Twenty-one years ago, the U.S. and its allies invaded Iraq in the erroneous belief that the country possessed weapons of mass destruction and was allied with al-Qaida, the terror group responsible for the 9/11 attacks.

The U.S. created an occupation authority, but failed to restore order and helped spawn the insurgency that bedeviled it by dismissing the entire Iraqi military and the most experienced civil servants. Coalition troops fought a losing battle, regained their footing with the 2007 troop surge, and finally departed in 2011. U.S. troops returned in 2014 to fight the Islamic State and they remain there to this day, though ISIS was largely eliminated by 2019.

In January 2020, Iraq’s parliament voted on a nonbinding measure to remove the U.S. troops from Iraq, but the Americans remain at the request of the Iraqi government. However, in response to the parliament’s 2020 vote, Iraq and the International Coalition changed the mission of the troops from a combat mission to one of advisory and training.

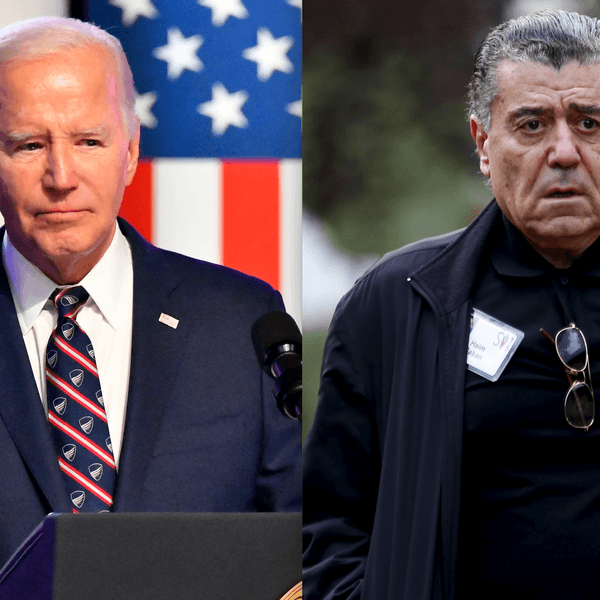

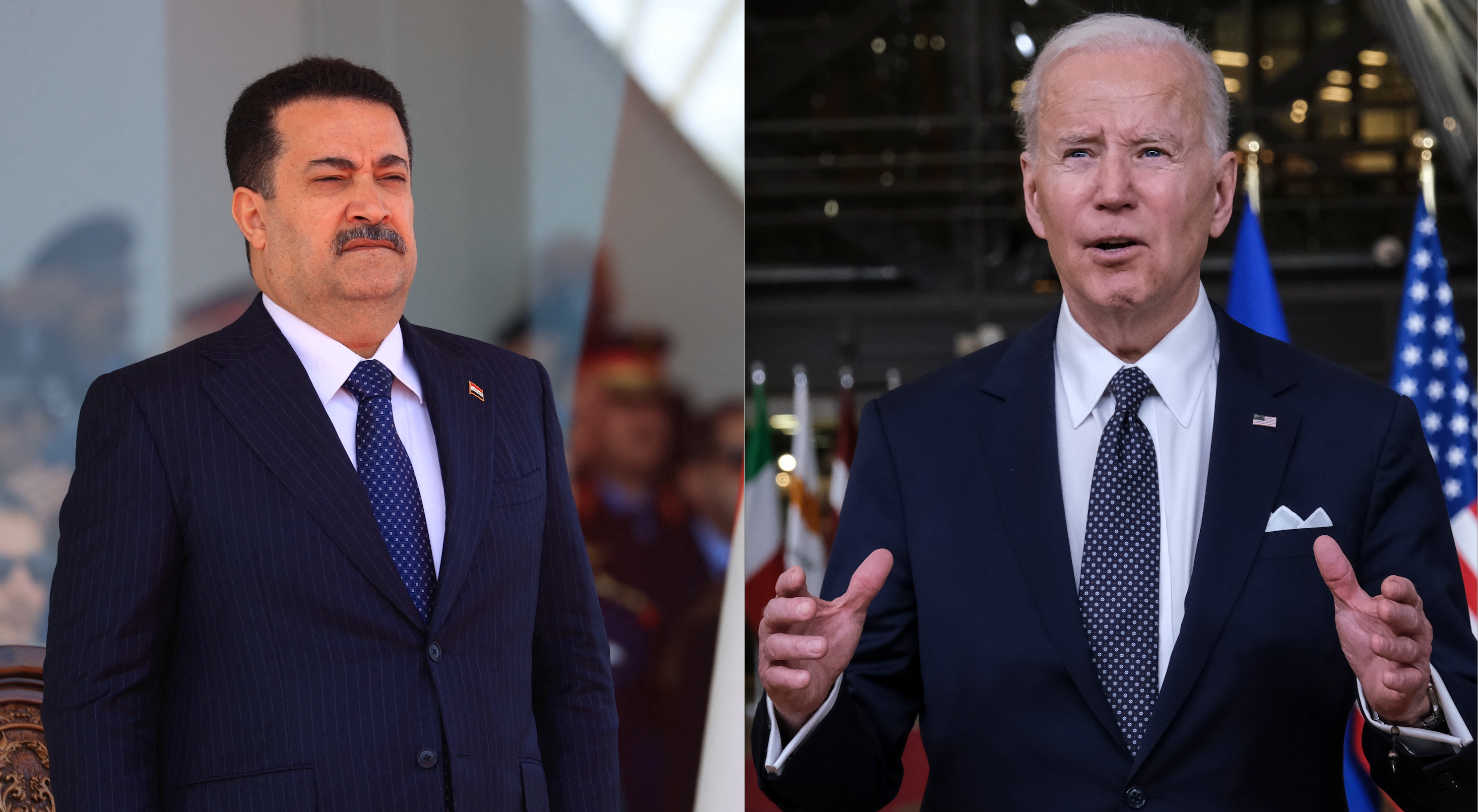

Iraq’s prime minister, Mohammed Shia' Al Sudani, will meet U.S. President Joe Biden on April 15, primarily to discuss the U.S. troop presence.

Though the U.S.-Iraq Higher Military Commission is reviewing the troop presence issue, will the U.S. side stall fearing it may have to agree to a smaller presence and constrained operations? Possibly, so Sudani may want a public commitment from Biden to force the march to a constructive, timely decision.

Aside from the troops issue, Sudani wants to strengthen Baghdad’s ties with Washington, which he considers Iraq’s top bilateral relationship, and to add an economic dimension to Iraq’s ties with America.

