new data in December, it did submit two corrections to previous submissions. Those corrections, according to a statement from the FBI’s UCR Program, “triggered the system to acknowledge participation for that month.”

Because the FBI’s system accepted St. Louis as having participated for a full year, the bureau published the city’s data in the agency tables for its “Crime in the United States” and “National Incident-Based Reporting System” publications for 2021, despite the bureau’s policy to exclude agencies that report less than 12 full months of data.

The FBI’s unexpected inclusion of St. Louis in its publications on Oct. 5 led a Post-Dispatch reporter to compare those totals with the data in the Highway Patrol’s “ShowMeCrime” portal. The FBI’s totals were up to 15% lower.

“Upon further review, it was not a full 12 months complete submission,” the FBI told the newspaper.

Because the publications have already been disseminated, the bureau said, it does not plan to correct them, but it intends to prevent similar errors in future publications by developing algorithms to “detect this type of anomaly and count the months with the anomaly as incomplete.”

“It’s a new system, so it’s not shocking” to see a hiccup like this, said Asher, the data analyst. “But I think it reflects the challenge of switching to NIBRS.”

Challenges in the rollout

St. Louis’ transition from the FBI’s old “summary” style of reporting crime to the NIBRS standard has taken longer and been more challenging than hoped, police officials acknowledge.

The FBI launched its uniform crime reporting program in 1930. Agencies across the U.S. voluntarily reported crime totals to the FBI in “summary” format, either directly or through a state program, using standardized definitions of major offense types like murder or burglary. Over decades, the system achieved wide adoption and reliability, and it remained relatively unchanged.

But the system had shortcomings. In 1988, the FBI launched a new reporting system, NIBRS, designed to capture more details, such as the age, sex and race of victims and the circumstances of the crimes. For decades, the FBI allowed police departments to report using either system. Then in 2015, the FBI announced it would retire the old summary system in 2021 and agencies would be required to transition to using NIBRS.

St. Louis got started by securing a federal grant to pay for a new NIBRS-compliant records management system. One early project timeline called for St. Louis to be reporting NIBRS data to the state by September 2020. But the pandemic intervened.

“It shut down a lot of things in the agency for almost a year and a half,” said Maj. Eric Larson, commander of support operations.

When the department’s new records system came online in December 2020, there were problems from the start. For months, the department was unable to post statistics publicly on its website or to submit data to the patrol without errors.

The Post-Dispatch highlighted the early problems in a June 2021 story. Soon after, the department began posting basic neighborhood and citywide crime totals on its website. But the detailed NIBRS submissions to the Highway Patrol remained problematic.

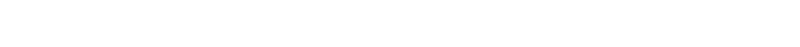

Throughout 2021, the city worked with its vendor, Optimum Technologies, to resolve various bugs in the new system. Finally, on Sept. 15, 2021, St. Louis successfully submitted its first batch of NIBRS files, prompting Kyle Comer, manager of the state’s Uniform Crime Reporting program at the time, to notify the St. Louis Metropolitan Police Department that he had certified St. Louis as NIBRS compliant.

“I know your agency has worked very hard to achieve NIBRS/MIBRS compliant status,” Comer wrote in a congratulatory email, obtained later by the Post-Dispatch through an open records request.

But Comer also warned that “many more data submissions are expected” for St. Louis to fully cover all the crime and arrests that had occurred since Jan. 1, 2021.

Indeed, because it had taken St. Louis so long to submit any data for 2021, the FBI omitted the city from its first three quarterly crime reports for the year. But after further submissions in November, St. Louis was added back for the FBI’s fourth-quarter report.

It seemed like progress. In fact, Stephanie Vert, who replaced Comer at the Highway Patrol, later told the Post-Dispatch that because St. Louis had completed the NIBRS testing phase, the patrol was no longer monitoring St. Louis’ compliance.

But St. Louis had not submitted numbers covering December 2021 — and it didn’t for eight more months. The department blew past the FBI’s March deadline for inclusion in its 2021 national crime publications, and again the FBI omitted St. Louis from its quarterly crime reports. Throughout this time, though, the department continued to post basic crime totals on its website.

The NIBRS logjam finally broke on Sept. 9, when St. Louis sent the long-delayed December 2021 data. Two weeks later, it caught up on submissions for 2022.

St. Louis police Officer Velvet McElroy embraces Leslie Byrd at the funeral for Byrd’s son, JaDun Byrd, at Williams Temple Church of God in Christ on March 22, 2022. JaDun, 19, was shot and killed while FaceTiming with his mother on March 2 outside the Homer G. Phillips Health Center. McElroy and Leslie Byrd know each other from Byrd’s time working in youth violence prevention at Better Family Life.

