An investigation into the Personal Financial Literacy of

Cryptocurrency users.

Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of

BACHELOR OF COMMERCE HONOURS

In

Information Systems

(FACULTY OF COMMERCE)

RHODES UNIVERSITY

by

ALYSSA SHAWNTAY WILLIAMS

2019

Department: Information Systems

Address: Rhodes University, P.O Box 94, Grahamstown, 6140

Email: g11w3735@campus.ru.ac.za

Telephone: 073 493 5444

Supervisor: Ed de la Rey

Department: Information Systems

Address: Rhodes University, P.O Box 94, Grahamstown, 6140

Email: E.delaRey@ru.ac.za

Telephone: 046 603 8375

� An investigation into the Personal Financial Literacy of Cryptocurrency users.

by

ALYSSA SHAWNTAY WILLIAMS

SUPERVISOR: MR ED DE LA REY

DEPARTMENT: DEPARTMENT OF INFORMATION SYSTEMS

FACULTY: FACULTY OF COMMERCE, RHODES UNIVERSITY

DEGREE: BACHELOR OF COMMERCE HONOURS

ABSTRACT

The purpose of the study is to determine the level of financial literacy among cryptocurrency

users. In this study, a survey instrument that included 36 items that measure constructs such as

general financial knowledge, financial behaviour, and financial attitudes was administered to

32 cryptocurrency users. The data was collected by means of convenience sampling and results

were analysed using descriptive statistics. It was found that all individual knowledge variables

had a positive impact on the financial knowledge construct. The same was observed for all

individual attitude and all individual behaviour variables which were observed to have a

positive impact on the financial attitude construct and financial behavior construct respectively.

KEY WORDS:

Personal Financial Literacy, Financial Education, Cryptocurrency, Crypto Users Digital

Money, Blockchain, Financial Knowledge, Financial Behaviour, Financial Attitude

Page 2 of 74

�ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Firstly, I would like to give thanks to GOD, for being the source of my strength, light in this

walk and giver of my ability.

I would also like to thank the following people without whom this voyage would not have been

successfully completed:

My supervisor, Mr Ed De La Rey for the way in which he supported me throughout my Honours

year. His patience and determination got me to the end.

Dr Tinashe Ndoro for his guidance with the statistical analyses.

Thank you to my Information Systems Honours classmates, especially my group members who

always strived for excellence: Mr Msimelelo, Mr James Higgs, Ms Priyal Karson, Ms Rufaro

Kanganga, and Ms Nikitha Patel.

The Rhodes University Biotechnology Innovation Centre’s academic and administrative staff,

especially Prof Janice Limson and Dr Ronen Fogel for always pushing me to take every

opportunity that came my way. Prof, you have really made me feel valued and appreciated, not

to mention I look up to you so much. Ron, thank you for teaching me the most random-awesome

information about science and the world in general. Biosensors Lab, it has been absolutely

amazing.

I would like to thank all my friends who encouraged me to always keep pushing forward. A

specific mention to my cheer team, Ms Lesleigh Titus, Mr Nicholas Dettmer, and Ms Primrose

Shakwane.

A special mention to my siblings, Ms Shannon Bianca Williams and Ms Loryn Michelle

Williams, for their unwavering efforts to always root me on and for making me such a proud

Big sister.

Dr Setshaba David Khanye, for the inspiration, willingness to hear every idea and being by my

side every step of the way.

Finally, to a woman like no other, Rashica Williams, for inspiring me to be a strong,

independent, selfless woman.

~Abundantly Blessed, Favoured and Protected~

Page 3 of 74

�DECLARATION

I Alyssa Shawntay Williams, hereby, on this 21st day of October 2019, declare that:

The work in this thesis is my own work.

All sources used or referred to have been documented and recognised.

This thesis has not previously been submitted in full or partial fulfilment of the

requirements for a qualification.

I am fully aware of Rhodes University’s policy on plagiarism and I have taken every

precaution to comply with the regulation.

Ethics clearance Review Reference number for this research project is 2019-0742-828

____________________

Alyssa Shawntay Williams

Page 4 of 74

�TABLE OF CONTENTS

List of Tables .............................................................................................................................. 7

List of Figures ............................................................................................................................ 7

Chapter One: Research Overview .............................................................................................. 8

1.1 Introduction .............................................................................................. 8

1.2 Goals of the Research ............................................................................ 10

1.3 Methods, Procedures, Techniques and Ethical Consideration ............... 11

Chapter Two: Financial Literacy.............................................................................................. 12

2.1 Introduction ............................................................................................ 12

2.2 Definition of Financial Literacy ............................................................ 12

2.3 Importance of Financial Literacy ........................................................... 13

2.4 Financial Literacy Studies ..................................................................... 15

2.5 Summary ................................................................................................ 17

Chapter Three: Cryptocurrency ................................................................................................ 18

3.1 Introduction ............................................................................................ 18

3.2 Blockchain ............................................................................................. 19

3.3 Cryptocurrency ...................................................................................... 19

3.4 Evolution/Emergence of Cryptocurrency .............................................. 20

3.5 Role of Cryptocurrency in Financial Markets ....................................... 22

3.6 Risks of Cryptocurrency on Global Financial Markets ......................... 24

3.7 Importance of Financial Literacy among Cryptocurrency Users ........... 26

3.8 Summary ................................................................................................ 27

Chapter Four: Methodology ..................................................................................................... 29

4.1 Introduction ............................................................................................ 29

4.2 Research Paradigm ................................................................................ 29

4.3 Research Design .................................................................................... 29

4.4 Data Gathering ....................................................................................... 29

Page 5 of 74

�4.5 Population and Sample Size .................................................................. 30

4.6 Data Analyses ........................................................................................ 30

4.7 Reliability and Validity .......................................................................... 31

4.8 Ethical Considerations ........................................................................... 31

4.9 Summary ................................................................................................ 32

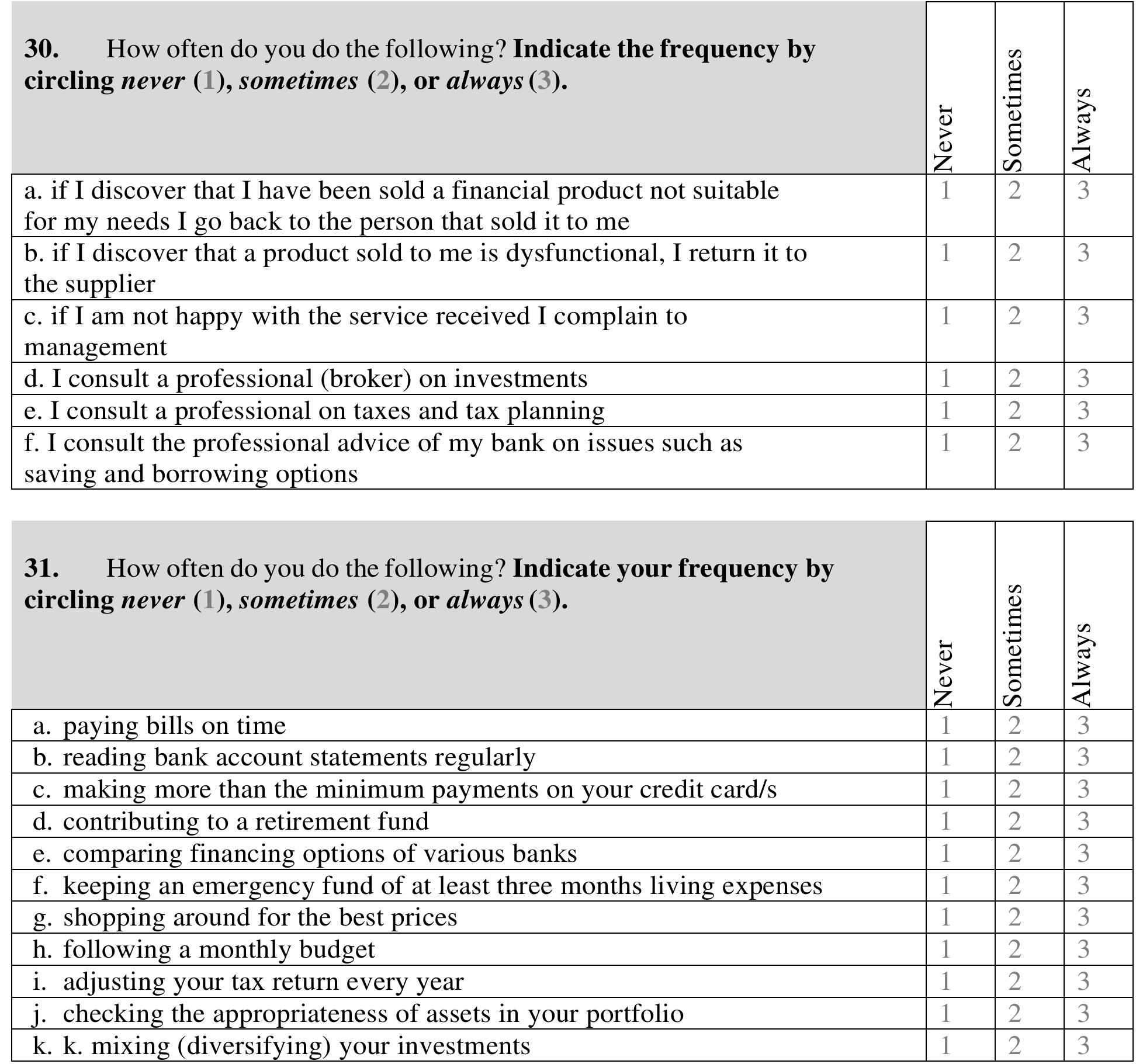

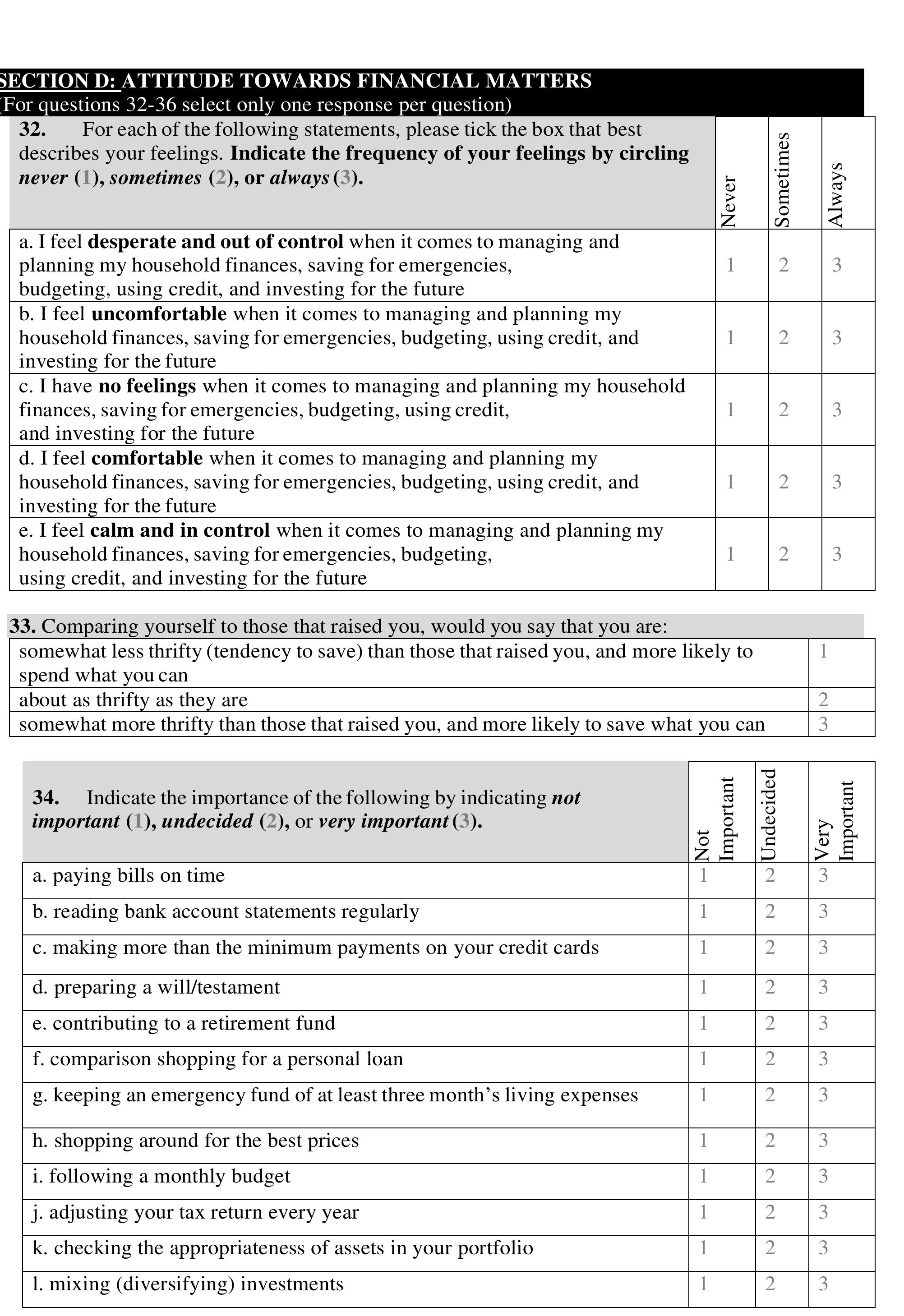

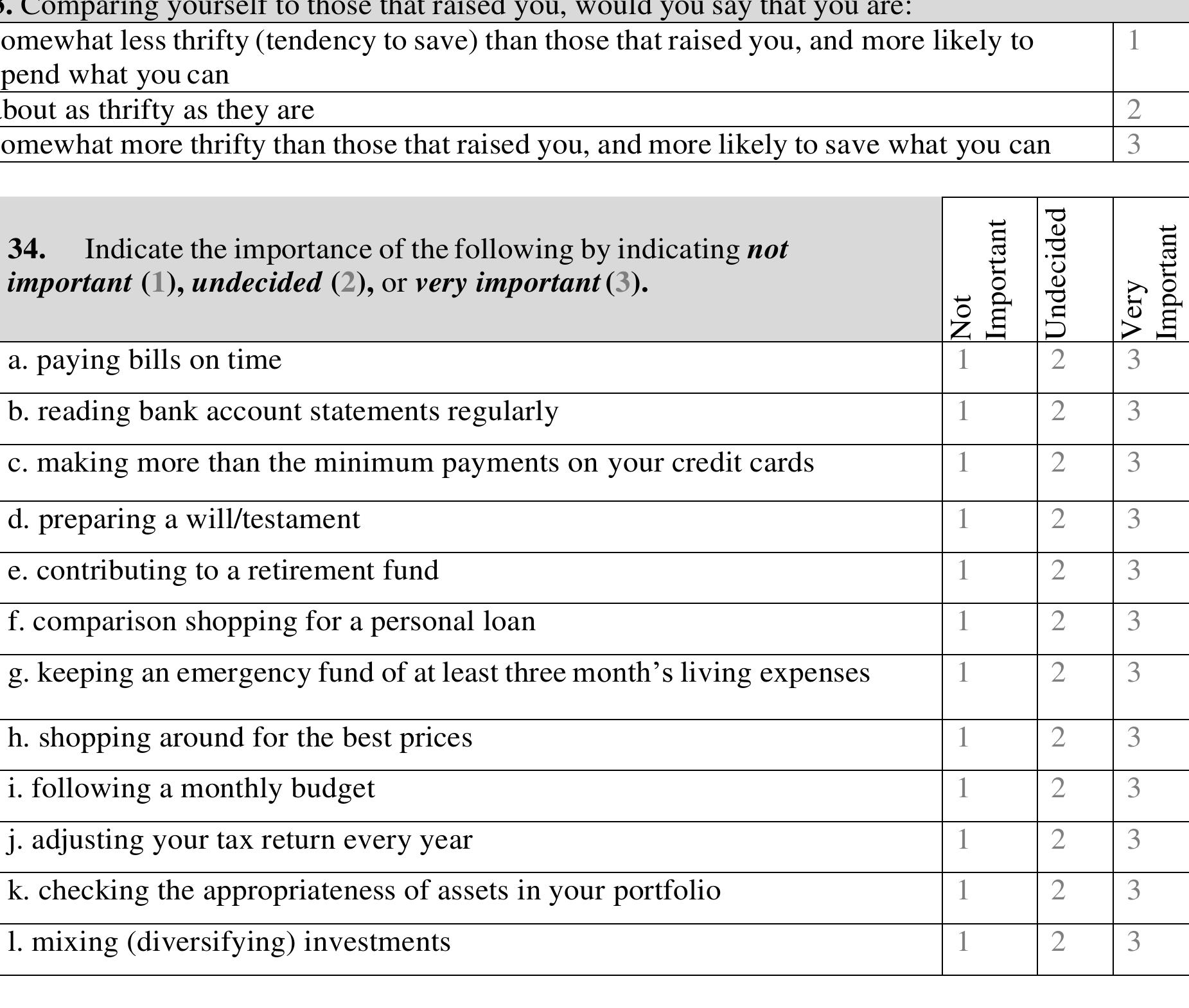

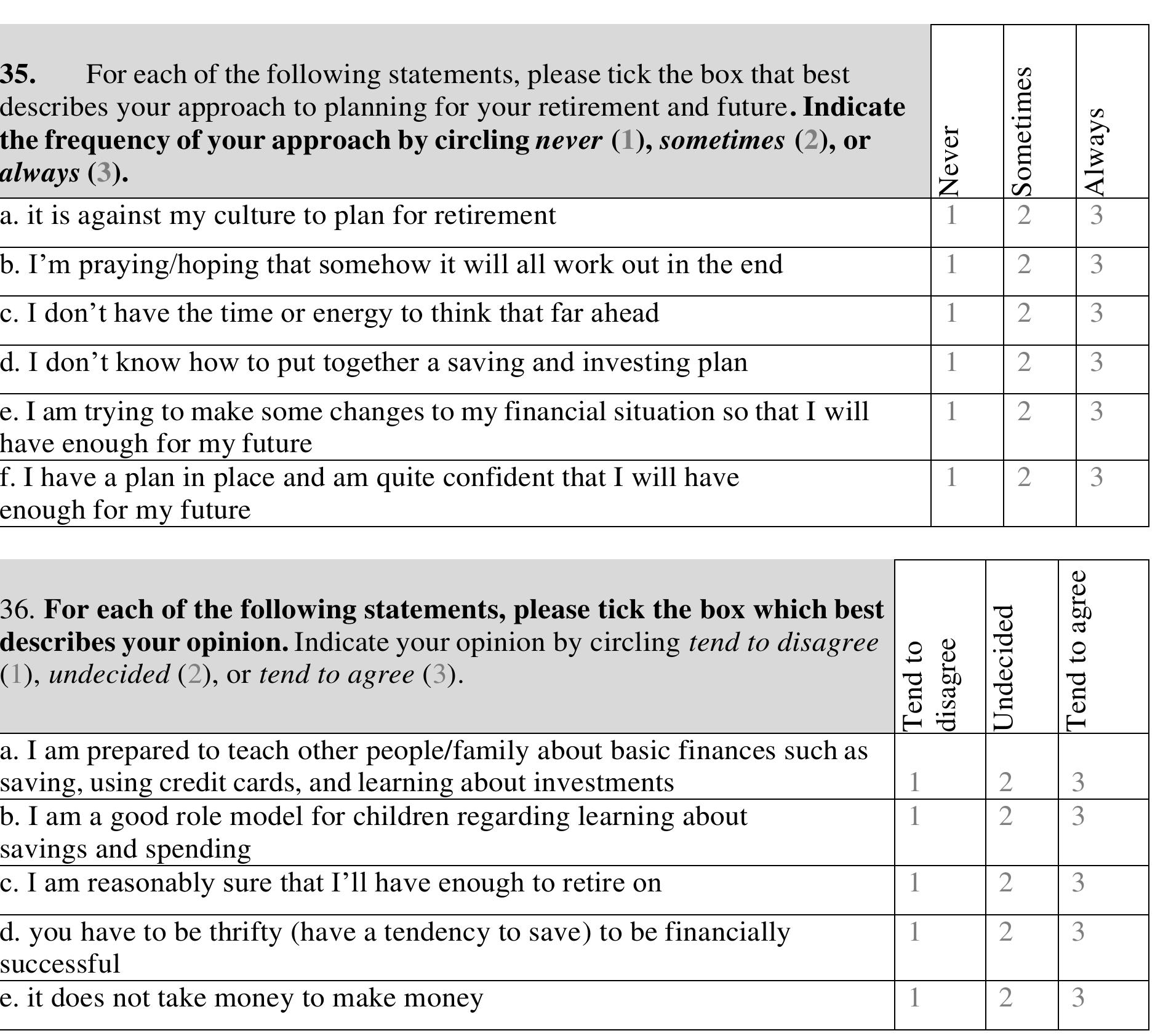

Chapter Five: Data Analysis and Results ................................................................................. 33