When Americans think of Iraq in economic terms it’s all about the oil, but in November 2023 ExxonMobil, America’s biggest oil company, exited Iraq with nothing to show for a decade-long effort. The departure will lower the expectation of other U.S. companies, but Sudani wants to revitalize economic ties, and he will be accompanied by many of the country’s top businessmen.

U.S.-Iraq trade has room for growth. In 2022, the U.S. exported $897 million in goods, the top product being automobiles. Iraq, in turn, exported $10.3 billion in goods, most of it crude oil.

A key economic objective of Iraq is the $17 billion Development Road, an overland road and rail link from the Persian Gulf to Europe via Turkey, that will host free-trade zones along its length.

Biden and Sudani should consider the shape of the future U.S.-Iraq relationship, which has to now been governed by military considerations, and has become the best example of The Meddler’s Trap, “a situation of self-entanglement, whereby a leader inadvertently creates a problem through military intervention, feels they can solve it, and values solving the new problem more because of the initial intervention. …A military intervention causes a feeling of ownership of the foreign territory, triggering the endowment effect.”

Iraq is the only real democracy in the Arab world, and many young Iraqis want a separation of religion and state, something that should resonate with Americans and, Iraqis hope, cause the U.S. to deal with Iraq as Iraq, not a platform for operations against Syria and Iran, or to support Washington’s Kurdish clients.