Hung up on homicides

The purpose of the eight-month delay, police officials told the Post-Dispatch, was to resolve how to correctly report justifiable homicides in NIBRS. Officials said they didn’t become aware until well after launching their new system that NIBRS requires police to create two separate reports for each justifiable homicide: one describing the criminal activity of the person killed and another describing the killing itself.

“We have generations of officers here who have written reports where you incorporate the entire incident in a single report,” said Jerry Baumgartner, the department’s manager of planning and research.

Those officers had to be retrained, he said. The department’s homicide staff also had to go back through each instance of justifiable homicide for 2021 and “disentangle” the single report into the required two.

Police admit to being particularly sensitive to public scrutiny of homicide numbers — such as a ProPublica report in March that noted St. Louis had begun classifying a greater share of killings as justifiable since 2020.

Baumgartner said officials thought it would be better to delay reporting, rather than publish crime totals that would have to be changed several months later, once the department finished addressing the justifiable homicide issues.

“We were very adamant about making sure what we submitted was true and accurate,” Baumgartner said, noting that there can be a double-edged sword when police release a number. “If we have to come back and revise that number, whether that number goes up or down, there’s always going to be some questions about it.”

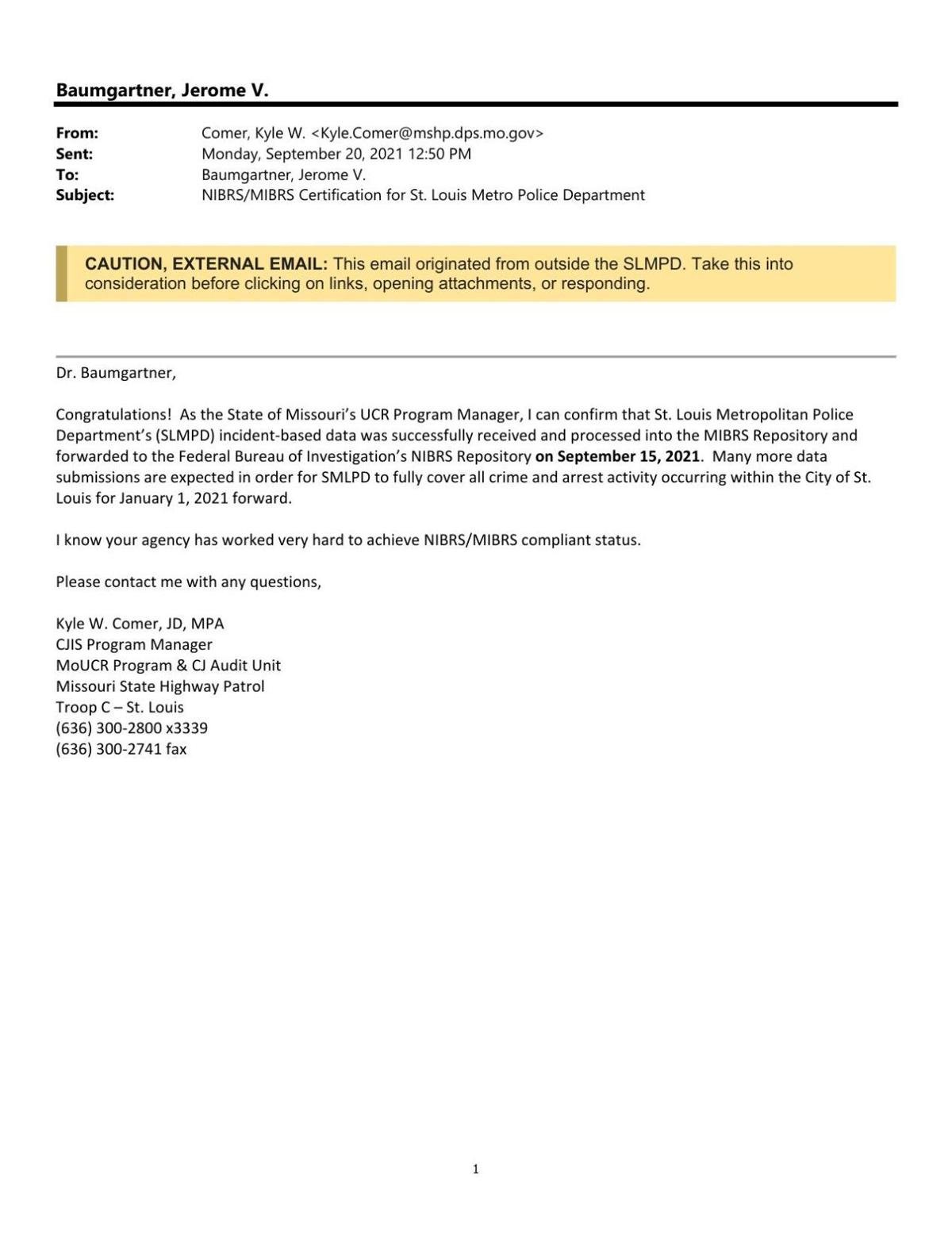

The department also used the delay to work with Optimum Technologies to resolve other technical errors related to NIBRS specifications that sometimes prevented the state from accepting a small number of crime reports, department spokesperson Evita Caldwell said this summer.