5.1 Introduction ............................................................................................ 33

5.2 Demographics ........................................................................................ 33

5.3 User Data ............................................................................................... 36

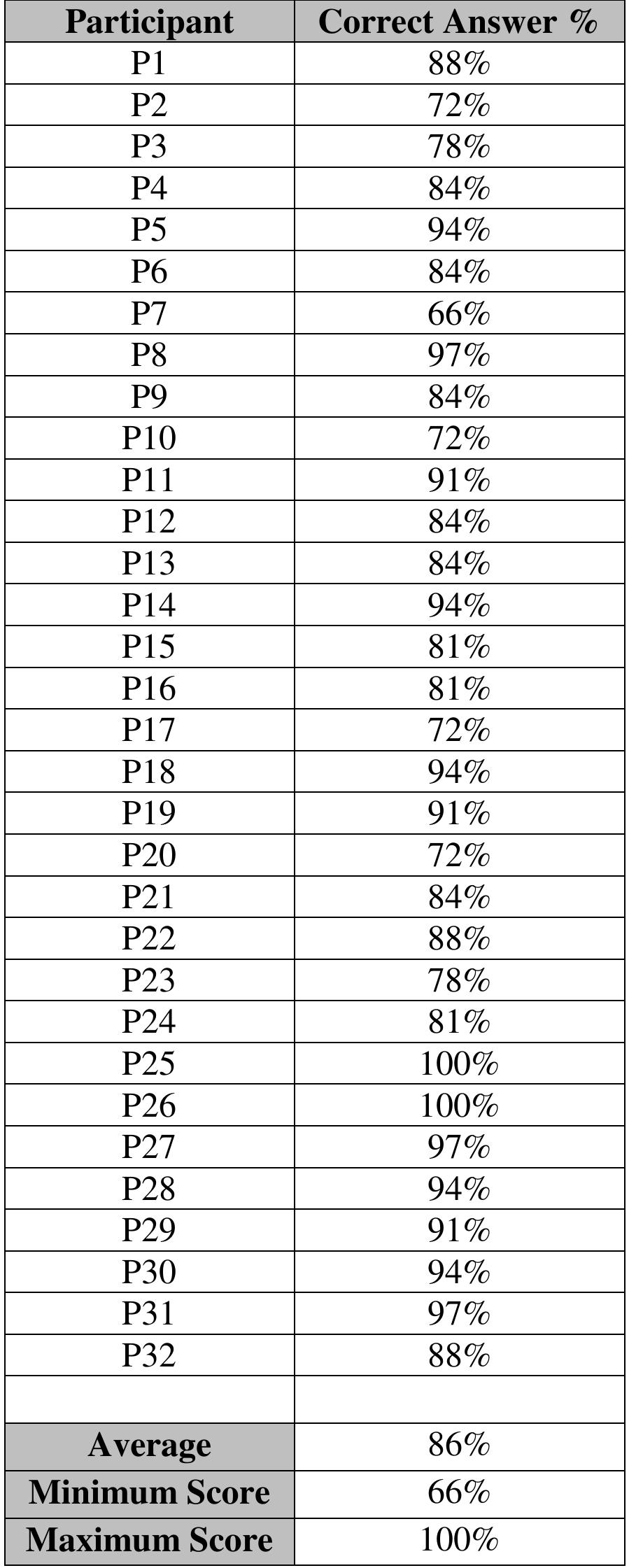

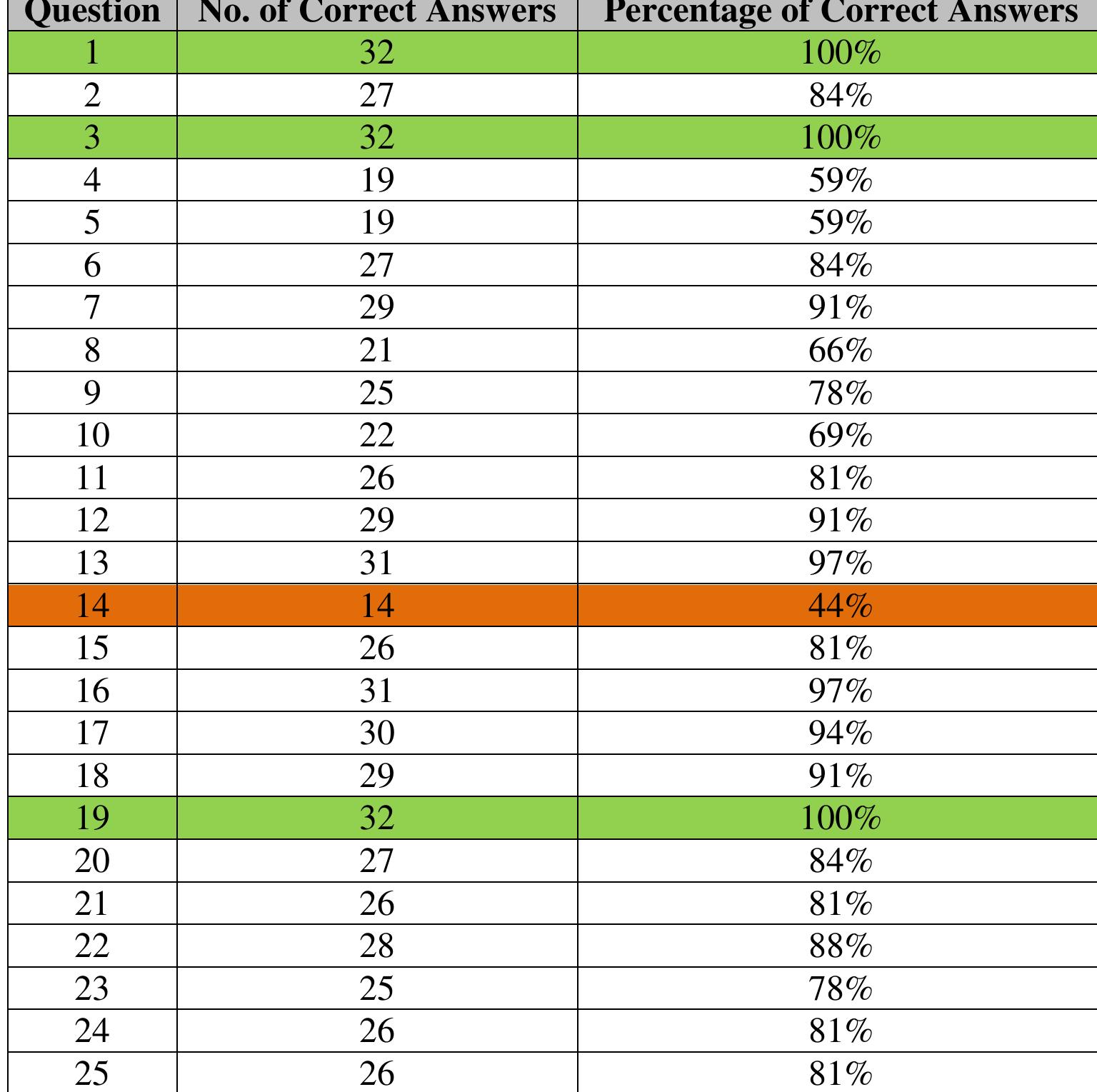

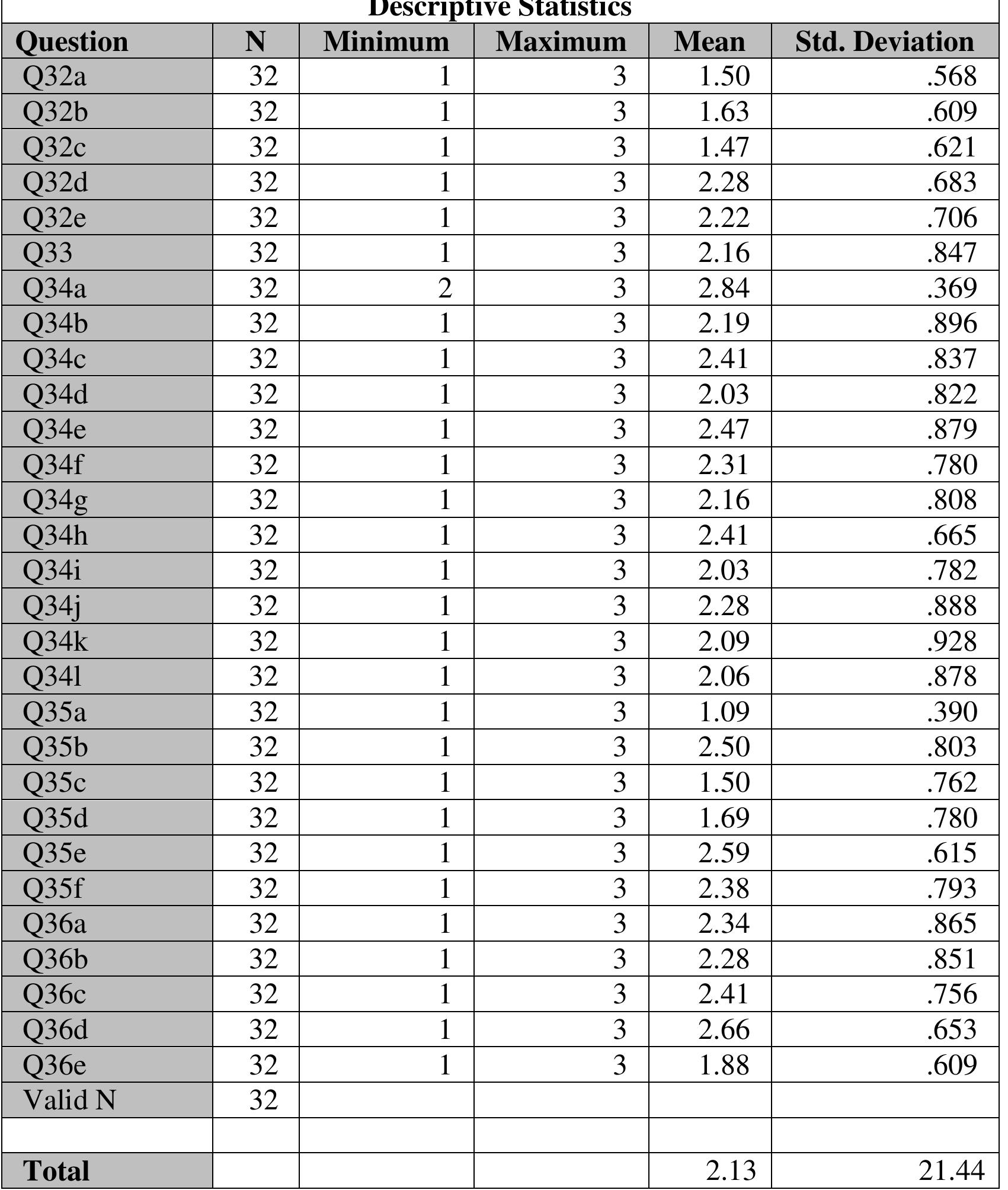

5.4 Construct 1: Financial Knowledge and Understanding ......................... 40

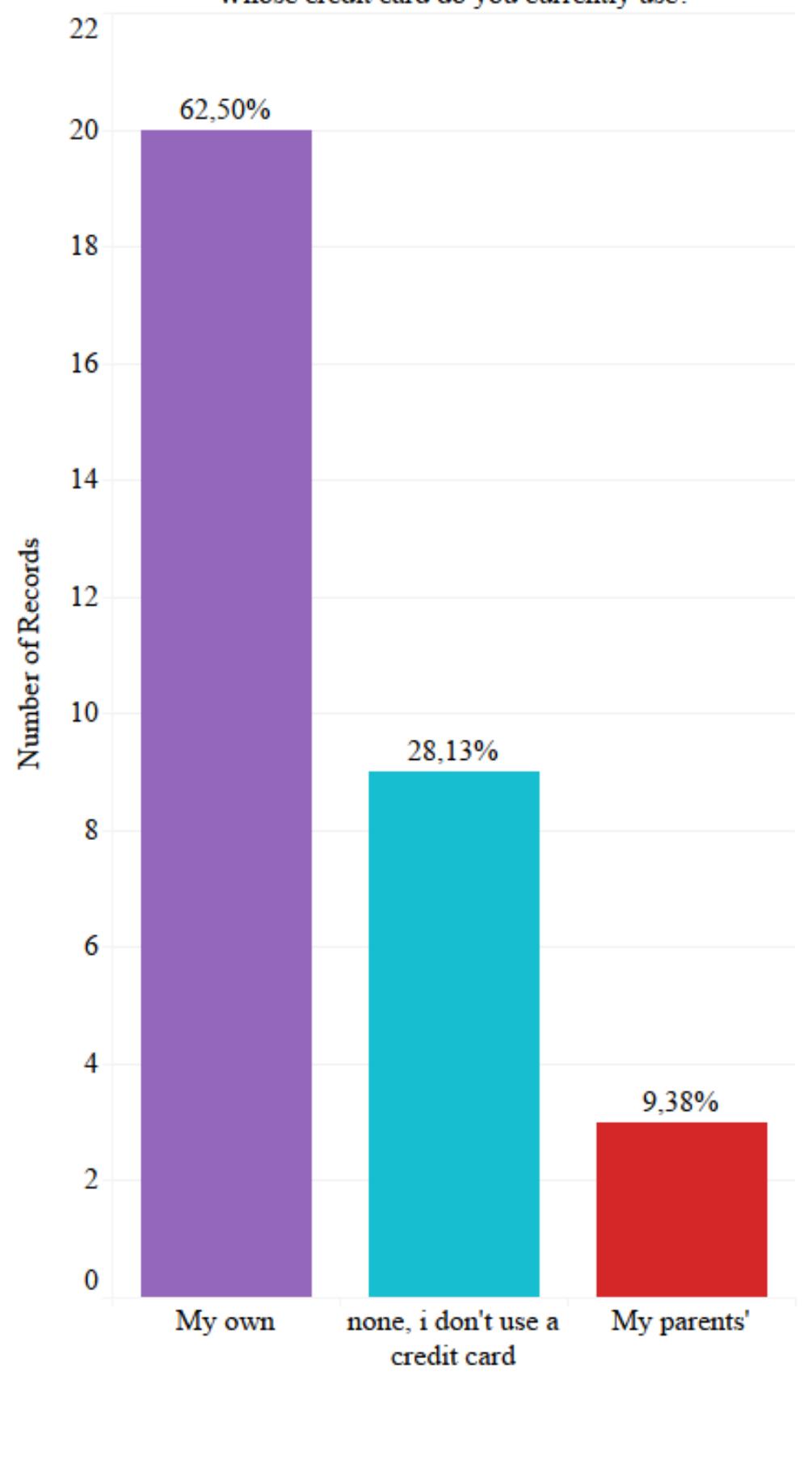

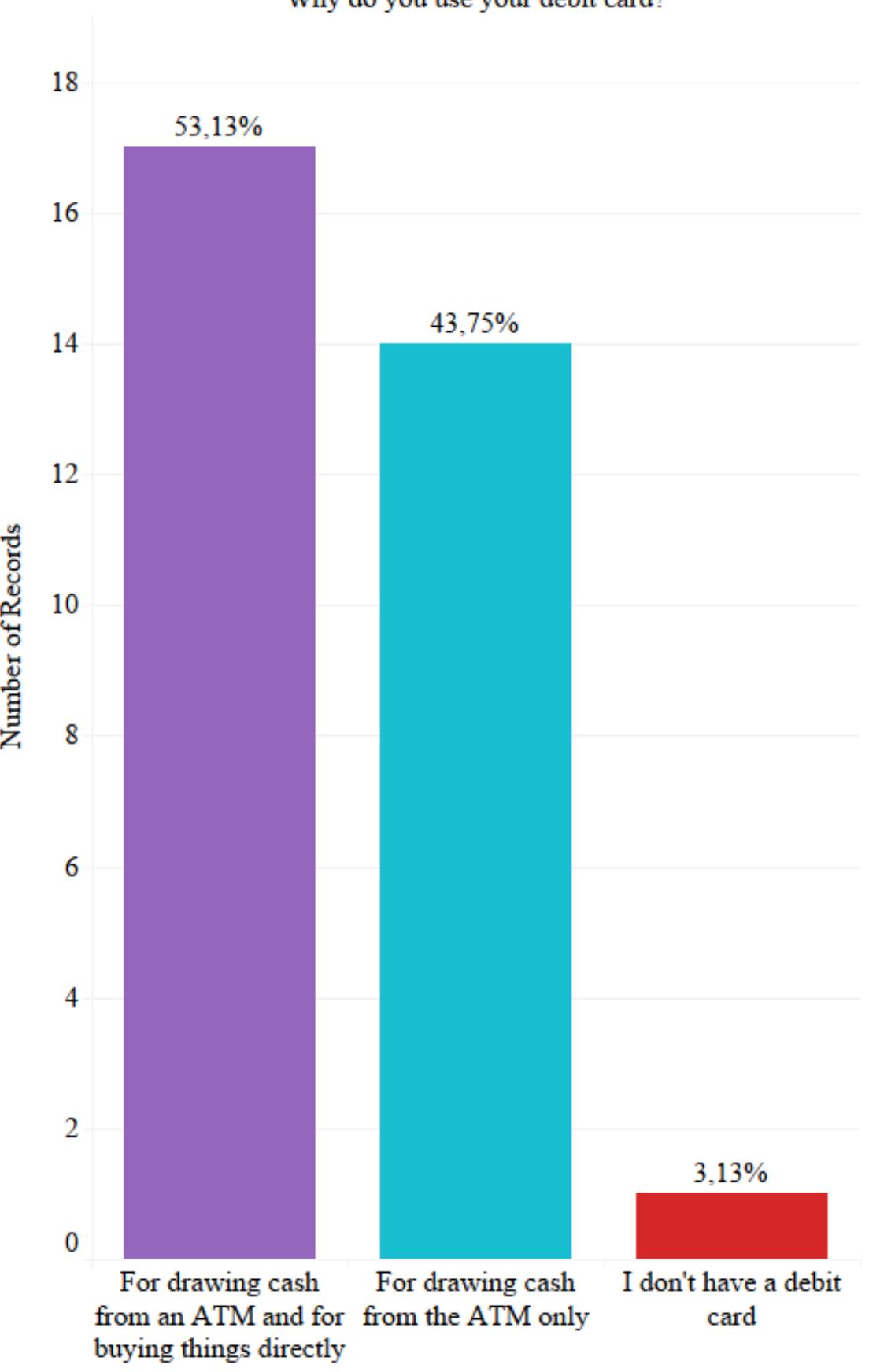

5.5 Construct 2: Financial Behaviour .......................................................... 43

5.6 Construct 3: Attitude Towards Financial Matters.................................. 47

5.7 Reliability............................................................................................... 50

5.8 Summary ................................................................................................ 50

Chapter six: Discussion and Conclusion .................................................................................. 51

