Senate filibuster remains intact after Manchin, Sinema vote with Republicans

Fox News congressional correspondent Chad Pergram reports from Capitol Hill on the fallout.

CAPITOL HILL – When it comes to the filibuster, Sen. Joe Manchin, D-W.Va., pines for the days of Sen. Strom Thurmond, R-S.C., Jimmy Stewart and "Mr. Smith Goes to Washington." Even the likes of Sens. Rand Paul, R-Ky., and Chris Murphy, D-Conn., from a few years back.

"I love the talking filibuster," said Manchin. "I think we should basically be (transparent) in how we do our business here or lack of doing business."

The senators mentioned above, fictitious or not, all executed lengthy filibuster speeches in the Senate. Thurmond holds the record for the longest speech in Senate history: 24 hours and 18 minutes in 1957. However, as Fox News has reported before, Thurmond’s civil rights bill "filibuster" should actually have an asterisk by it. Thurmond abandoned the floor on multiple occasions. He grabbed a sandwich and briefly even allowed the Senate to conduct other business.

A filibuster, by nature, is a dilatory tactic. An effort by a small band of senators - or even just one - to stop the Senate from completing its business. Or, it’s a gambit to stretch things out.

But here are some things to know about what constitutes a filibuster and what falls short. And, some of what people define as a filibuster is in the eyes of the beholder.

A "filibuster" is not limited to a senator dramatically assuming the Senate floor to speak for hours on end. Certainly, seizing the floor for an all-night session and refusing to yield, ala Thurmond or Stewart’s character, Sen. Jefferson Smith, is one way to block the Senate from moving. But, speechifying has its limits. There are bladders. Hoarse voice boxes. Worn insoles. Creaky, trick knees. A speaking filibuster can truly, only last so long.

Sen. Joe Manchin, D-W.Va., on Capitol Hill in October 2021. (AP Photo/J. Scott Applewhite, File)

The word "filibuster" is absent from the U.S. Constitution. You also won’t find the word in the Senate rules. However, Article I, Section 5 of the Constitution permits the House and Senate to make their own rules. Unlike the House, the Senate features "unlimited debate." But, senators may curb such debate under Senate Rule XXII (22). That is the rule which may "bring debate to a close." In essence, stopping all the talking or floor time. If the Senate doesn’t secure 60 yeas, "debate" can conceivably continue, ad infinitum.

Senators are sometimes accused of "filibustering from their offices." Or, "from across town." Or, "from McLean, Va." If the Senate can’t commandeer 60 yeas, "debate" continues.

One could argue that’s in fact a "filibuster."

This is where it gets interesting.

What constitutes "debate" in the Senate?

Certainly, debate is someone on the floor "debating" an issue. But in Senate parlance, "debate" may also mean the Senate is just "on" a bill without anyone talking about it at that minute. This is the "phoning it in" scenario. So why bother to actually block something on the floor?

Over the past several weeks, Manchin discussed a "talking filibuster." Senators have also had conversations about creating a mechanism to compel members to actually talk on the floor. And when they are exhausted, the filibuster is over.

Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer, D-N.Y., at a Senate panel hearing Jan. 5. (Elizabeth Frantz/Pool via AP, File)