Washington damaged itself in Iraq by killing Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF) leader Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis in January 2020. Baghdad had moved the PMF, once a militia, into the government in 2016 (no doubt with American encouragement), so the killing of Muhandis, then a government official, increased popular support the PMF.

What are some clouds on the horizon for the U.S. and Iraq?

Corruption. Pervasive corruption in Iraq has slowed economic development and subjected Iraqi citizens to ineffective governance. The 2023 Corruption Perceptions Index by Transparency International ranked Iraq 154 of 180, a slight improvement from 2022 when it ranked 157 of 180.

Iraq was previously described by TI as: “Among the worst countries on corruption and governance indicators, with corruption risks exacerbated by lack of experience in the public administration, weak capacity to absorb the influx of aid money, sectarian issues and lack of political will for anti-corruption efforts.”

Sudani has not ignored corruption, calling it one of the country’s greatest challenges and “no less serious than the threat of terrorism.”

Elizabeth Tsurkov. Tsurkov is a Russian-Israeli academic who was kidnapped in 2023 by Kata’ib Hezbollah, an Iranian-influenced Iraqi militia. Tsurkov, a doctoral student at Princeton University in the U.S., entered Iraq with her Russian passport and did not disclose that she was an Israeli citizen and Israeli Defense Forces veteran. (A 2022 Iraqi law criminalized any relations with Israel.)

Tsurkov’s family wants the Biden administration to designate Iraq a state sponsor of terrorism for failing to secure her release. Sudani’s office announced an investigation into the matter and the issue may arise when Sudani meets Biden, though the best outcome for Iraq and the U.S. is a Russia-brokered deal between Israel and Iran.

If Biden designates Iraq a state sponsor of terrorism that will irreparably damage the relationship and open the door for China.

China. The U.S. is Iraq’s top relationship, but not its only relationship. China will respond to the ostracism of Baghdad by extending invitations to the Shanghai Cooperation Organization and BRICS, the latter of which can fund infrastructure projects through the New Development Bank. PetroChina replaced ExxonMobil in West Qurna 1, one of Iraq’s biggest oil fields, and is ideally positioned for further expansion. And Iraq was the “leading beneficiary” of China’s Belt and Road Initiative investment in 2021.

Sudani has said Iraq should not be a cockpit of conflict for the U.S, and Iran, but when Iran is concerned it, in Washington, is always 1979. Though Sudani has many challenges to face, Biden has more: he must reorient his government away from its colonial mentality in West Asia, recognize that Baghdad must reach a modus vivendi with Tehran that may not be to Washington’s pleasure, and not smooth the way for Beijing’s greater penetration of West Asia.