6.1 Introduction ............................................................................................ 51

6.2 Discussion .............................................................................................. 51

6.3 Conclusion ............................................................................................. 53

6.4 Limitations and Future Work ................................................................. 53

References ................................................................................................................................ 55

Appendix A: Financial Literacy Questionnaire ....................................................................... 60

Appendix B: Question Matrix .................................................................................................. 68

Appendix C: Public Notice ...................................................................................................... 70

Appendix D: Individual Participation Notice........................................................................... 71

Appendix E: Informed Consent Notice .................................................................................... 72

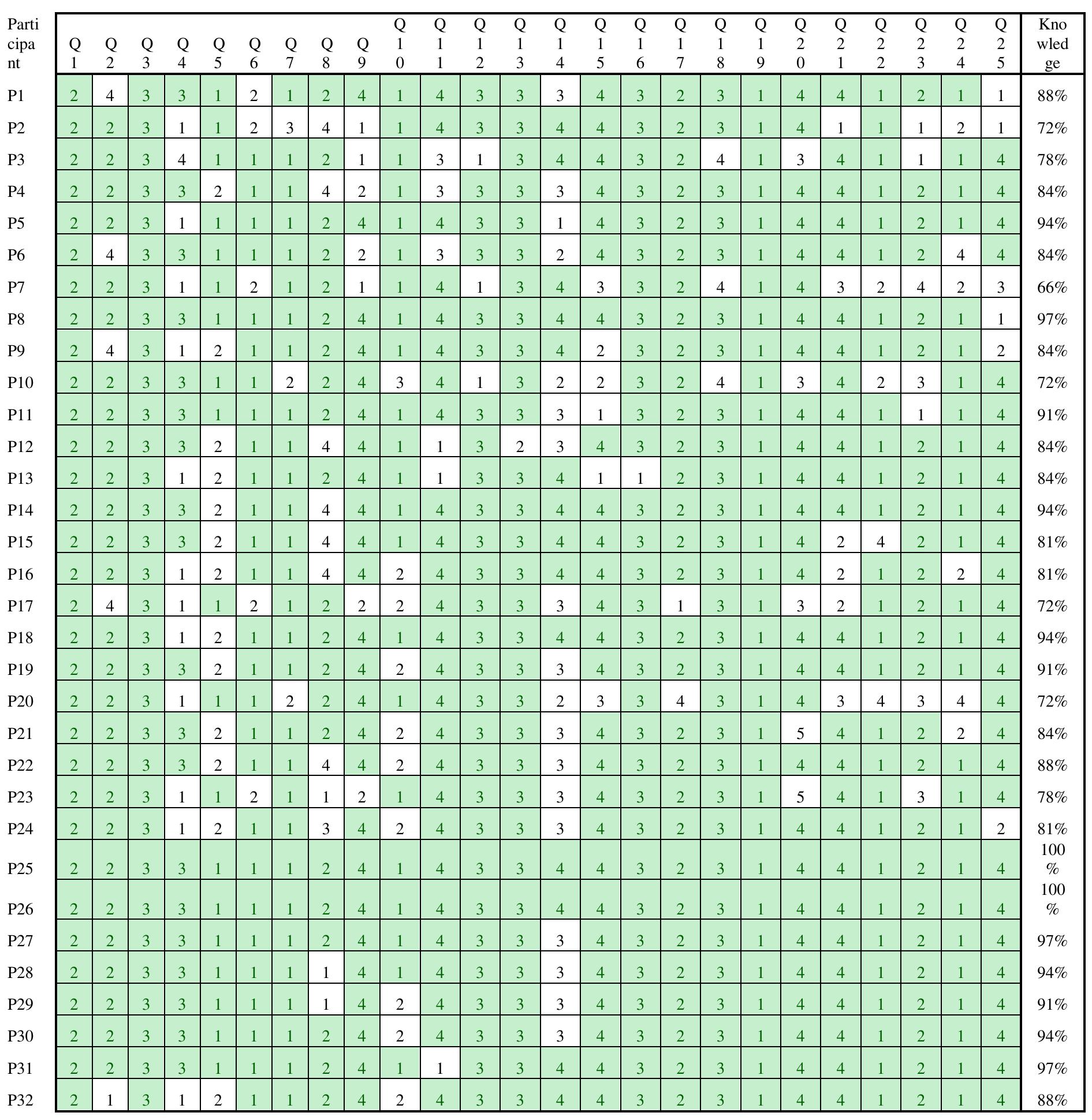

Appendix F: Knowledge Construct Dataset ............................................................................. 73

Appendix G: Turnitin Report ................................................................................................... 74

Page 6 of 74

�LIST OF TABLES

Table 1: Fiat Currency vs Cryptocurrency ............................................................................... 21

Table 2: Knowledge Construct Score Percentages .................................................................. 41

Table 3: Number of Correct Answers per Question ................................................................. 42

Table 4: Financial Behaviour Descriptive Analysis ................................................................. 47

Table 5: Financial Attitude Descriptive Analysis .................................................................... 49

Table 6: Reliability Statistics for Instrument ........................................................................... 50

LIST OF FIGURES

Figure 1: Gender of Participants .............................................................................................. 33

Figure 2: Age of Participants ................................................................................................... 34

Figure 3: Nationality of Participants ........................................................................................ 35

Figure 4: Highest Qualification obtained by Participants ........................................................ 35

Figure 5: How many users Purchase Cryptocurrencies ........................................................... 36

Figure 6: How many users utilise Cryptocurrencies to Purchase Goods and Services ............ 36

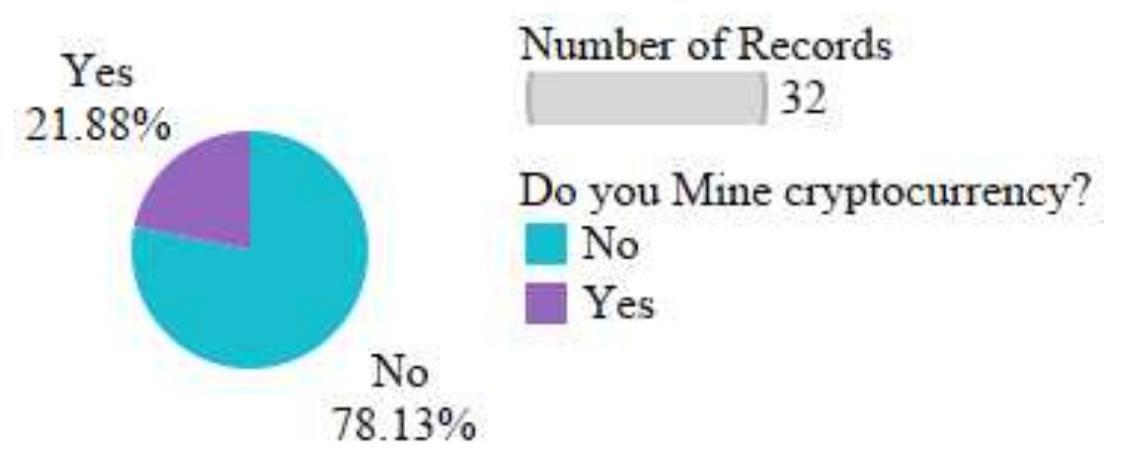

Figure 7: How many users Mine Cryptocurrencies ................................................................. 37

Figure 8: How many users Trade Cryptocurrencies................................................................. 37

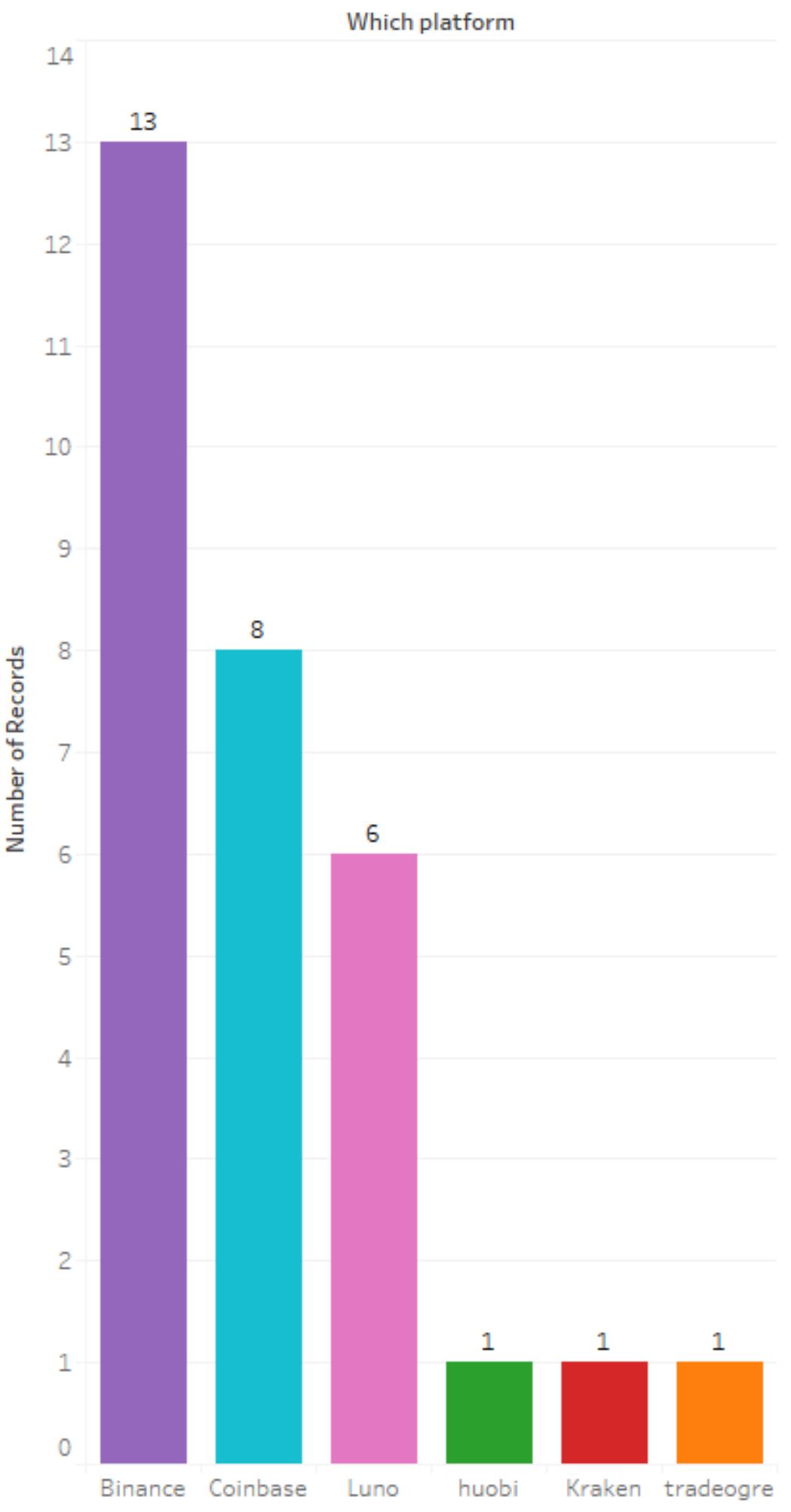

Figure 9: Which platform participants use to trade .................................................................. 38

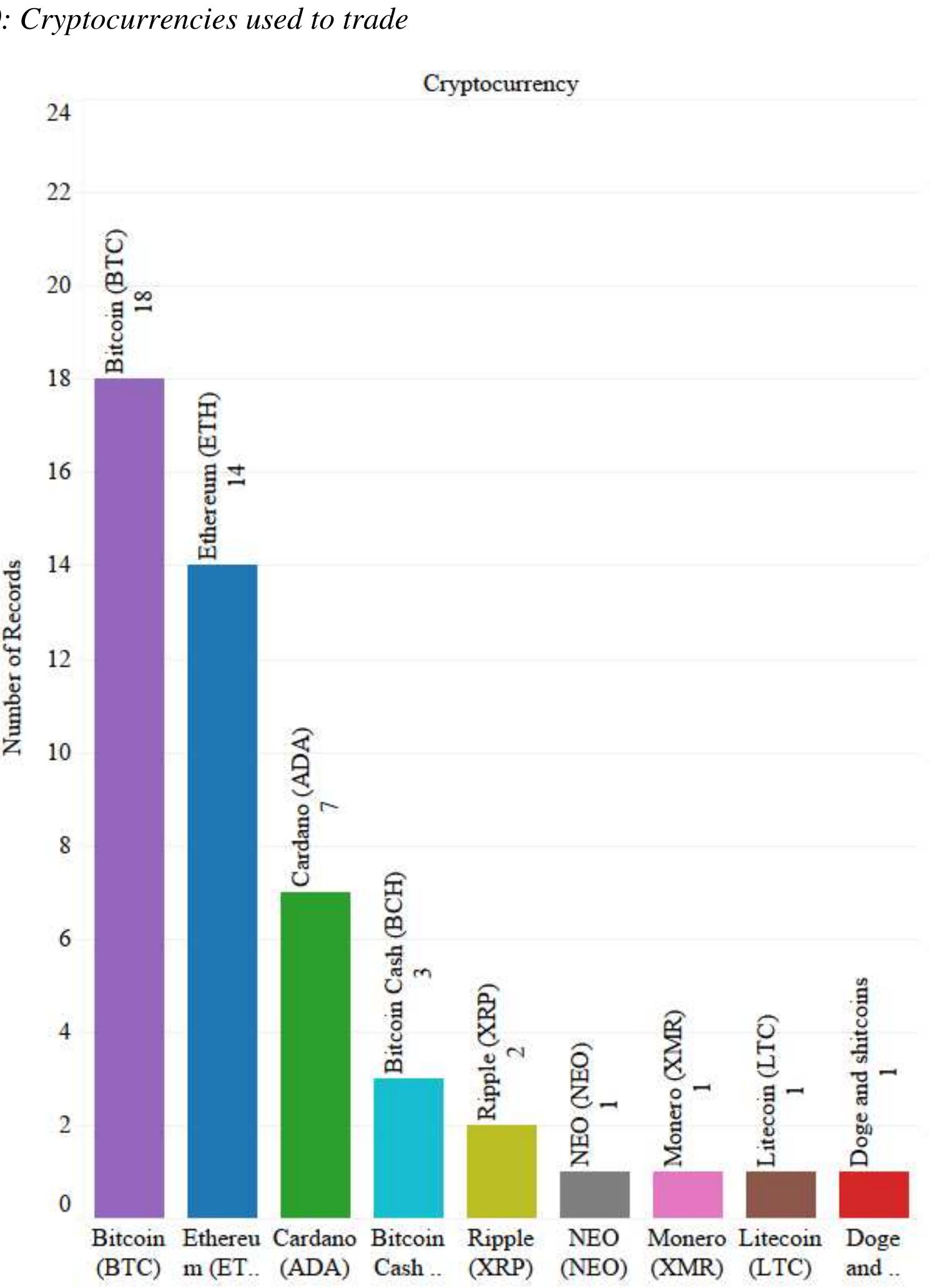

Figure 10: Cryptocurrencies used to trade ............................................................................... 39

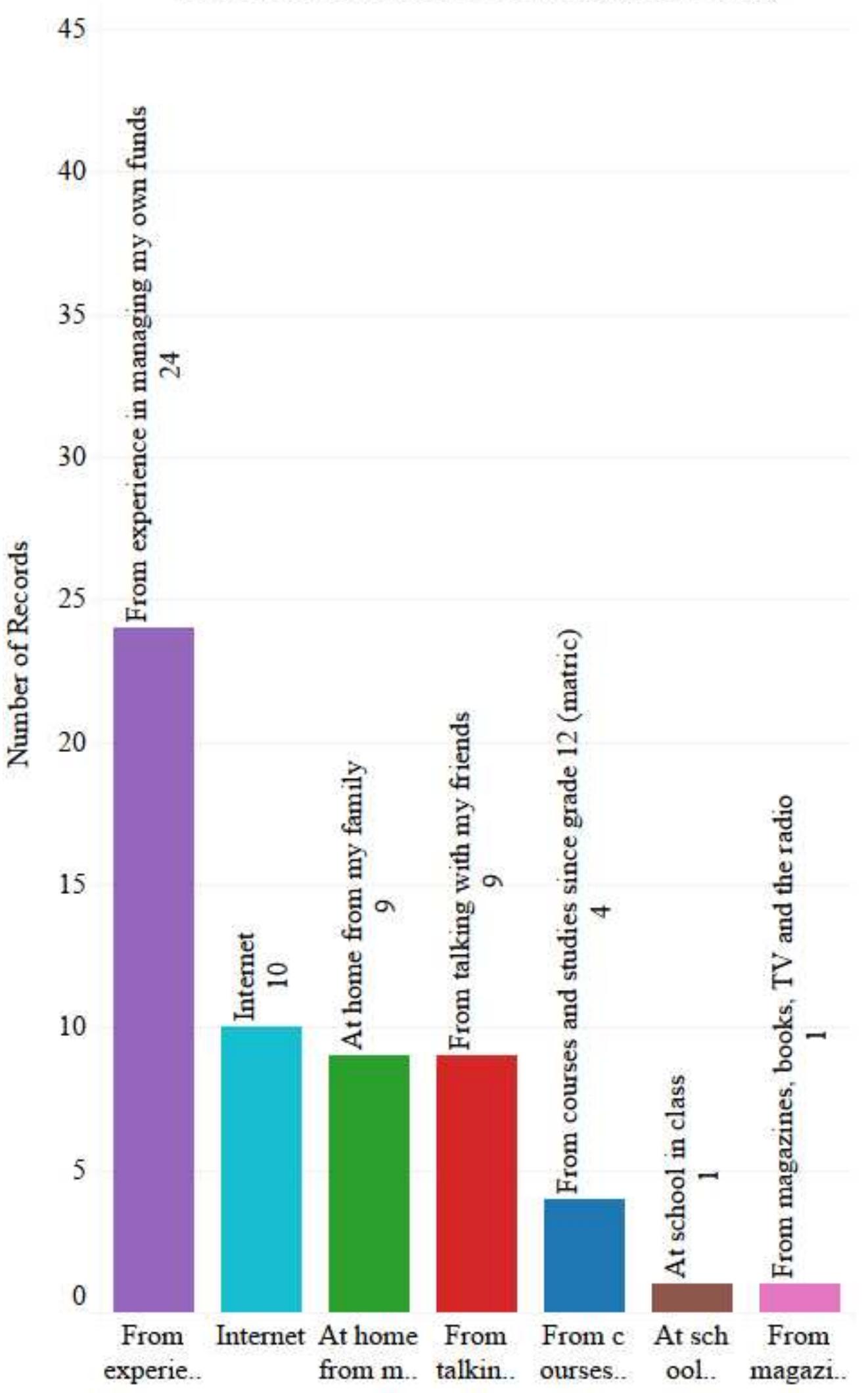

Figure 11: Places where participants learned where to manage their money .......................... 40

Figure 12: Credit card ownership ............................................................................................. 43

Figure 13: Use of a debit card .................................................................................................. 44

Figure 14: Owning a car ........................................................................................................... 45

Figure 15: Behaviour relating to spending habit ...................................................................... 46

Figure 16: Spending habits compared to those who raised the participant .............................. 48

Page 7 of 74

�CHAPTER ONE: RESEARCH OVERVIEW

1.1 INTRODUCTION

The terms financial literacy, financial knowledge, financial education, and financial proficiency

are utilised reciprocally, both in scholastic writing and in the mainstream media (Stolper and

Walter, 2017; Huston, 2010). By the most essential definition, financial literacy alludes to the

learning as well as comprehension of the significance of money and the utilisation of money. It

responds to the inquiry; why spend on this rather than that (Norman, 2010). One's capacity to

comprehend finances addresses the arrangement of abilities and learning that empowers an

individual to choose educated and viable choices all through their execution of their funds

(Rasoaisi and Kalebe, 2015).