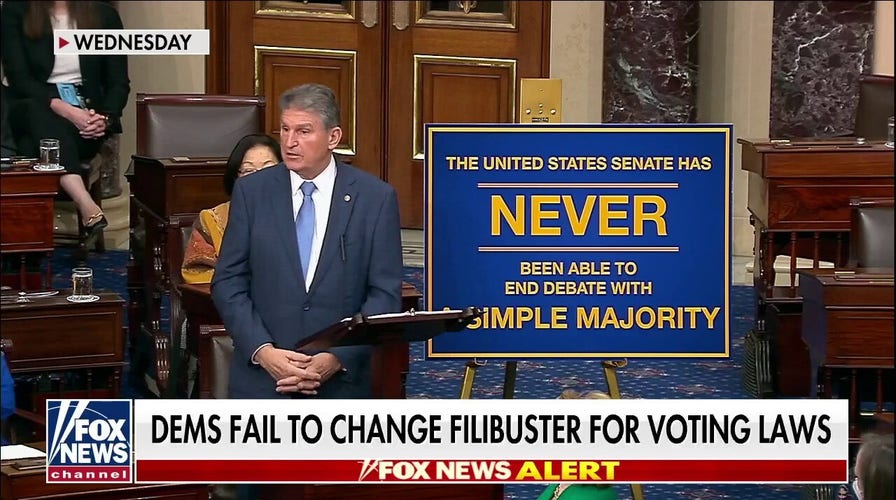

This is why Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer, D-N.Y., even proposed a one-time exception to the filibuster on the voting rights bill this week. He hoped to exploit a loophole to allow senators to talk for as long as they wanted on the floor – even twice – on the issue. Technically senators are only allowed to debate "once" on a given subject. Still, Manchin and Sen. Kyrsten Sinema, D-Ariz., wouldn’t budge on a temporary filibuster alteration.

For nearly 50 years, many filibusters failed to resemble anything reflected in pop culture.

Late Senate Majority Leaders Mike Mansfield, D-Mont., and Robert Byrd, D-W.Va., began "dual tracking" for legislation. By simultaneously juggling multiple issues, senators weren’t actually weighing in on the actual status of a bill on the floor, via talking. If it became apparent there were objections to concluding, the leaders may "file cloture" (the method to close debate, under Rule XXII) to actually terminate a "phoned-in" filibuster. However, leaders now routinely file cloture on nearly every controversial bill. The modern Senate now votes constantly to end filibusters.

The late Sen. Robert C. Byrd, D-W.Va., during a ceremony at the U.S. Capitol honoring him for his contributions to education. (Scott J. Ferrell/Congressional Quarterly/Getty Images, File)

But, there are very few "talking" filibusters.

DEMS' ‘NUCLEAR OPTION’ PUSH FAILS AFTER MANCHIN, SINEMA VOTE TO KEEP FILIBUSTER

People sometimes perceive the term "filibuster" as pejorative. Those upset by a senator delaying Senate business may claim that they are "filibustering" the legislation. On the other hand, a senator who believes it’s good politics to serve as a roadblock on a particular bill may be happy to embrace the "filibuster" tag. However, if a senator suspects their opponents are unfairly tarring them for "filibustering," they have a convenient defense. A senator may simply state that they aren’t engaged in a filibuster. They are merely exercising their senatorial privileges.

This brings us to an intriguing question about the quintessence of the filibuster. If it’s supposed to be an exercise in logorrhea, aren’t all long speeches filibusters? And, how effective is a speaking filibuster - if it’s nothing more than a delaying tactic? After all, the record is only a little more than 24 hours. All speeches must come to an end.

In September 2013, Sen. Ted Cruz, R-Texas, commanded the floor for 21 hours and 14 minutes in an effort to defund ObamaCare. But before Cruz started to speak, the Senate was on autopilot. Senators voted, 100-0, to start debate on the government funding bill the next day. The Senate had locked in a debate time of 1 p.m.

SCHUMER, DEMS ACCEPT FILIBUSTER FLOOR FAILURE TO FIGHT 'THE GOOD FIGHT’ BEFORE MIDTERMS

Cruz took the floor and spoke for most of the time in between. Cruz may have delivered a marathon speech – including a riff on "Green Eggs and Ham." But the Texas Republican truly didn’t block anything. The Senate was already committed to something the next day. Cruz was just filling the void.

A really long speech? Yes. But technically, not a filibuster.

This raises another issue. Under current Senate constructs, it’s nearly impossible to enforce senators to talk if they want to filibuster. There are certainly ways to end "phoned-in" filibusters. That’s a cloture vote to end debate. Exhaustion will address protracted speeches which are filibusters. But there’s not a method to mandate a senator head to the floor and talk if they insist on delaying legislation.

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

This is the question which vexes the Senate.

And, what vexes the public is the definition of a filibuster – despite what everyone was taught in school about Strom Thurmond and Jimmy Stewart.