- Iraq can't hold off Gaza's spillover much longer ›

- Iraqis: Don't use our country as a 'proxy battleground' ›

- The new Iraqi PM is a status quo leader, but for how long? ›

![Following a largely preordained election, Vladimir Putin was sworn in last week for another six-year term as president of Russia. Putin’s victory has, of course, been met with accusations of fraud and political interference, factors that help explain his 87.3% vote share. If this continuation of Putin’s 24-year-long hold on power makes one thing clear, it’s that he and his regime will not be going anywhere for the foreseeable future. But, as his war in Ukraine continues with no clear end in sight, what is less clear is how Washington plans to deal with this reality. Experts say Washington needs to start projecting a long-term strategy toward Russia and its war in Ukraine, wielding its political leverage to apply pressure on Putin and push for more diplomacy aimed at ending the conflict. Only by looking beyond short-term solutions can Washington realistically move the needle in Ukraine. Since Russia’s full-scale invasion, the U.S. has focused on getting aid to Ukraine to help it win back all of its pre-2014 territory, a goal complicated by Kyiv’s systemic shortages of munitions and manpower. But that response neglects a more strategic approach to the war, according to Andrew Weiss of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, who spoke in a recent panel hosted by Carnegie. “There is a vortex of emergency planning that people have been, unfortunately, sucked into for the better part of two years since the intelligence first arrived in the fall of 2021,” Weiss said. “And so the urgent crowds out the strategic.” Historian Stephen Kotkin, for his part, says preserving Ukraine’s sovereignty is critical. However, the apparent focus on regaining territory, pushed by the U.S., is misguided. “Wars are never about regaining territory. It's about the capacity to fight and the will to fight. And if Russia has the capacity to fight and Ukraine takes back territory, Russia won't stop fighting,” Kotkin said in a podcast on the Wall Street Journal. And it appears Russia does have the capacity. The number of troops and weapons at Russia’s disposal far exceeds Ukraine’s, and Russian leaders spend twice as much on defense as their Ukrainian counterparts. Ukraine will need a continuous supply of aid from the West to continue to match up to Russia. And while aid to Ukraine is important, Kotkin says, so is a clear plan for determining the preferred outcome of the war. The U.S. may be better served by using the significant political leverage it has over Russia to shape a long-term outcome in its favor. George Beebe of the Quincy Institute, which publishes Responsible Statecraft, says that Russia’s primary concerns and interests do not end with Ukraine. Moscow is fundamentally concerned about the NATO alliance and the threat it may pose to Russian internal stability. Negotiations and dialogue about the bounds and limits of NATO and Russia’s powers, therefore, are critical to the broader conflict. This is a process that is not possible without the U.S. and Europe. “That means by definition, we have some leverage,” Beebe says. To this point, Kotkin says the strength of the U.S. and its allies lies in their political influence — where they are much more powerful than Russia — rather than on the battlefield. Leveraging this influence will be a necessary tool in reaching an agreement that is favorable to the West’s interests, “one that protects the United States, protects its allies in Europe, that preserves an independent Ukraine, but also respects Russia's core security interests there.” In Kotkin’s view, this would mean pushing for an armistice that ends the fighting on the ground and preserves Ukrainian sovereignty, meaning not legally acknowledging Russia’s possession of the territory they have taken during the war. Then, negotiations can proceed. Beebe adds that a treaty on how conventional forces can be used in Europe will be important, one that establishes limits on where and how militaries can be deployed. “[Russia] need[s] some understanding with the West about what we're all going to agree to rule out in terms of interference in the other's domestic affairs,” Beebe said. Critical to these objectives is dialogue with Putin, which Beebe says Washington has not done enough to facilitate. U.S. officials have stated publicly that they do not plan to meet with Putin. The U.S. rejected Putin’s most statements of his willingness to negotiate, which he expressed in an interview with Tucker Carlson in February, citing skepticism that Putin has any genuine intentions of ending the war. “Despite Mr. Putin’s words, we have seen no actions to indicate he is interested in ending this war. If he was, he would pull back his forces and stop his ceaseless attacks on Ukraine,” a spokesperson for the White House’s National Security Council said in response. But neither side has been open to serious communication. Biden and Putin haven’t met to engage in meaningful talks about the war since it began, their last meeting taking place before the war began in the summer of 2021 in Geneva. Weiss says the U.S. should make it clear that those lines of communication are open. “Any strategy that involves diplomatic outreach also has to be sort of undergirded by serious resolve and a sense that we're not we're not going anywhere,” Weiss said. An end to the war will be critical to long-term global stability. Russia will remain a significant player on the world stage, Beebe explains, considering it is the world’s largest nuclear power and a leading energy producer. It is therefore ultimately in the U.S. and Europe’s interests to reach a relationship “that combines competitive and cooperative elements, and where we find a way to manage our differences and make sure that they don't spiral into very dangerous military confrontation,” he says. As two major global superpowers, the U.S. and Russia need to find a way to share the world. Only genuine, long-term planning can ensure that Washington will be able to shape that future in its best interests.](https://responsiblestatecraft.org/media-library/following-a-largely-preordained-election-vladimir-putin-was-sworn-in-last-week-for-another-six-year-term-as-president-of-russia.jpg?id=34283894&width=1245&height=700&quality=90&coordinates=0%2C77%2C0%2C77)