Rasoaisi and Kalebe (2015) mention that financial literacy is one of the mainstays of the

monetary prosperity of society, both at a small scale and full-scale level. A monetarily ignorant

society can represent a few issues in the economy. In this way, an absence of financial literacy

has been referred to by various investigations as a noteworthy explanation behind; exorbitant

obtaining and high obligation; low support in the formal budgetary market and securities

exchange; and poor and deficient making arrangements for retirement (Lusardi and Tufano,

2015; Rasoaisi and Kalebe, 2015; Cole, Thomas and Bila, 2008). Basically, this shows how

dangerous money related ignorance is for the prosperity of people, family units and the whole

economy.

There exist a few advantages joined to a monetarily proficient country. Typically, the

microeconomic advantages to people stretch out to delivering macroeconomic advantages for

the economy and the budgetary framework. From a family perspective, money related

capabilities and/or proficiency empowers individuals to augment and better manage their

income and in this manner better oversee life occasions like training, sickness, work misfortune,

or retirement (Rasoaisi and Kalebe, 2015).

Likewise, a financially literate network can all the more likely survey the money related

approaches of their individual governments and activities of the budgetary framework (Pearson,

Stoop and Kelly-Louw, 2017). Moreover, the money related division of an economy with

financially knowledgeable citizens can be successful and develop at a quickened rate, thus, add

to the accomplishment of financial development (Pearson, Stoop and Kelly-Louw, 2017).

Page 8 of 74

�Financial literacy is therefore important for citizens, especially people who are earning,

borrowing and spending, in other words, participating in economic activities.

According to Claeys, Demertzis and Efstathiou (2018), “money is a social establishment that

fills in as a unit of record, a mode of trade and a store of significant worth”. With the

development of decentralised ledger technology (DLT), digital currencies speak to another type

of money. This type of money is privately issued, advanced and it empowers distributed

exchanges. In essence, it enables peer-to-peer transactions (Claeys, Demertzis and Efstathiou,

2018).

Cryptocurrencies are a global phenomenon that could possibly replace fiat currencies

(governmentally regulated money) in the near future. Since the world is progressing towards a

cashless society, cryptocurrencies continue to gain momentum (Goyal, 2018).

The way that a few people, these days, execute through electronic money keeps on asserting

proposals that digital forms of money could be the monetary standards of things to come (Goyal,

2018). Be that as it may, it will take some time before they discover their way into the

mainstream flow of usage, given the solid resistance from controllers or regulators around the

globe (Goyal, 2018). While there are numerous focal points of digital forms of money over fiat

money, it appears that cryptographic forms of money are not yet developed enough to supplant

the present standard installment technique (Goyal, 2018).

Financial institutions and governments are getting wise to the proliferation of cryptocurrencies,

with some, like Sweden and Russia, already well on their way to developing their own national

altcoins. They seek to take advantage of the efficient enforcement of interest, ease of taxation

and cost savings that digital currency offers, without the security issues, money laundering

facilities and lack of central oversight (Claeys, Demertzis and Efstathiou, 2018).

Evaluating the degree of financial literacy of cryptocurrency users is vital. Users are classified

as individuals who trade cryptocurrency and/or who own or hold cryptocurrency for personal

or business use. Users need to understand and know the foundations of everyday constructs of

financial literacy to help them stay secure in equally the short-term and long-term, protect their

financial health and make critical decisions.

A study undertaken by a financial services company showed individuals with low personal

financial literacy acquire more by means of spending, have less riches and pay a lot more

redundant expenses for budgetary items (Zucchi, 2019). As it were, those with lower financial

Page 9 of 74

�literacy will, in general, increase their purchases on their credit card and end up not being able

to pay their full remaining balance every month. In turn, this means that their interest will

accumulate and they will pay more than they can afford. Although crypto is not a credit system

in itself, one may go through the channels of fiat money to borrow money to acquire crypto

thus spend on interest.

A study conducted by Fachrudin (2016), within the context of ‘stock right investment

decisions,’ states that financial literacy is found to fortify the connections among training and

experience toward venture choices. The suggestion is that budgetary proficiency is imperative

for the correct venture choice. More recently, Bellofatto, D’Hondt and De Winne’s (2018) study

on financial literacy in the context of retail investors’ behavior conclude that people who have

higher levels of financial literacy report that their investments are ‘smarter’. Could this hold

true in the cryptocurrency user context?

A study undertaken by Fridayani and Sadewo (2018) concluded in their investigation on traders,

that:

merchants do not have composed and deliberate financial reports that reflect everyday

income and expenses,

traders do not strive to save,

traders have a negative tendency of spending money and,

venture for future needs are not a need.

Might this be the case in the context of cryptocurrency traders? As cryptocurrency has become

a popular medium of exchange, there is much that needs to be researched about the current level

of personal financial literacy of cryptocurrency users.

1.2 GOALS OF THE RESEARCH

The principle point of the present study is to examine cryptocurrency user’s personal financial

literacy. The following are sub-goals to work towards achieving the main aim of the study:

1.2.1 Assess cryptocurrency users financial knowledge and understanding

1.2.2 Assess cryptocurrency users behaviour relating to financial issues

1.2.3 Assess cryptocurrency users attitude towards financial matters

Page 10 of 74

�1.3 METHODS, PROCEDURES, TECHNIQUES AND ETHICAL CONSIDERATION

This study adopted a positivist paradigm to objectively explore the level of financial literacy

amongst cryptocurrency users utilising strategies and methodologies that can be reproduced.

To give legitimate determinations and recommendations, a descriptive research design was

adopted for this study. The present study gathered information to give a reasonable depiction

of the level of cryptocurrency users’ personal financial literacy.

Based on the research design, a survey research strategy was adopted. The data was gathered

by means of a standardised questionnaire, which has been adapted from van Nieuwenhuyzen’s

(2009) ‘Survey of Personal Financial Literacy’. The all-inclusive questionnaire is designed to

include core personal finance characteristics. The questionnaire sections are divided into

financial literacy on financial knowledge and understanding, behaviour relating to financial

issues, and participants' attitude towards financial matters.

A convenience sampling procedure was pursued and this is under the umbrella of a non-

probability sampling method. Convenience sampling involves gathering data from individuals

from the populace who are most effectively open, advantageously accessible and who can give

the ideal and significant data (Sekaran, 2001).

For the scope of the study, a sample size of 32 participants was taken for statistically sound

analysis. The researcher approached crypto-user communities through cryptocurrency forums

and social media.

The data was analysed by means of descriptive statistics to access the level of financial literacy

among cryptocurrency users in terms of the financial literacy constructs. In order to test the

instruments unwavering quality (reliability) and internal consistency of the data collected,

Cronbach’s Alpha was calculated.

This research was as per the moral necessities set out by the Rhodes University Human Ethics

Committee protocol. All ethical considerations regarding informed consent, voluntary

participation, non-disclosure, confidentiality, utilisation and storage of the data collected were

adhered to throughout the study.

Page 11 of 74

�CHAPTER TWO: FINANCIAL LITERACY

2.1 INTRODUCTION

Financial literacy is a fundamental concept used to understand money and in getting money for

the utilisation in day by day life (Sarigül, 2014). This incorporates the manner in which income

and expenditure are managed and the capacity to utilise the regular techniques for trading and

overseeing money (Sarigül, 2014). Further, “financial literacy incorporates an understanding of

everyday situations that need to be understood such as insurance, credit, savings and

borrowings” (Sarigül, 2014). In addition, financial literacy is about the expertise to use

information and comprehension to settle on advantageous budgetary choices. Moreover, the

conduct and frame of mind of individuals can either stimulate or decrease their personal

financial literacy.

Considering the above, the following chapter will provide a detailed theoretical discussion on

financial literacy. It will provide the definition, importance, the current state and measurements

of financial literacy. Additionally, a section on previous financial literacy studies will be

highlighted.

2.2 DEFINITION OF FINANCIAL LITERACY

Sarigül (2014) confirms that monetary proficiency originated from the Jump$tart Coalition for

Individual Money related Education in its 1997 debut investigation of financial literacy among

students in High School. In this examination, the coalition characterises financial literacy as

"the ability to use knowledge and skills to manage one's financial resources effectively for

lifetime financial security" (Sarigül, 2014, p.209; Hastings, Madrian and Skimmyhorn, 2012,

p.5). Be that as it may, as it occurs in many research regions, various specialists and associations

have characterised financial literacy from numerous points of view.

“Personal finance describes the principles and methods that individuals use to acquire and

manage income and assets. Financial literacy is the ability to use knowledge and skills to

manage one’s financial resources effectively for lifetime financial security (Sarigül, 2014).

Financial literacy is not an absolute state; it is a continuum of abilities that is subject to variables

such as age, family, culture, and residence. Financial literacy refers to an evolving state of

competency that enables each individual to respond effectively to ever-changing personal and

economic circumstances” (Mandell, 2008). According to Vitt, Anderson, Kent, Lyter,

Siegenthaler and Ward (2000), financial literacy is the capacity to peruse, examine, oversee,

Page 12 of 74

�and communicate about the personal financial conditions that influence material prosperity. It

incorporates the capacity to observe monetary decisions, examine cash and budgetary issues

without (or in spite of) inconvenience, plan for the future and react competently to life occasions

that influence regular money-related choices, incorporating occasions in the general economy.

Sarigül (2014) states that the financially proficient people are: “1) knowledgeable, educated,

and informed on the issues of managing money and assets, banking, investments, credit,

insurance, and taxes; 2) understand the basic concepts underlying the management of money

and assets; 3) use that knowledge and understanding to plan and implement financial decisions.”

2.3 IMPORTANCE OF FINANCIAL LITERACY

From generations before, money was utilised for most every day buys; today, it is every so

often given out physically. The manner in which individuals shop has changed also (Dechtman,

2018). Web-based shopping has turned into the top decision for some, making adequate chances

to utilise and overextend credit – a very simple approach to over accumulate unnecessary debt,

very fast (Dechtman, 2018).

In the meantime, credit card organisations, banks, and other financial establishments are

immersing customers with credit opportunities (Dechtman, 2018). For instance, the capacity to

apply for Mastercards or pay off one card with another is becoming a norm. Unfortunately, this

is all done without the best possible learning or balanced governance, it is anything but difficult

to fall into money related difficulty (Dechtman, 2018).

Numerous buyers have had almost no comprehension of funds, how credit works and the

potential effect on their money related prosperity for numerous years. Indeed, the absence of

monetary comprehension (financial literacy) has been motioned as one of the fundamental

explanations for reserve funds (savings) and investing issues faced by many individuals.

An absence of financial literacy is not an issue just in rising or developing economies.

Individuals in first-world economies also tend to neglect to show a solid handle of money

related standards so as to comprehend and arrange the monetary scene, oversee budgetary

dangers successfully and keep away from budgetary entanglements. Countries all-inclusive,

from Korea to Australia to Germany, are consumed with populaces who do not grasp financial

related basics.

The degree of financial literacy changes according to the educational levels and financial

situations of the individuals under study. Although, research suggests that highly educated

Page 13 of 74

�individuals with high incomes can be just as ignorant about financial issues as less-educated,

lower-income consumers (however as a rule, the later will, in general, be less monetarily

educated) (Dechtman, 2018).

Being financially literate empowers people to profit from the choices that lead legitimately to

a financially secure future, one that ensures that all assets are protected.

Classifications that regularly become possibly the most important factor with financial literacy

are ordinary budgetary issues like planning, spending, obligations such as debt, and charges

like taxes, retirement reserve funds, school investment funds, and mortgage management.

Burrowing further, financial literacy can likewise incorporate increasingly obscure subjects,

such as contributing to investments, seeing how loan fees work, latent versus dynamic salary,

and financial planning.

According to Zucchi (2019), people can participate in money related proficiency in different

ways, as pursues:

Regardless of whether it is googling individual money related articles and auditing

them, airing out a venture book, looking into budgetary issues is one of the most

straightforward and quickest approaches to increase one's awareness (Zucchi, 2019).

An individual may profit by taking an online or in-person money related education

course in any of various subjects, such as bookkeeping, retirement arranging, or putting

something aside for school (Zucchi, 2019).

Listening to fund or potentially venture digital broadcasts (Zucchi, 2019).

Video is an incredible method to assimilate some close to home money exercises,

particularly on putting and taking an interest in the financial exchange (Zucchi, 2019).

A reliable approach to finding out about financial matters is to converse with, and work

with, a money related specialist such as a financial planner. Getting the realities from a

money related master face-to-face is an extraordinary learning practice. Also,

individuals get a significant chance to pose individual monetary inquiries that are

essential to them (Zucchi, 2019).

No individual wants to concede that they are not up to speed on money related proficiency

(financial literacy), and that is justifiable. Be that as it may, it is better to know where one falls

short with their financial knowledge so as to gain more experience in the area and work to

dispose of any weaknesses (Zucchi, 2019).

Page 14 of 74

�To complete that activity right, O’Connell (2019) states that individuals must center on these

potential financial literacy problem areas:

Having the order to construct and continue a firm family unit spending plan is maybe

the most basic stage an individual can take to support their financial needs. Not having

one, or having one and not adhering to it, is an indication that an individual needs to get

taught about cash and investment funds, in the near future (O’Connell, 2019).

If an individual is paying off debtors, a particularly extremely profound obligation that

undermines their money related future, which is an unmistakable warning that they are

needing a more grounded set of individual monetary rules. Individual obligations such

as personal debt are the main barricade to money related security (O’Connell, 2019).

Having 3-6 months of cash stored in a stormy day reserve is a major ordeal. A money

related pad can support unexpected circumstances. Not having a reserve leaves an

individual defenseless against such circumstances, for example, unemployment or

retrenchment (O’Connell, 2019).

On the off chance that an individual cannot comprehend the significance of self-

multiplying dividends (compound interest) and an individual is routinely borrowing,

that is a financial literacy issue - one that is depleting cash that generally would increase

in value after some time (O’Connell, 2019).

Having a decent protection approach on a home, wellbeing, and even asset ventures is

an unquestionable investment. Insurance policies combat against financial disaster. Not

having protection leaves those benefits powerless against misfortune, and is a

reasonable sign that an individual is not up to speed on money-related issues that can

mean the most, when they need it the most (O’Connell, 2019).

2.4 FINANCIAL LITERACY STUDIES

There are numerous examinations that research financial knowledge and financial literacy.

Among them; Danes and Hira (1987) reviewed undergraduate students utilising a survey of 51

questions to gauge their insight into credit cards, protection, individual credits, record keeping,

and generally speaking money related administration. The discoveries demonstrate that males’

financial knowledge is more than females in many regions, wedded understudies know more

than unmarried understudies, and privileged people know more than lower-class people. Their

general finding is that undergraduate students have low money related proficiency (Danes and

Hira, 1987).

Page 15 of 74

�Volpe, Chen and Pavlicko (1996) studied undergraduate business understudies utilising an

instrument of 23 questions that concentrated essentially on investment knowledge. Discoveries

demonstrate a low financial literacy average of 44%, with the individuals who studied business

being more learned on investments than the individuals who did not study business.

Chen and Volpe (1998) directed a monetary proficiency study including 924 undergraduate

students in the USA. The review inspected financial literacy over four primary territories

examined the connection among education and the understudy qualities and broke down the

effect of education on understudy feelings and choices. Chen and Volpe (1998) found that those

understudies with a nonbusiness major and who are female, in lower-class rank, younger than

30 and with little work experience have lower levels of financial knowledge. The examination

shows that these understudies with less information are bound to hold wrong suppositions and

settle on inaccurate choices (Chen and Volpe, 1998).

Hogarth (2002) investigated the financial proficiency of grown-ups in the USA utilising 28

binary types (true/false) inquiries on personal finance subjects. The examination demonstrates

that, all in all, less monetarily educated respondents are bound to be single, moderately

uneducated, generally low salary, minority, and either youthful or old (not moderately aged).

Volpe, Kotel and Chen (2002) overviewed financial specialists, specifically investors, to

inspect their investment proficiency and the connection among education and online speculator

qualities. The consequences of their examination show that investors who are 50 years old or

more seasoned are more proficient than the individuals who were more youthful. Ladies have

lower levels of investment knowledge than men. Financial specialists with advanced education

are more learned than those with secondary school or college qualifications. The individuals

who exchange/trade online are increasingly more knowledgeable (Volpe, Kotel and Chen,

2002).

Worthington (2006) investigated the financial literacy of Australian adults. The investigative

system utilised in the examination was to determine every respondent's money related education

quintile as the reliant variable with socioeconomic, demographic and financial and monetary

qualities as indicators. Aftereffects of the investigation recommended that money related

proficiency was seen as most noteworthy for people matured somewhere in the range of 50 and

60 years, experts, business and homestead proprietors. Financial literacy was most minimal for

jobless, females and those from non-English talking foundations with a low degree of

instruction (Worthington, 2006).

Page 16 of 74

�Lusardi, Mitchell and Curto (2010) inspected financial proficiency among youthful grown-ups.

They demonstrated that budgetary education is low; 33% of young adults have less than

adequate fundamental knowledge of loan fees such as interest rates, risk diversification, and

inflation. Money related proficiency is, unequivocally, identified with sociodemographic

qualities and family monetary refinement.

Van Rooij, Lusardi and Alessie (2011) conceived two extraordinary modules to gauge financial

literacy and concentrate its relationship to securities exchange interest. They found that most of

the respondents show fundamental budgetary information or financial knowledge and have

some inclinations about compound interest, time value of money and inflation (Sarigül, 2014).

Their appraisals demonstrated that the connection among education and financial exchange

interest stays positive and statistically significant. The researchers found that financial

proficiency influences basic financial decision-making. Individuals with lowered financial

knowledge and attitude are considerably less prone to put resources into stocks (Sarigül, 2014;

Van Rooij, Lusardi and Alessie, 2011).

2.5 SUMMARY

In summary, financial literacy is significant in light of the fact that it arms people with the

learning and aptitudes they have to oversee financial decisions successfully. Without it,

monetary choices and the moves made, or are not made, do not have an educated establishment

to augment their prosperity. What is more crucial is that low levels of financial literacy can

have critical outcomes.

Page 17 of 74

�CHAPTER THREE: CRYPTOCURRENCY

3.1 INTRODUCTION

Monetary forms like the U.S. dollar or the South African Rand are managed and confirmed by

a focal power or central authority, normally a bank or government. Under the focal position

framework, a client's information and money are in fact defenseless before their bank or

government (McWhinney, 2019). In the event that a client's bank breakdown or they live in a

nation with a temperamental government, the estimation of their money might be in danger

(McWhinney, 2019). These are the stresses to which blockchain was originated from.

Envision having practically quick access to a lasting record of every advanced digital

transaction over the world. Without uncovering exactly who and what is associated with these

exchanges, this advanced database awards an individual almost real-time views of distributed

trade inside and over national borders (Nakamoto, 2008). Such extraordinary ability to screen

direct Web-based connection between quasi-anonymous people who embrace, confirm, and

distribute records of their advanced exchanges is at the center of guarantees and fears

encompassing blockchains (McWhinney, 2019; Nakamoto, 2008).

Blockchain and cryptographic forms of money will drastically change how people do

exchanges, similarly as the internet revolutionised how we communicate. Digital forms of

money open up numerous chances, for example, quick, effective, recognisable, and secure

exchanges, yet additionally have downsides, for example, their intrinsic risk, the financial and

innovative difficulty as well as the budgetary trouble of utilising them, and the questionable

social view of owning them (Arias-Oliva, Pelegrin-Bolrondo and Matias-Clavero, 2019). The

intricacy and results of the blockchain and digital money transformation make it basic to break

down its effects and difficulties to analyse and gain knowledge within the context (Arias-Oliva,

Pelegrin-Bolrondo and Matias-Clavero, 2019).