The update process can be time-consuming. And in recent months, it has required extra quality control, Baumgartner said, after some of Optimum’s fixes broke other aspects of the system.

Optimum was set to earn $81,300 from St. Louis for software maintenance and support in 2022, according to a quote sent by Optimum CEO Josh Davda in September 2021 and obtained through a records request.

Skirting penalties

Missouri law requires police agencies to submit uniform crime reports to the Highway Patrol, and the law tasks the state Department of Public Safety with overseeing this effort. The law allows DPS to penalize noncompliant agencies by withholding state and federal grant funds they otherwise would receive.

In previous years, when most agencies submitted data in the old “summary” format, DPS would enforce the penalties if agencies failed to submit monthly crime reports before a deadline. Local examples include Berkeley police and the now-defunct Wellston police, which were slapped with several small grant withholdings between 2008 and 2017.

As the NIBRS deadline drew closer, Missouri legislators amended the law in 2018 to give police a reprieve from those penalties.

The law’s grace period expired on Dec. 31, 2021, but the Department of Public Safety still awarded St. Louis two grants in June and July worth more than $110,000, even though St. Louis was at least six months behind in reporting crime data at that point.

DPS considers agencies to be out of compliance with the law if they failed to submit crime data for three months, spokesman Mike O’Connell told the Post-Dispatch by email in September. But its Grants Unit did not settle on that standard until July 20, when it was first published in a “notice of funding opportunity” for the Local Violent Crime Prevention Grant, and after St. Louis received its two grants.

Going forward, O’Connell said, the state’s online system for grant applications will prompt agencies about their ineligibility if required crime data submissions have not been made.

St. Louis police officials said they weren’t worried about penalties when they decided to stop reporting data at the end of 2021, noting the state had been a good partner, and understood the complexities St. Louis faced.

“None of this happened in a vacuum,” said Larson, the St. Louis support operations commander. “We were in contact with the state regularly throughout this whole process: where we were at, what we were doing, why we were doing it, the errors and things that we were finding.”

Shattered entry doors to the MX Movies theater on Washington Avenue in downtown St. Louis await repair on Friday, April 1, 2022, after gunfire damaged three downtown businesses the night before. A window was also shot out at the closed Pi Pizzeria nearby, and a Metrolink elevator window was also damaged.

Other departments

When the FBI announced in 2015 that it would transition to collecting only NIBRS data by 2021, it was clear it would be a major undertaking with enormous technical challenges for most agencies. In a 2018 frequently asked questions document, the FBI estimated that large and complex agencies should expect their transitions to take two years.

Rosenfeld, the UMSL criminologist, noted that the FBI did its best to support agencies across the nation by giving them six years’ notice and providing millions in grant money to help pay for expensive system upgrades. Still, some agencies put off the change, he said.

“Like students who wait until the last minute to turn in their papers, many agencies waited much too long to make the transition,” he said.

Regardless of whether St. Louis falls into that category, it’s clear that some of its peer police departments got better head starts.

Kansas City, in particular, was an early adopter of NIBRS in Missouri. The highway patrol certified Kansas City as NIBRS-compliant in 2009, more than a decade before the FBI made it mandatory.

More recently, both Kansas City and St. Louis County made significant changes to their records management systems. Kansas City replaced its Tiburon system with one from Niche Technology in 2019, while St. Louis County used a $103,875 federal grant to upgrade its own homegrown system, CARE, to make it NIBRS compliant.

At both departments, implementing the new systems required several years of work. St. Louis County’s CARE overhaul was mostly finished by mid-2019, said department spokesman Adrian Washington, which allowed the agency to spend several months testing before taking the system live in January 2020.

In contrast to St. Louis city, both Kansas City and St. Louis County were able to report crime data without interruption after obtaining NIBRS certification for their new systems from the Highway Patrol, representatives of both departments said. O’Connell, the DPS spokesman, confirmed neither had missed a submission since January 2021.

As for St. Louis, it is fully caught up on sending crime reports through September.

“All of that has improved over time,” said Baumgartner. “As you can see, we have made some good headway.”