Considering the abovementioned, the following chapter will give a comprehensive theoretical

discussion around what blockchain and cryptographic money is, the rise of digital money, the

job of cryptographic money in the monetary markets, the dangers in question and the

significance of budgetary education among digital currency clients

Page 18 of 74

�3.2 BLOCKCHAIN

At their substance, blockchains are computerised groupings of numbers coded into computer

programming that grant the protected trade, recording, and broadcasting of exchanges between

individual clients working anyplace in the world with access to the internet (Nakamoto, 2008).

Similar to most technological modifications, the advancement of blockchains drew on and

consolidated a few existing innovations. Blockchains consolidate computerised encryption

advancements that veil, to changing degrees, the particular substance traded just as the

personalities of individual clients (Nakamoto, 2008). Calculations (to which are known as the

algorithms), the pre-coded arrangement of bit by bit directions, are additionally activated in

comprehending complex numerical conditions and landing at a consensus on the legitimacy of

exchanges inside the user network (Nakamoto, 2008). Technology such as time-stamping

advances at that point by intermittently grouping verified transactions into datasets, or 'blocks'

(Nakamoto, 2008).

Connected together successively, these 'blocks' visually structure 'chains' that make up bigger

'blockchain' databases of exchanges or transactions that communicate a permanent record of

transactions while keeping up the secrecy of users and explicit substance traded (Nakamoto,

2008). Blockchains are planned to be sustained by all users in habits intended to be unchanging

except if clients land at an unmistakable consensus to attempt changes (Nakamoto, 2008).

In layman's terms, the blockchain is a decentralised ledger of all exchanges over a distributed

system. This system is known as the peer-to-peer network. Utilising this innovation, users can

affirm transactions without a requirement for a focal clearing authority or an outsider, for

example, a bank. Potential applications can incorporate settling exchanges, casting a ballot,

fund transfers and numerous different issues (Fortney, 2019).

3.3 CRYPTOCURRENCY

Compared to the blockchain, digital money (also known as cryptocurrency) has to do with the

utilisation of tokens dependent on the distributed ledger technology (Fortney, 2019). Digital

currency can be viewed as a device or asset on a blockchain network, generally, blockchain is

the platform that brings cryptographic forms of money into recreational use (Fortney, 2019).

Recreational use can go from anything like managing purchasing, selling, contributing,

exchanging, or potentially other fiscal viewpoints that manage a blockchain local token or sub-

token, for example, digitising the estimation of an asset (Fortney, 2019; Nakamoto, 2008).

Page 19 of 74

�Cryptocurrencies are tokens dependent on the conveyed record that is a blockchain.

Cryptocurrency is a computerised cash frame based on cryptography, or by definition, the craft

of unraveling or composing codes (Priyadarshini, 2019). Albeit all are viewed as digital

currencies, these tokens can fill various needs on these systems (Priyadarshini, 2019).

By spreading its activities over a system of computers, blockchain permits Bitcoin and different

digital forms of money to work without the requirement for a focal power (Fortney, 2019;

Nakamoto, 2008). This decreases risk as well as takes out a considerable amount of the

processing and exchange expenses such as transaction fees. It likewise gives those in nations

with volatile monetary standards a progressively steady currency with more applications and a

more extensive system of people and organisations they can work with, both locally and

universally (Fortney, 2019).

3.4 EVOLUTION/EMERGENCE OF CRYPTOCURRENCY

Cryptocurrency developed out of need (Wall Street, 2018). About ten years after the launch of

bitcoin, the first and most conspicuous cryptographic money, advanced monetary forms keep

on developing (Wall Street, 2018). In spite of being around for not exactly 10 years,

cryptocurrencies as of now demonstrate the possibility to supplant customary fiat monetary

forms and change the budgetary administration's landscape (Wall Street, 2018; Redman, 2017).

Fiat currency is money that an administrative authority (such as a government) has pronounced

to be legitimate legal tender, while digital money is certifiably not a lawful tender and not

supported by a legislature. Cryptographic money suggests, "a decentralised and digital medium

of exchange governed by cryptography” (Redman, 2017). Both are monetary forms, yet there

are some eminent contrasts.

As expressed above, fiat currency is governmentally backed. The currency can appear as money

imprinted on paper, for example, physical dollars, or it tends to be spoken to electronically, for

example, with bank credit to which is accessed by a VISA card or MasterCard (Surbhi, 2019).

While paper cash was customarily esteemed by a physically rare/scare commodity, for example,

gold or silver, these days, fiat money is bolstered by a faith-based framework that relies upon

market interest to which the administration controls the stockpile and individuals can settle their

regulatory expenses (for instance, taxes) with it (Surbhi, 2019).

Page 20 of 74

�Cryptocurrency is not backed by a central government or bank (it is decentralised as well as

global) (Surbhi, 2019). It very well may be seen as a bank credit minus the bank (Surbhi, 2019).

A calculation controls the inventory and individuals cannot adhere to their regulatory

obligations with it in light of it not being government-backed. Although, you can pay taxes on

it (Surbhi, 2019).

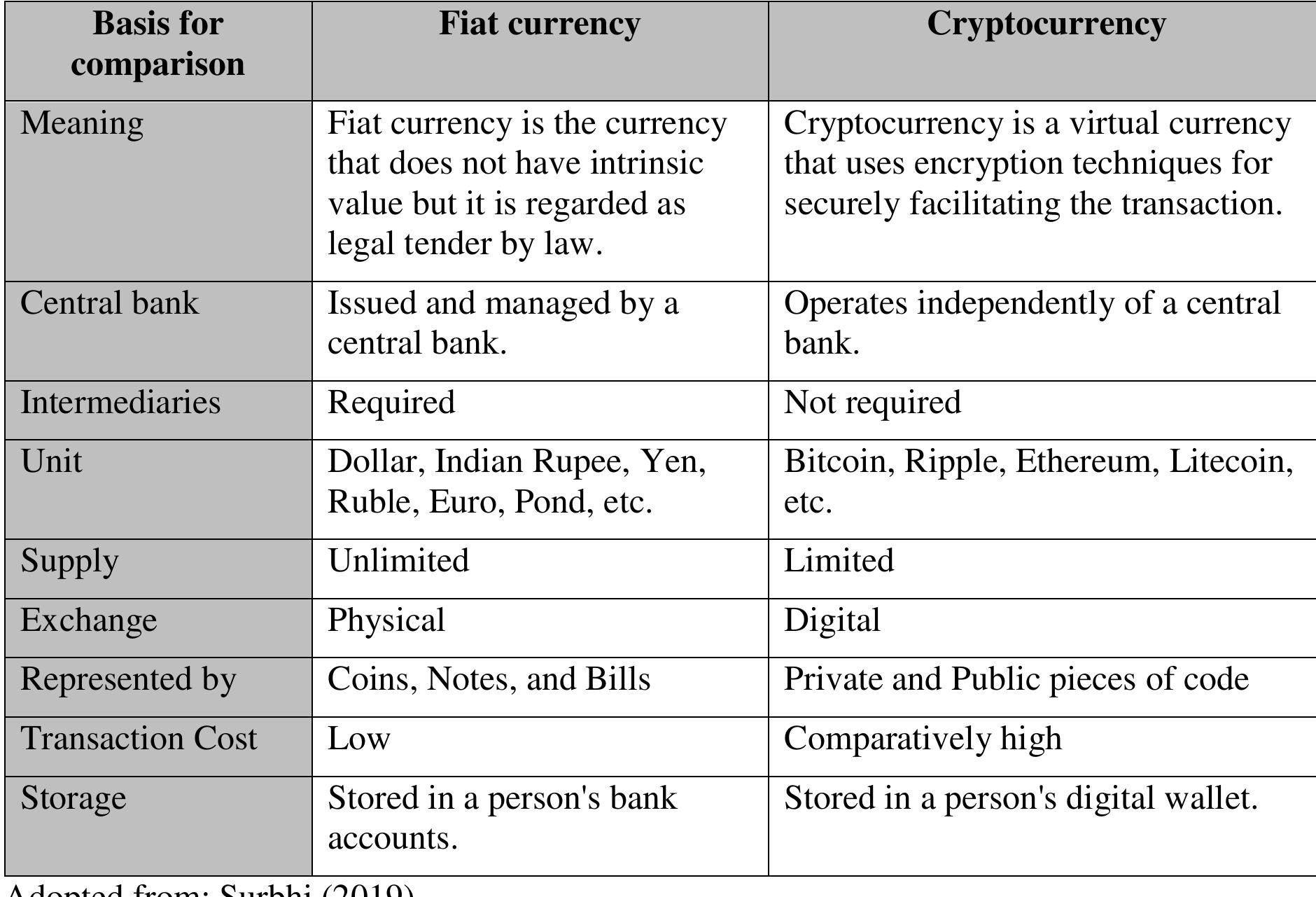

The below table compares fiat currency to cryptocurrency

Table 1: Fiat Currency vs Cryptocurrency

Basis for Fiat currency Cryptocurrency

comparison

Meaning Fiat currency is the currency Cryptocurrency is a virtual currency

that does not have intrinsic that uses encryption techniques for

value but it is regarded as securely facilitating the transaction.

legal tender by law.

Central bank Issued and managed by a Operates independently of a central

central bank. bank.

Intermediaries Required Not required

Unit Dollar, Indian Rupee, Yen, Bitcoin, Ripple, Ethereum, Litecoin,

Ruble, Euro, Pond, etc. etc.

Supply Unlimited Limited

Exchange Physical Digital

Represented by Coins, Notes, and Bills Private and Public pieces of code

Transaction Cost Low Comparatively high

Storage Stored in a person's bank Stored in a person's digital wallet.

accounts.

Adopted from: Surbhi (2019).

An advantage of cryptocurrency is that it is exceptionally resistant to the probability of the

extreme expansion that has been known to torment fiat cash (Redman, 2017). Because of a 21-

million-algorithmically customised spending cap set on Bitcoin, there is a restricted inventory

of the amount of this currency that can be created, making inflation incomprehensible (Barone,

2019; Nakamoto, 2008). This stands out from Fiat currency, which can be unimaginably printed

at the client's cost, prompting expanded rates and an overdose of creation of paper charges that

have little worth (Barone, 2019).

An inadequacy of cryptocurrency, contingent upon how one’s perspectives are, is that there is

massive client opportunity because of absence of an outsider power supporting all exchanges

Page 21 of 74

�(International IF, 2018). This implies that cryptocurrencies may likewise, similar to fiat

currency, be utilised to take part in criminal behavior, for example, purchasing non-prescribed

medications or erotic entertainment (International IF, 2018). Besides, because of the absence

of regulation, crypto users are additionally ready to abstain from making good on regulatory

expenses. As a result of this consent-less framework, governments are currently attempting to

get progressively included and control Bitcoin to maintain a strategic distance from false and

criminal behavior (International IF, 2018).

Since the utilisation of fiat currency requires commitment with government establishments, for

example, identity documents when opening a bank account, it is a lot simpler to track issues

manifesting in criminality (International IF, 2018). It is not necessarily the case that

rebelliousness just happens in the realm of cryptocurrency. For a considerable length of time,

organisations and banks have been introducing more grounded guidelines and regulations to

manage the black market of fiat currency exchange that prompts crime and extortion

(International IF, 2018). Disregarding the way that it is progressively harder to follow the source

of the fake conduct of cryptographic money as a result of the namelessness connected to the

computerised wallets on the blockchain, it cannot be said that fiat money is essentially more

secure than a cryptocurrency (International IF, 2018).

3.5 ROLE OF CRYPTOCURRENCY IN FINANCIAL MARKETS

Cryptocurrency speaks to the start of another period of innovation-driven markets that can

possibly disturb regular market techniques, longstanding strategic approaches and set up

administrative points of view (Marr, 2017). Yet, all to the advantage of buyers and more

extensive macroeconomic proficiency (Marr, 2017). Digital currencies convey the earth-

shattering potential to permit customers, anyplace or whenever, access to a worldwide monetary

system in which investment is confined distinctly by access to innovation, instead of by

components, for example, having a record of loan repayment or a ledger (Marr, 2017;

Tabbebaum, Kashyap and Lowy, 2015).

Tabbebaum, Kashyap and Lowy (2015) expressed that, for buyers, cryptographic forms of

money offer less expensive and quicker peer-to-peer payment choices than those offered by

conventional cash administrations organisations, without the need to give individuals personal

details. While digital forms of money keep on increasing some acknowledgment as a payment

alternative, cost instability or price volatility and the opportunity for speculative ventures urge

Page 22 of 74

�customers to not utilise cryptocurrency to buy products and services but instead to trade with it

(Tabbebaum, Kashyap and Lowy, 2015).

Just “6% of respondents to PwC's 2015 Consumer Cryptocurrency Survey state they are either

‘very’ or ‘extremely’ familiar with digital forms of money” (Tabbebaum, Kashyap and Lowy,

2015). Tabbebaum, Kashyap and Lowy (2015) envision that recognition will increment as

buyers begin to gain more access to such innovative approaches and administrations not

generally accessible through conventional payment frameworks.

From the point of view of organisations and traders, cryptocurrencies offer low exchange

expenses such as transaction fees and they take out the probability of chargebacks (the interest

by a third party supplier (for example, Visa) that a retailer follows through on the passing of a

false or questioned exchange) (Tabbebaum, Kashyap and Lowy, 2015).

Numerous capable technology engineers have given their endeavors to cryptocurrency mining,

while others have concentrated on increasingly pioneering interests, for example, developing

exchanges, wallet administrations and alternate cryptographic forms of money (Tabbebaum,

Kashyap and Lowy, 2015). Tabbebaum, Kashyap and Lowy (2015) see the digital currency

market as just beginning to pull in ability with the perceptiveness, broadness and market center

expected to take the business to the following level. For the market to accelerate mainstream

acknowledgment, nonetheless, customers and organisations should consider digital currency to

be an easy to use answer for their normal exchanges. Likewise, the industry should create

cybersecurity innovation and conventions protocols.

Tabbebaum, Kashyap and Lowy (2015) notice that generally, banks have linked those with cash

to the individuals who need it. Be that as it may, as of late, this mediator position has been

weakened, and disintermediation in the financial segment has developed quickly. This has come

about because of the ascent of internet banking; expanded purchaser utilisation of alternate

payment systems like Amazon gift vouchers, Apple Pay and Google Wallet; and advances in

portable installments such as mobile payments (Tabbebaum, Kashyap and Lowy, 2015).

Governmental attitudes toward cryptocurrencies are conflicting with regards to the

characterisation, treatment, and legitimateness of digital money. Guidelines are additionally

developing at various paces in various districts (Tabbebaum, Kashyap and Lowy, 2015).

Digital forms of money are a developing business sector and the eventual fate of cryptographic

money could unfurl from various perspectives (Fisher-French, 2017). It remains to be perceived

Page 23 of 74

�how this market will advance and whether digital forms of money will progress toward

becoming standard or be consigned to specific specialties; how conventional monetary

organisations will adjust to them and incorporate them, or relinquish the space to non-customary

organisations; additionally, it needs to be noted whether governments and controllers will grasp

cryptocurrency, endure cryptocurrency, or delegitimise cryptocurrency (Koshoff, Lee and

Bridgers, 2018). In the event that customary money related establishments join this developing

business sector, they ought to apply sound risk management practices for monetary, innovative,

and developing emerging market risk

3.6 RISKS OF CRYPTOCURRENCY ON GLOBAL FINANCIAL MARKETS

Bitcoin was the earliest form of cryptographic money and remains the most vigorously

exchanged digital currency. Bitcoin began as a baffling path for a little gathering of technically

knowledgeable crypto-adventurers to abstain from utilising customary fiat cash (Koshoff, Lee

and Bridgers, 2018; Marr, 2017). Bitcoin and alternate digital forms of money have developed

into an enormous market worth several billion U.S. dollars. This production of significant worth

has made users take note and have considerable enthusiasm for owning and exchanging

cryptographic forms of money (Koshoff, Lee and Bridgers, 2018). Ongoing patterns show that

numerous traditional financial services firms are investigating the probability of entering the

cryptocurrency markets (Koshoff, Lee and Bridgers, 2018).

Cryptocurrency is an indistinguishable mix of budgetary instruments, supporting innovation,

and an internet empowered system. Along these lines, with regards to cryptographic forms of

money, budgetary dangers can only, with significant effort, be isolated from technological risks

(Koshoff, Lee and Bridgers, 2018). The cryptographic money market requires financial risk

management to keep away from digital currencies that are not a going concern, to appropriately

differentiate portfolios, and to oversee liquidity (Koshoff, Lee and Bridgers, 2018). The digital

currency market requires technology risk management to appropriately ensure private keys are

protected and to support cybersecurity (Koshoff, Lee and Bridgers, 2018).

On the off chance that digital currencies were viewed as a type of foreign currency, at that point,

the conversion standard with respect to the U.S. dollar would be very unpredictable. During the

three-month time frame from December of 2017 to February of 2018, Bitcoin fell by over half

its market value. In addition, Bitcoin.com announced that 46% of the digital currencies that

held opening contributions in 2017 had failed. This implies financial services organisations

should practice reasonable trustee obligation through teaching financial specialists, giving

Page 24 of 74

�decorous disclosures, and cautiously managing portfolio proposals that include cryptographic

forms of money (Koshoff, Lee and Bridgers, 2018).

As indicated by Koshoff, Lee and Bridgers (2018), the digital money market additionally has a

high measure of liquidity risk. As indicated by the crypto-media organisation, CoinDesk (Luu,

2017), “the total cost of making a $1 million bitcoin transaction can run between $10,000 to

$100,000 more than the listed spread on an exchange.” Concentrated digital money trades, for

example, Coinbase or Kraken, have been ill-equipped to deal with the developing interest of

cryptographic money, bringing about bottlenecks and liquidity issues (Koshoff, Lee and

Bridgers, 2018; Luu, 2017).

(Koshoff, Lee and Bridgers (2018) have maintained that investors and financial institutions

cannot separate the empowering innovation and the related mechanical dangers from the

cryptographic money. The fame and pertinence of the hidden blockchain technology supporting

every cryptographic money will unavoidably affect the estimation of the digital currency

(Koshoff, Lee and Bridgers, 2018). On the off chance that the blockchain technology comes to

be obsolete, at that point the related cryptographic money may lose all worth. Therefore, the

danger of obsolete technology is another risk consideration (Koshoff, Lee and Bridgers, 2018).

Besides, the utilisation of blockchain makes exceptional dangers in overseeing guardianship

since evidence of-proprietorship. In the event that a user loses a private key, at that point, the

digital currency cannot be traded or utilised. Losing a private key makes the estimation of the

related digital money be lost (Fortney, 2019). With a blockchain, there is no central authority;

nobody with the super-user or executive secret key; nobody who can overwrite changes that

were made (Fortney, 2019).

Cryptographic forms of money are a developing business sector, and all things considered, not

the majority of the traditional elements of a developed monetary market have been set up

(Spencer, 2017). For instance, it is hard to set up who lawfully claims a measure of digital

currency since private keys can become compromised. Money related establishments may take

care of this issue by making a focal computerised vault for putting away private keys and

following proprietorship through conventional bank records off of the blockchain (Spencer,

2017). Notwithstanding, this arrangement makes extra intricacy around cryptographic forms of

money just as a solitary purpose of disappointment that could prompt enormous misfortunes.

Besides, a focal advanced vault would cause digital forms of money to end up dependent upon

Page 25 of 74

�administrations given by authority banks, in this manner the cryptographic money would lose

the upside of being a decentralised distributed mechanism of trade (Spencer, 2017).

Meyer (2018) argues that there is another risk identified with the development of the

cryptographic money market and this risk lies in the legitimate systems of different jurisdictions

around the world. “Cryptocurrencies are geographically everywhere, which means any large

country can introduce political and regulatory risk into a cryptocurrency network” (Meyer,

2018). Nations that criminalise cryptocurrencies may likewise try to deny access through their

routers, while different nations may have reduced technological infrastructural foundations,

making exchanges troublesome (Meyer, 2018).

3.7 IMPORTANCE OF FINANCIAL LITERACY AMONG CRYPTOCURRENCY USERS

The cryptocurrency market is like the stock market, but, the key differences being, that the

cryptocurrency market is a global market that moves much faster and is active 24/7 (Casey,

2019). But the laws of the market still apply, so what cryptocurrency users are learning while

investing in bitcoin or other cryptocurrencies provides valuable insight into the way other

markets operate (Casey, 2019). Just looking at the recent volatility of the cryptocurrency market

is a lesson in itself for new investors on the highs and lows of investing, for example.

“Cryptocurrency has given people financial freedom they did not know before” (Winco, 2019).

Although this is a good thing, most people are unprepared to take responsibility for their own

money. Most of all people know comes from a centralised mindset, where an authority has held

people’s money and given them orders of when and how they are allowed to reach and use the

money (Winco, 2019).

Today, with the cryptocurrency freedom people are gaining comes the need for financial

education, not that it was not needed previously, after all, financial literacy has always been

crucial, so imagine now with the emergence of cryptocurrency (Winco, 2019).

According to the S&P Global FinLit Survey, the nations with the most noteworthy monetary

proficiency are “Australia, Canada, Denmark, Finland, Germany, Israel, the Netherlands,

Norway, Sweden, and the United Kingdom” (Winco, 2019). The survey also showed that 1 in

3 adults around the world shows some level of understanding of basic financial concepts

(Winco, 2019). Women, the poor, and the less educated are the most affected by the low

financial literacy, such classes are constantly an aim for government programs for “financial

Page 26 of 74

�inclusion”, giving them opportunities that without the right financial literacy can lead to debt,

such as credit cards (Winco, 2019).

It has never been so easy to acquire a credit card, and do not think banks are simply choosing

to be nicer, they are taking advantage of the gap, the lack of financial knowledge (Winco, 2019).

By offering credit cards to the financially illiterate, banks are allowed to charge unreasonable

interest rates and make double off of these people when they do not pay their bills.

The fundamental focus of financial literacy is to help people to cultivate a stronger

understanding of how money works and the basics of financial concepts so that people can

handle their money better. How many crypto users can say they have the right set of skills to

make wise decisions about their finances?

According to Ramsey (2017), in the U.S. a well-developed country has nearly four out of five

workers living paycheck to paycheck. More than a quarter never save money, and almost 75%

are in some form of debt (Ramsey, 2017). If America is displaying these kinds of numbers,

think of the catastrophic numbers for countries under economic crisis and third world countries.

It can be noted that the third world countries are the exact places where cryptocurrencies have

great potential of uplifting the economy, as with Venezuela, Greece, and African nations

(Winco, 2019).

If crypto is the evolution of the monetary system, it can be noted that, from past experiences

with the current monetary system and lack of financial literacy, a nation´s economy cannot be

saved through cryptos, and then watch it destroy itself again for lack of financial education

(Winco, 2019). People must think in the long run and prevent it while it can be prevented. This

revolutionary period is the perfect time to educate the communities at large as well as the

cryptocurrency communities already founded (Winco, 2019).

With a basic understanding and knowledge of financial concepts, people would be equipped to

make smarter financial decisions towards saving, investing, borrowing, and more. People’s

financial behavior and attitudes towards financial matters would be confident in their decisions

by knowing they have made an educated and calculated decision for their future.

3.8 SUMMARY

Cryptocurrencies, such as bitcoin, can possibly displace traditional payment techniques.

Although to accomplish that and become an overwhelming force in the worldwide arrangement

Page 27 of 74

�of monetary systems, they should give particular attention to their gradual increase in value, to

address and conquer various basic difficulties, for example, formal administrative regulatory.

As much as blockchain and cryptocurrency is a fairly new phenomenon, it can be noted that

without a basic understanding of financial literacy, the less control one will have on their

finances. With so much money flowing into the crypto industry and subsequently into the hands

of the young and financially inexperienced generation.

One of the best aspects of getting involved in cryptocurrency is that it forces individuals to take

a closer look at their relationship with their finances and money. The more they understand

about the true nature of money, savings, debt, and risk, the better they can take control of their

own financial future.

Page 28 of 74

�CHAPTER FOUR: METHODOLOGY

4.1 INTRODUCTION

A research methodology is the specific procedures or techniques used to identify, select,

process, and analyse information about a topic. The methodological section of a thesis allows

the reader to critically evaluate a study’s overall validity and reliability. The strategy segment

responds to two primary inquiries: How was the information gathered or produced? How was

it broke down?

This chapter commences with a review of the research design used in the present study. Lastly,

the ethical considerations of the study will be discussed.

4.2 RESEARCH PARADIGM

The present study had a positivist worldview/paradigm since the goal was to examine the level

of financial literacy among cryptocurrency users utilising methods and methodologies that can

be duplicated.

4.3 RESEARCH DESIGN

The research design is a strategy established to attain the research purpose (De Vaus, 2001). It

aims to ensure that the research can clearly answer the research problem, and involves

systematising the research activity, involving the collection of data and analysing the data (De

Vaus, 2001).

To provide valid conclusions and recommendations, a descriptive research design was adopted

for this study. The purpose of descriptive research is to portray an accurate profile of persons,

events or situations (Robson, 2002). This researcher collected data to provide a clearer picture

and accurate profile of the financial literacy level of cryptocurrency users, hence the use of

descriptive research design.

4.4 DATA GATHERING

A survey research strategy was adopted to gather the data based on the research design chosen

for this study. Surveys are commonly made use of as they allow the collection of a large amount

of primary data from a sizeable population in a highly economical way (Saunders, Lewis and

Thornhill, 2007). Often obtained by using a questionnaire administered to a sample, the data is

standardised to allow for easy comparison.

Page 29 of 74

�The data was gathered by means of a standardised questionnaire, which was adapted from van

Nieuwenhuyzen’s (2009) ‘Survey of Personal Financial Literacy’. The comprehensive

questionnaire was designed to cover major aspects of personal finance. It included financial

literacy on general financial knowledge and understanding, behaviour relating to financial

issues, and participants' attitude towards financial matters.

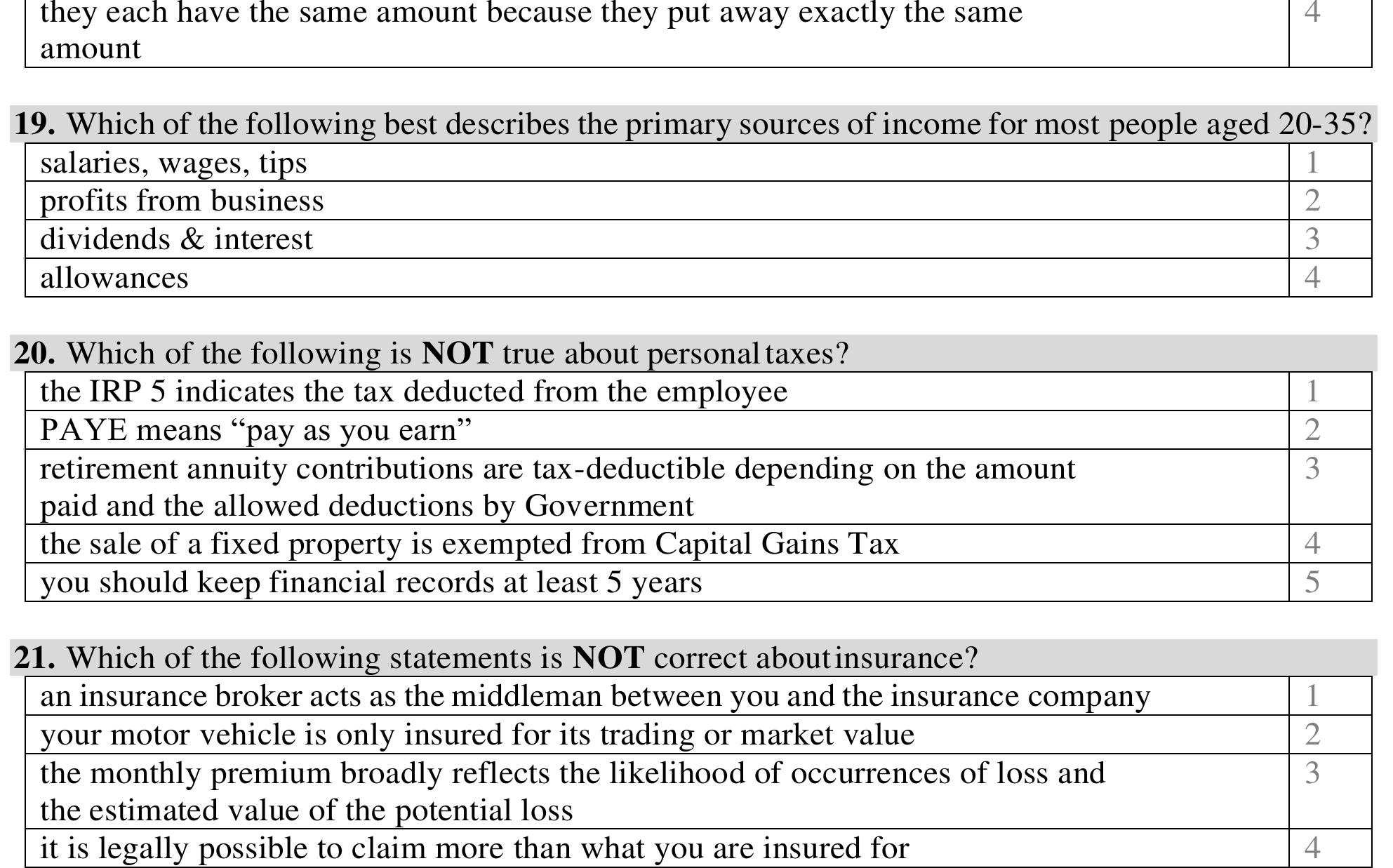

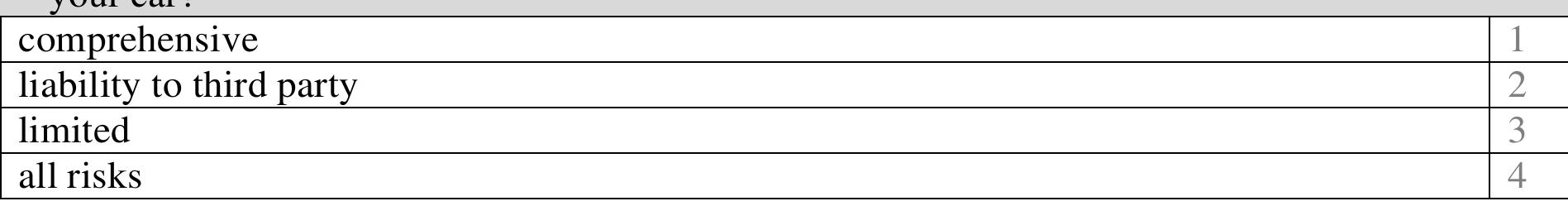

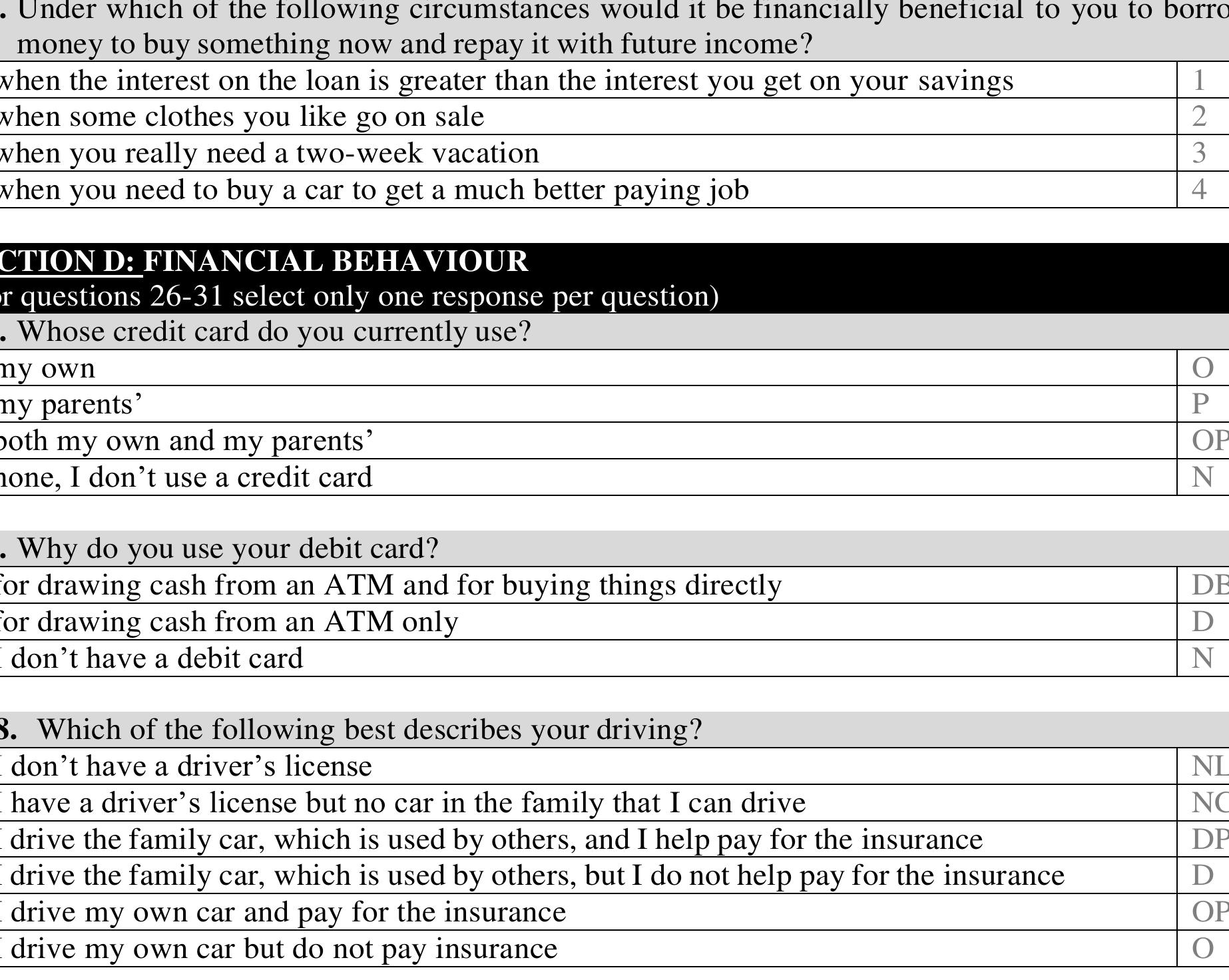

First, participants were required to fill out five demographic and seven data collection

questions. After, participants were requested to answer thirty-six questions which were

comprised of twenty-five questions about their knowledge on personal finance, six questions

of their financial behaviour, and five questions on attitude towards financial matters. The

exploration instrument was intended to contain information that could usefully be measured to

enable the analyst to respond to the examination questions and to meet the targets of the

investigation. The questionnaire utilised within the present study can be found in Appendix A

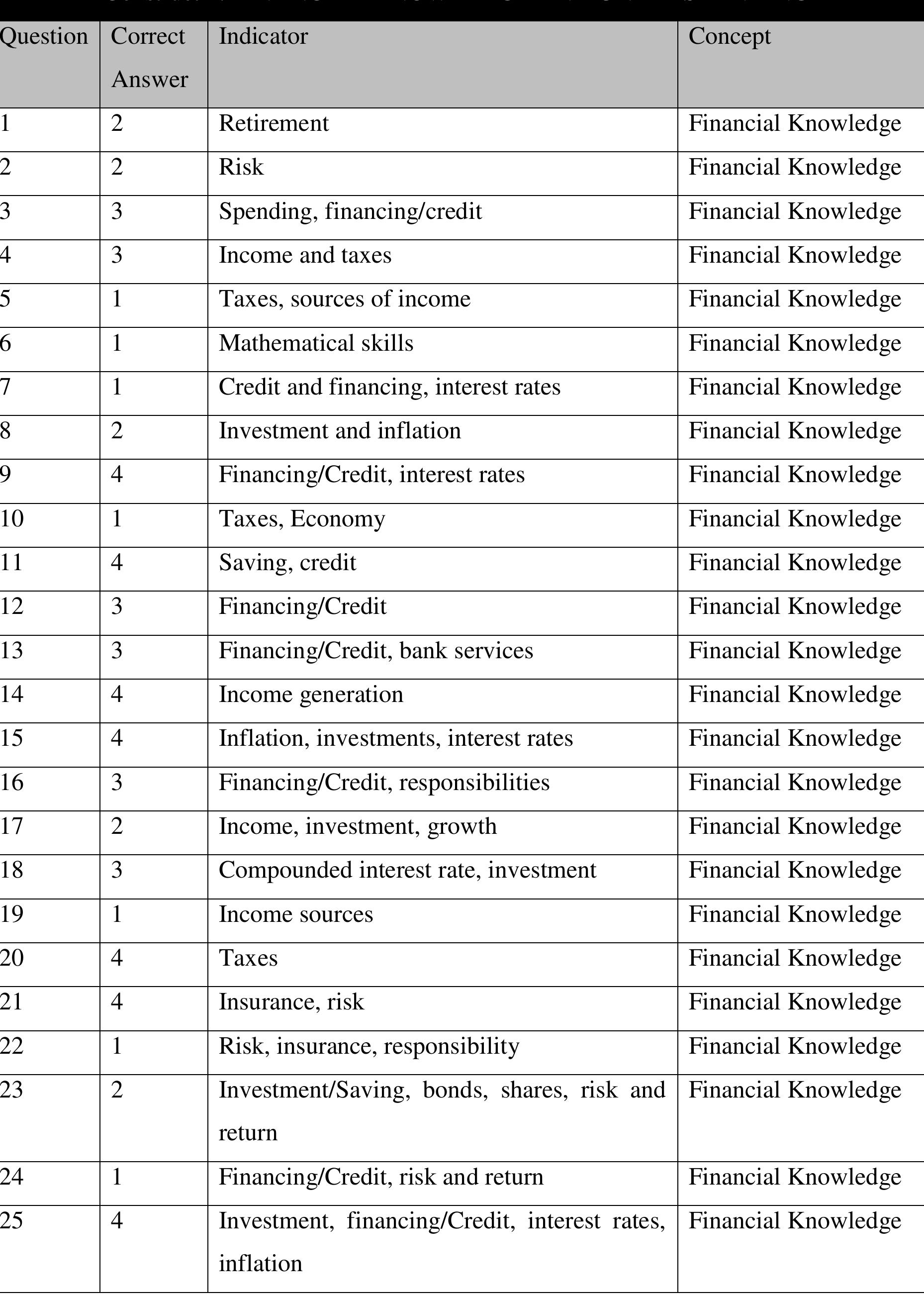

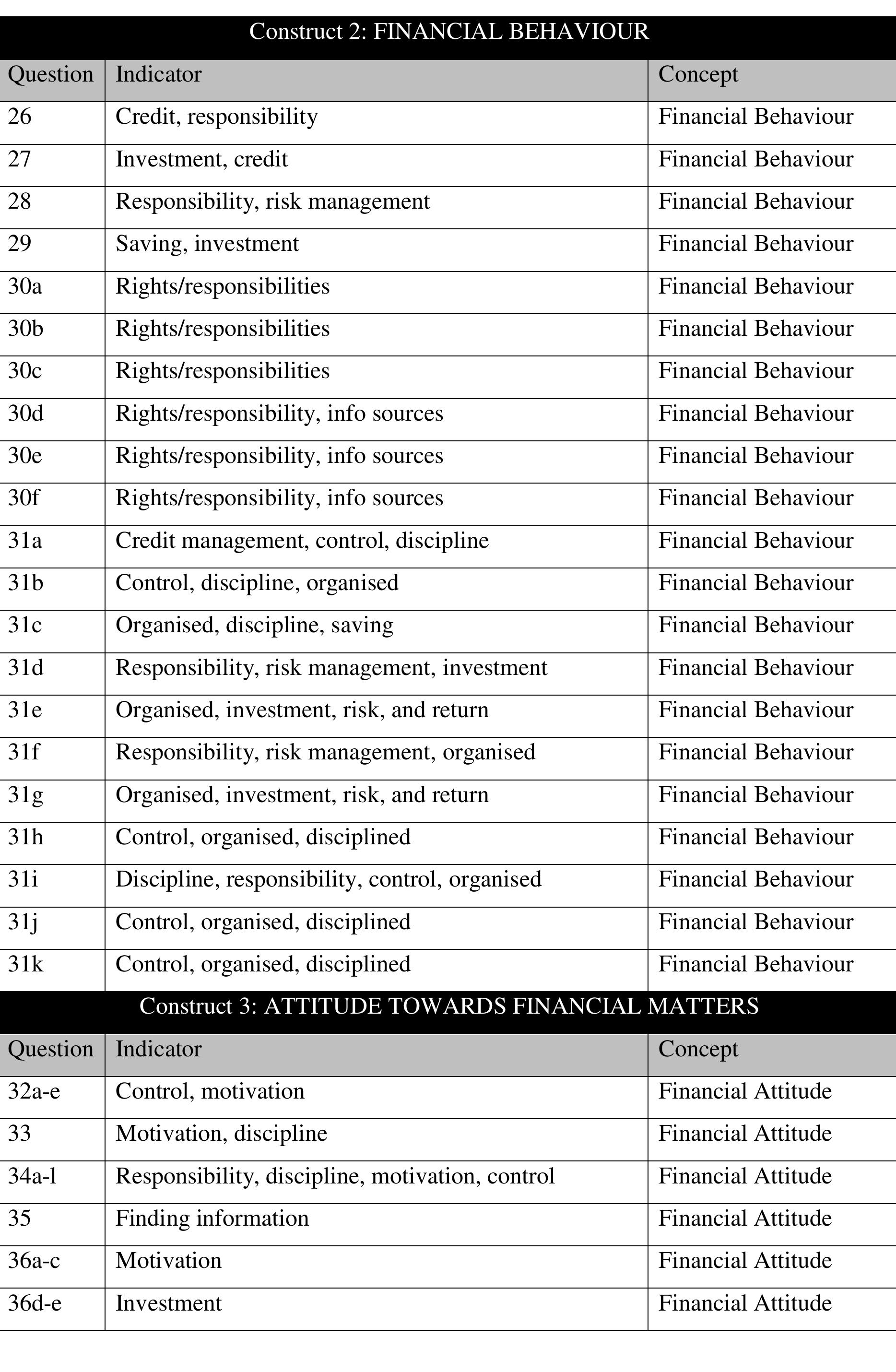

on page 60. Appendix B: Question Matrixon page 68 highlights the questions and what they

indicate within each financial literacy construct. It also points out the correct answers for the

financial knowledge and understanding construct.

Convenience sampling was followed for the present study. Convenience sampling falls under a

non-probability sampling method. A non-probability sampling method occurs in situations

where the sampling techniques or elements do not have a known or predetermined chance of

being selected as subjects (Sekaran, 2001). Convenience sampling allows the researcher to

collect information from the population who are most conveniently available, although they are

to fall under the criteria relevant to the study (Sekaran, 2001).

4.5 POPULATION AND SAMPLE SIZE

The sample size was made up of 32 participants. The researcher approached crypto-user

communities through cryptocurrency forums, social media and trading platforms where

electronic questionnaires were sent to the research participants. The approach followed a non-

probability, convenience-sampling technique as participants were selected because of their

convenient accessibility by the researcher.

4.6 DATA ANALYSES

The data was analysed by means of descriptive statistics to access the level of financial literacy

among cryptocurrency users in terms of the financial literacy constructs. In order to assess the

Page 30 of 74

�reliability and the validity of the measurement instrument, an item analysis will be completed

on the elements of the financial literacy instrument.

The primary data of each respondent was collated through the online questionnaire system

application and exported to a statistics program. In order to ensure that all the questions in the

questionnaires are completed, the online questionnaire was formatted to make each

field/question required to ensure that only completed questionnaires were included in the

analysis.

4.7 RELIABILITY AND VALIDITY

To ascertain the reliability and internal consistency of the data collected, Cronbach’s Alpha was

calculated. Cronbach’s Alpha ranges between 0 and 1, with 0 indicating a perfectly unreliable

measurement and 1 being a perfectly reliable measurement (George and Mallery, 2003). The

Cronbach Alpha was calculated for each personal financial literacy construct in the

questionnaire to measure the reliability of the instrument.

van Nieuwenhuyzen’s (2009) study indicated that the measurement tool developed for the study

had a Cronbach Alpha score of 0.70 for the financial knowledge section, a Cronbach Alpha

score of 0.79 for the financial behaviour section, and a Cronbach Alpha score range from 0.6

to 0.83 for questions relating to attitudes towards financial matters. The scores suggest high

levels of reliability and internal consistency of the complete instrument.

4.8 ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS

This research was in accordance with the ethical requirements set out by the Rhodes University

Human Ethics Committee protocol. All ethical considerations regarding informed consent,

voluntary participation, non-disclosure, confidentiality, use of the research data and storage of

the data will be adhered to throughout the study.

Before the actual questionnaire was accessed, participants were approached by means of a

public notice (Appendix C: Public Notice on page 70) posted on the cryptocurrency forums,

social media, and trading platforms. The link to the survey formed part of the public notice.

Participants clicked on the link to access the individual participation (Appendix D: on page 71)

and informed consent notice (Appendix E: Informed Consent Notice on page 72).

Page 31 of 74

�4.9 SUMMARY

This section concentrated on the exploration plan and system of the present investigation. The

examination reasoning and goals were illustrated and depicted. From that point, the exploration

ideal models utilised in the present research was recognised. Research techniques utilised were

then analysed and along these lines, the review strategy, which was utilised in this investigation,

was touched on in detail including the unwavering quality and legitimacy of the instruments of

past examinations adjusted for this exploration study. Additionally, the selection of the sample

group had been outlined. Furthermore, information examination systems were analysed in

detail. In conclusion, moral contemplations which the analyst guaranteed would be set up in

this examination were clarified.

The results of the data collected will be presented in the next Chapter.

Page 32 of 74

�CHAPTER FIVE: DATA ANALYSIS AND RESULTS

5.1 INTRODUCTION

The past section gave explicit information around the research methodology of the present

investigation which laid out the motivation behind the exploration, points, and goals. The

following chapter part provides details regarding the information examination and the

experimental discoveries of this investigation. All the more explicitly, the principle reason for

this part is to display the results to the objectives outlined in Chapters One and Chapters Four.

Accordingly, exact discoveries from the descriptive statistics are exhibited.

5.2 DEMOGRAPHICS

This section describes the descriptive findings for the demographic variables included in the

study as indicated in Figure 1 to Figure 4. Variables include gender, age, nationality and highest

qualification obtained by participants. A detailed description of each variable is given.

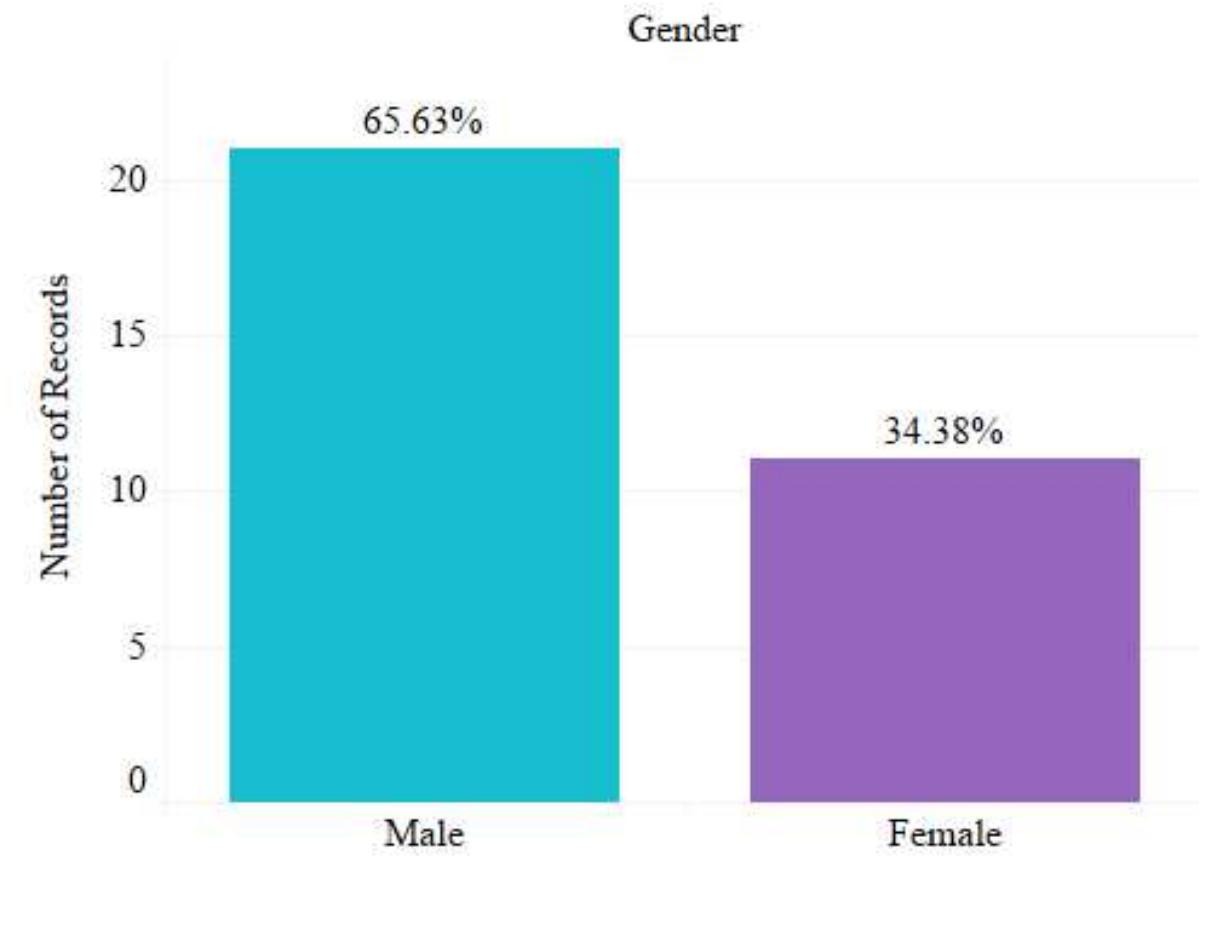

Gender

Figure 1 below outlines the sum of the number of records within each gender category. The

categories are colour coded and the markings a labelled by the percentage of the Total Number

of Records. From Figure 1, it is made apparent that the majority of the participants were male,

consisting of 21 respondents (65.63%) while female participants comprised 11 respondents

(34.38%).

Figure 1: Gender of Participants

Page 33 of 74

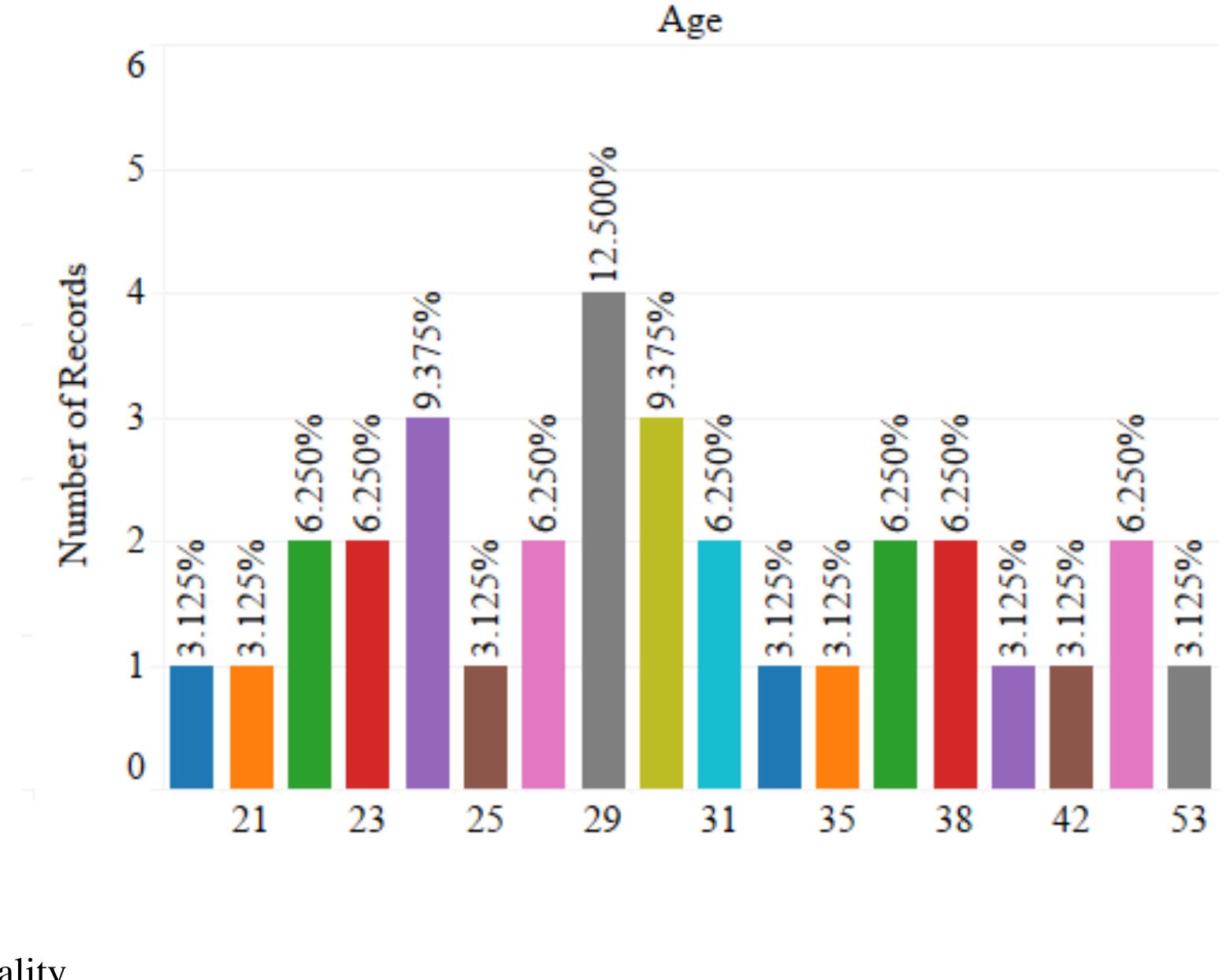

�Age

As seen from Figure 2 below, the greater part of respondents was 29 years old and consisted of

4 respondents (12.5%). In totality, the majority of participants were below the age of 30 years

old (46.88%). This is followed by 11 participants (34.38%) in their 30s.

Figure 2: Age of Participants

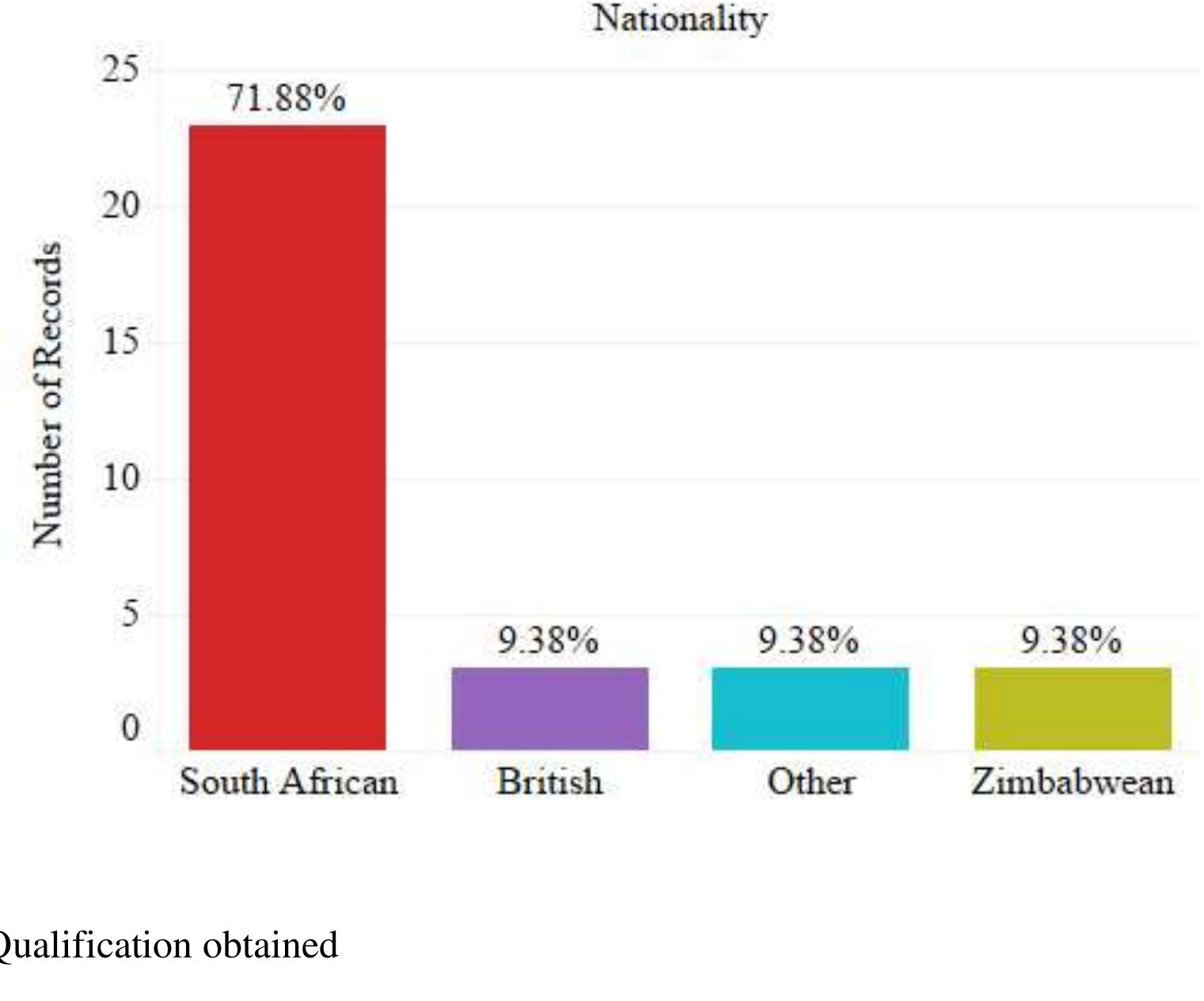

Nationality

The following bar graph (Figure 3 on page 35) illustrates that the majority of the respondents

were of South African nationality, which encompassed 23 participants (71.88%). The

remaining respondents comprised of 3 British respondents (9.38%), and 3 respondents (9.38%)

from Zimbabwean nationality. The “Other” group comprised of 3 (9.38%) respondents and

were made up of 1 participant of Djiboutian, Australian and Indian decent.

Page 34 of 74

�Figure 3: Nationality of Participants

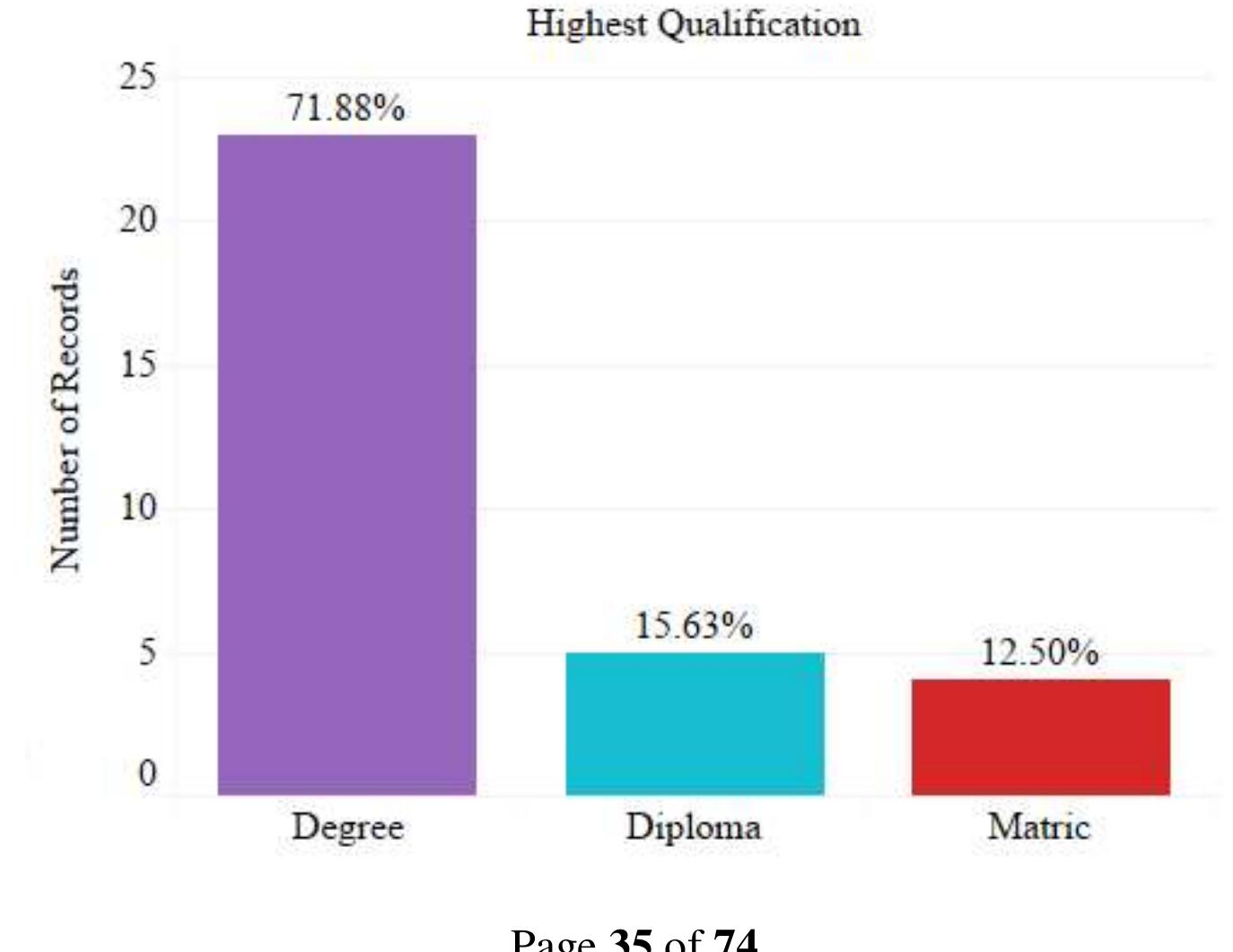

Highest Qualification obtained

The following bar graph (Figure 4 below) illustrates that the majority of the respondents had

obtained degrees, which comprised of 23 respondents (71.88%). 5 respondents (15.63%) had

diplomas and 4 participants (12.50%) only had a Matric certificate.

Figure 4: Highest Qualification obtained by Participants

Page 35 of 74

�5.3 USER DATA

The following section highlights the descriptive findings for the data collection variables about

what kind of cryptocurrency user the participants were. This draws attention to whether a

participant, in fact, purchases cryptocurrencies, uses cryptocurrencies to purchase goods and

services, mines cryptocurrencies and/or trades cryptocurrencies. The data takes note of which

cryptocurrency is purchased and, in addition, if a user trades cryptocurrency, the platforms they

used were determined.

From Figure 5 below, of the 32 participants, all 32 participants (100%) purchase

cryptocurrencies. This question was used as a filter to be able to clean the data from participants

who were not part of the sample group. Figure 5 below shows that there was no need for any of

the participant records to be deleted from the data.

Figure 5: How many users Purchase Cryptocurrencies

There were 20 participants (62.50%) who use cryptocurrencies to purchase goods and services

but 12 participants (37.50%) stated they do not utilise cryptocurrencies in that manner. This can

be seen in Figure 6 below.

Figure 6: How many users utilise Cryptocurrencies to Purchase Goods and Services

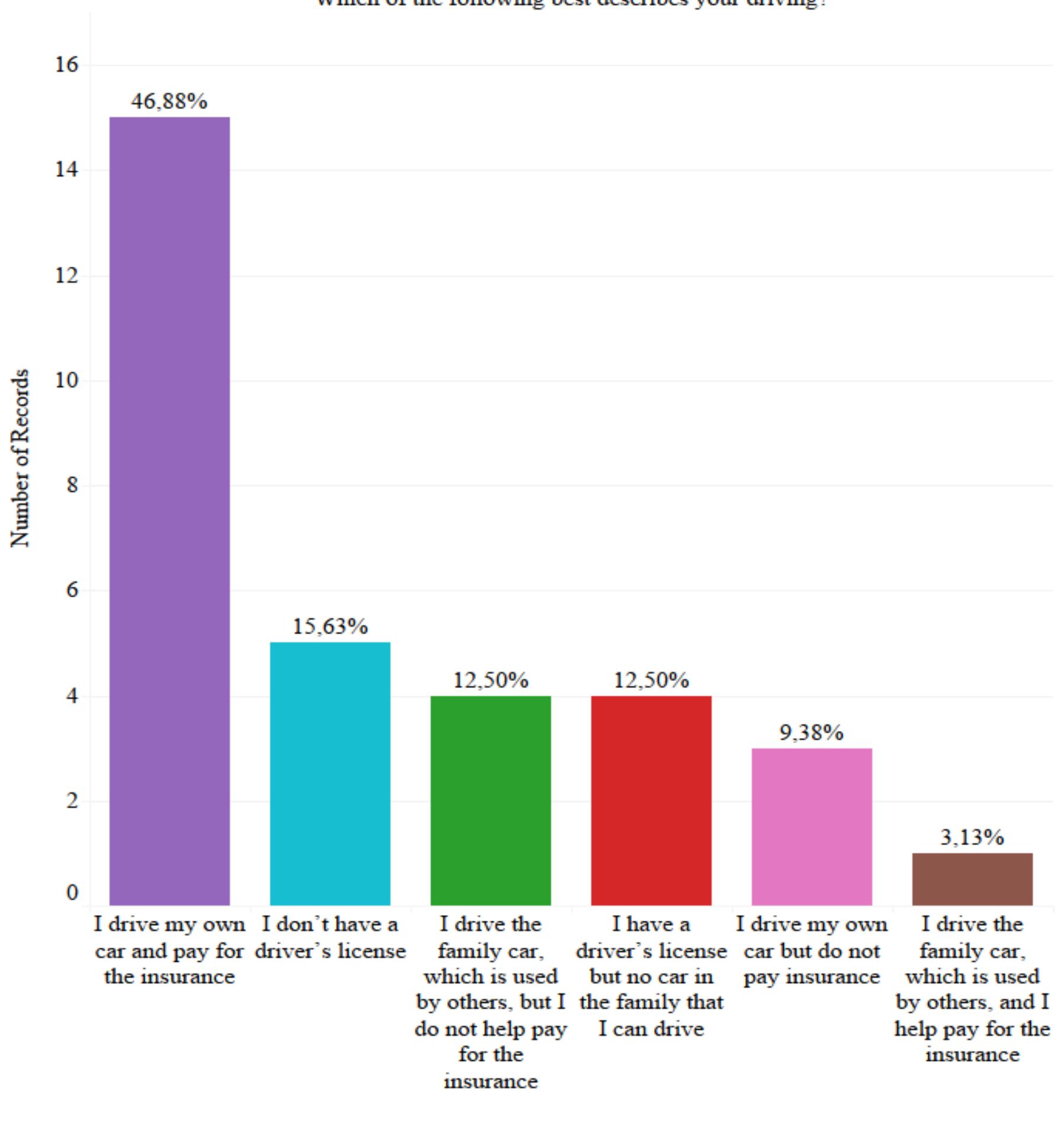

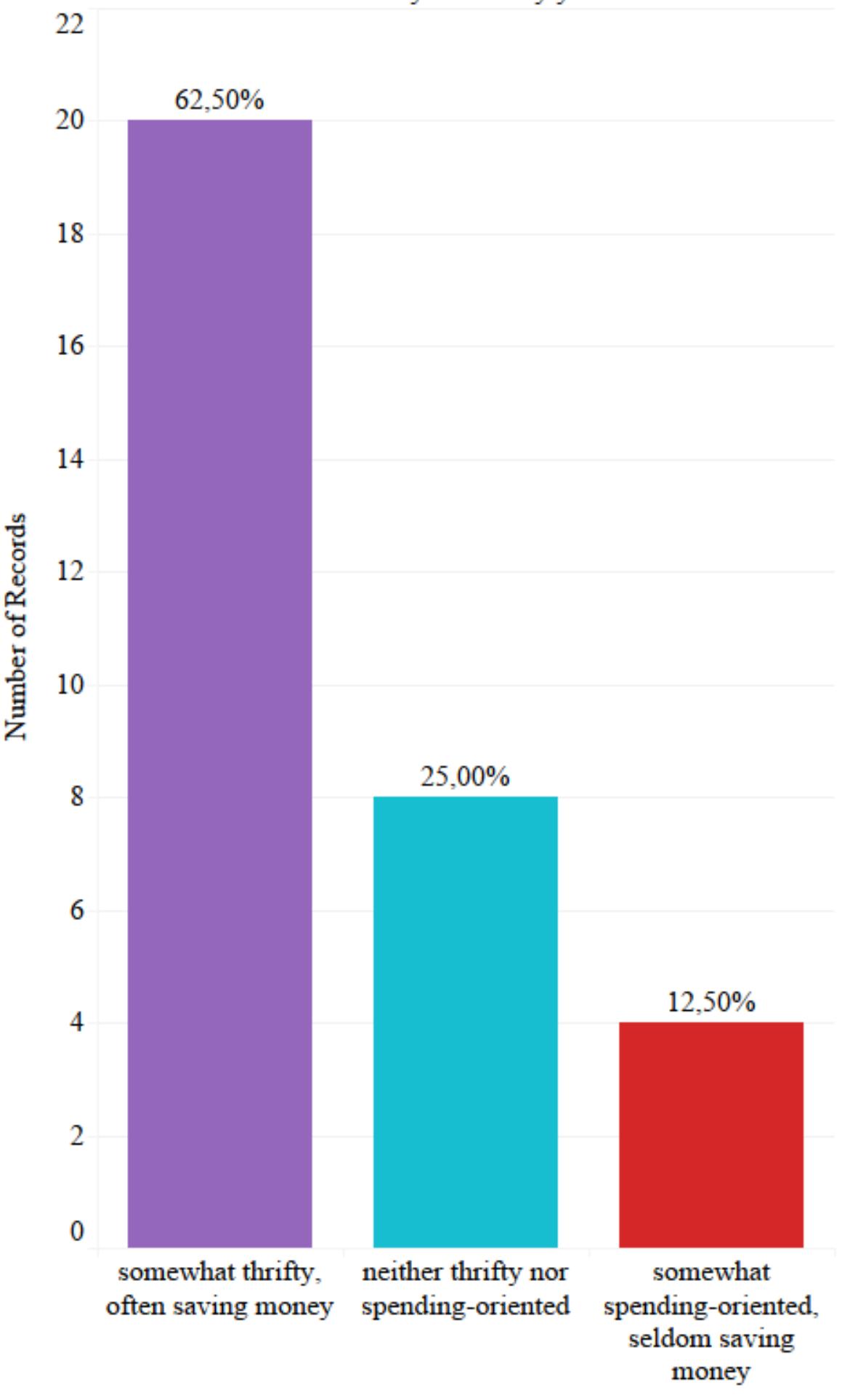

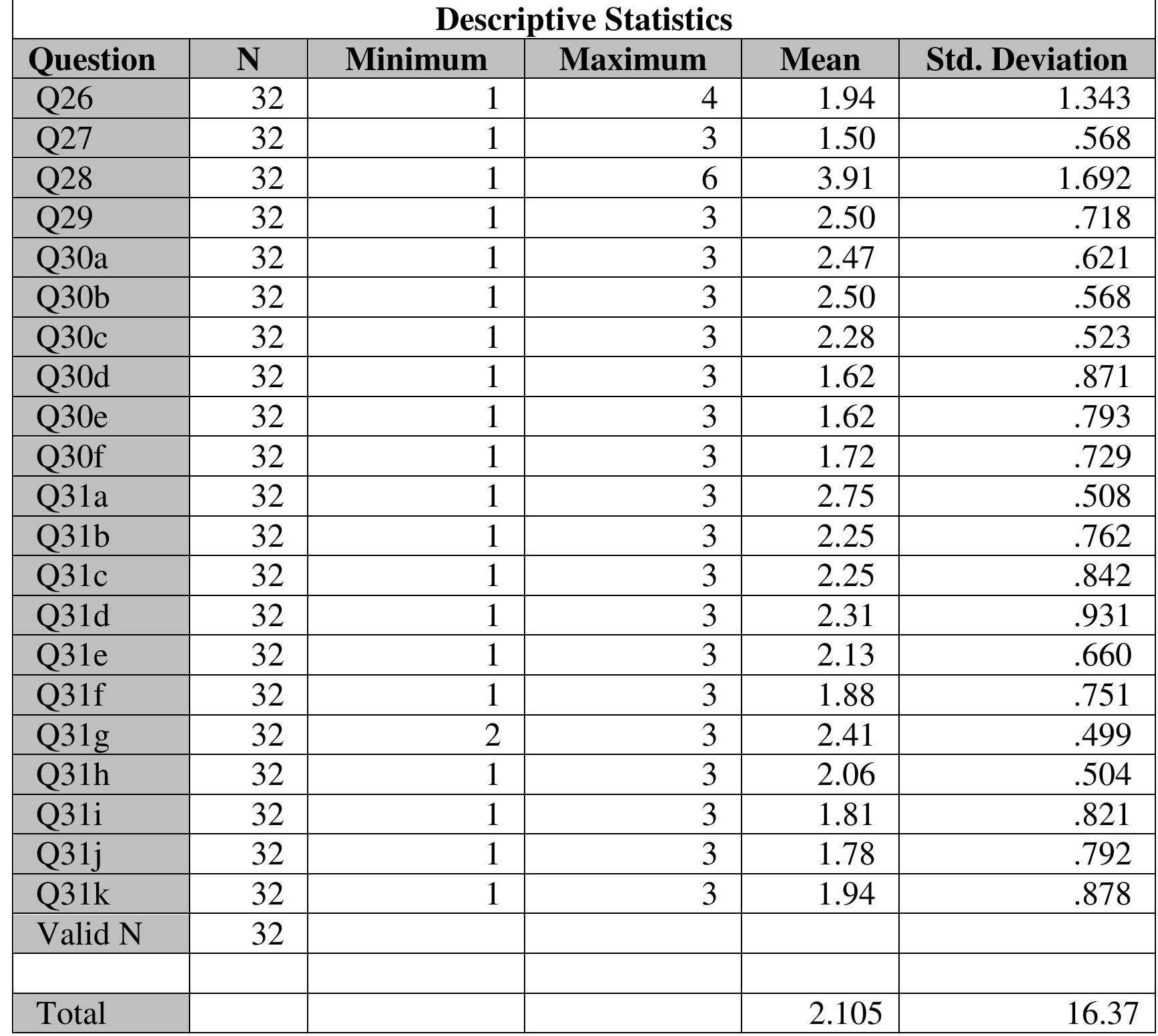

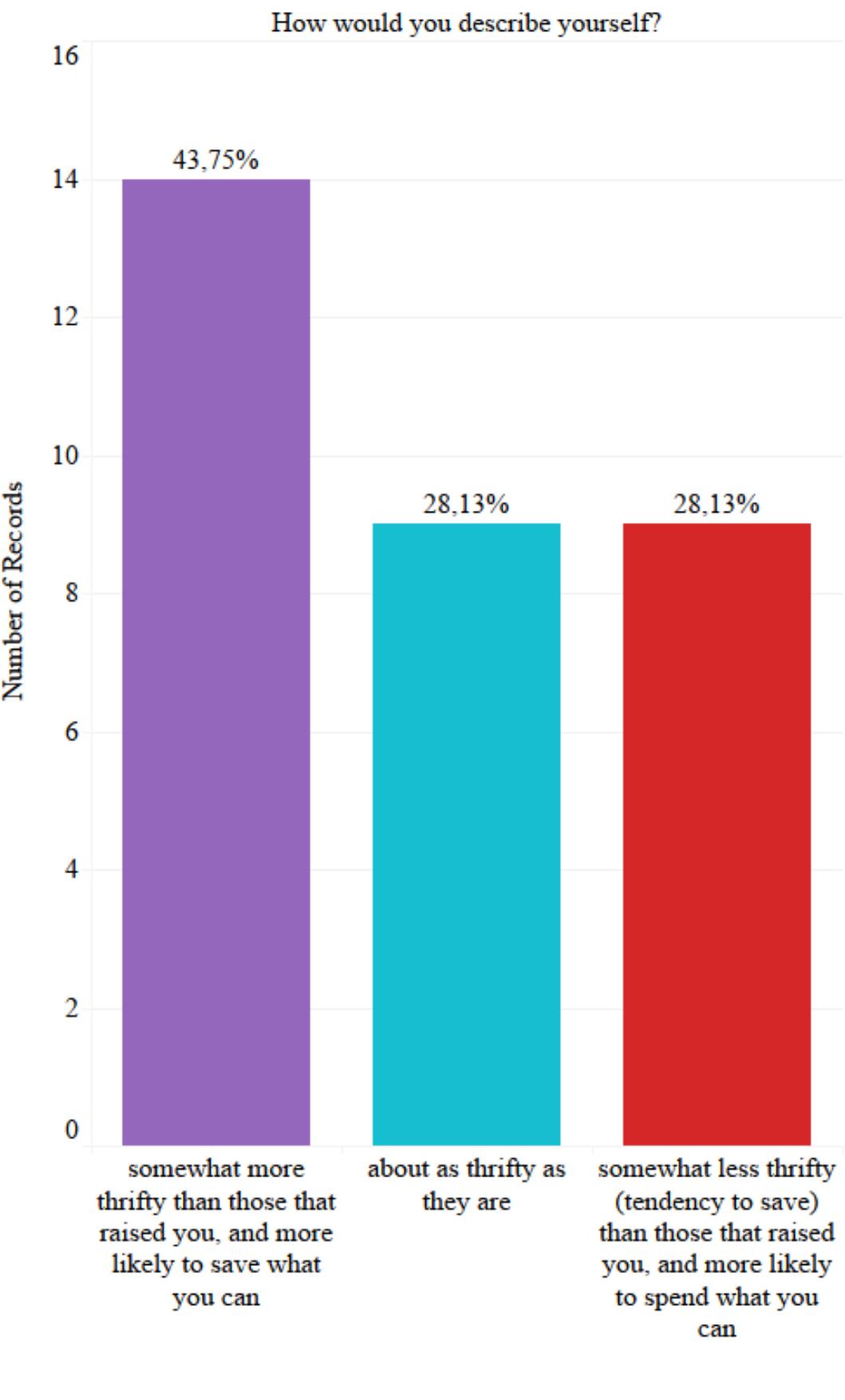

Page 36 of 74